First of all, we should look at what information was available about the Minoan civilization in history. In written form there was only the mention in Homer, about the hundred cities of Crete of the famous king Minos. But Homer was 800 years away from the time before the destruction of the palaces in Crete!

There were also traditions related to religion, to Zeus born and raised in the mountains of Crete, to King Minos, the Labyrinth, the Minotaur, Knossos, etc., which were revisited by many writers from ancient times to the Middle Ages and until the end of the 19th century.

But also in Crete there were traditions about places, toponyms and lost states, the sacred caves and mountains, as well as in many areas in the Aegean, in mainland Greece, in the Italian peninsula, in Sicily, there were places with the names "Minoan". All this preserved the myth of a glorious era in Crete, whose elements were dug out of the earth by explorers and conquerors and began to enrich collections and museums.

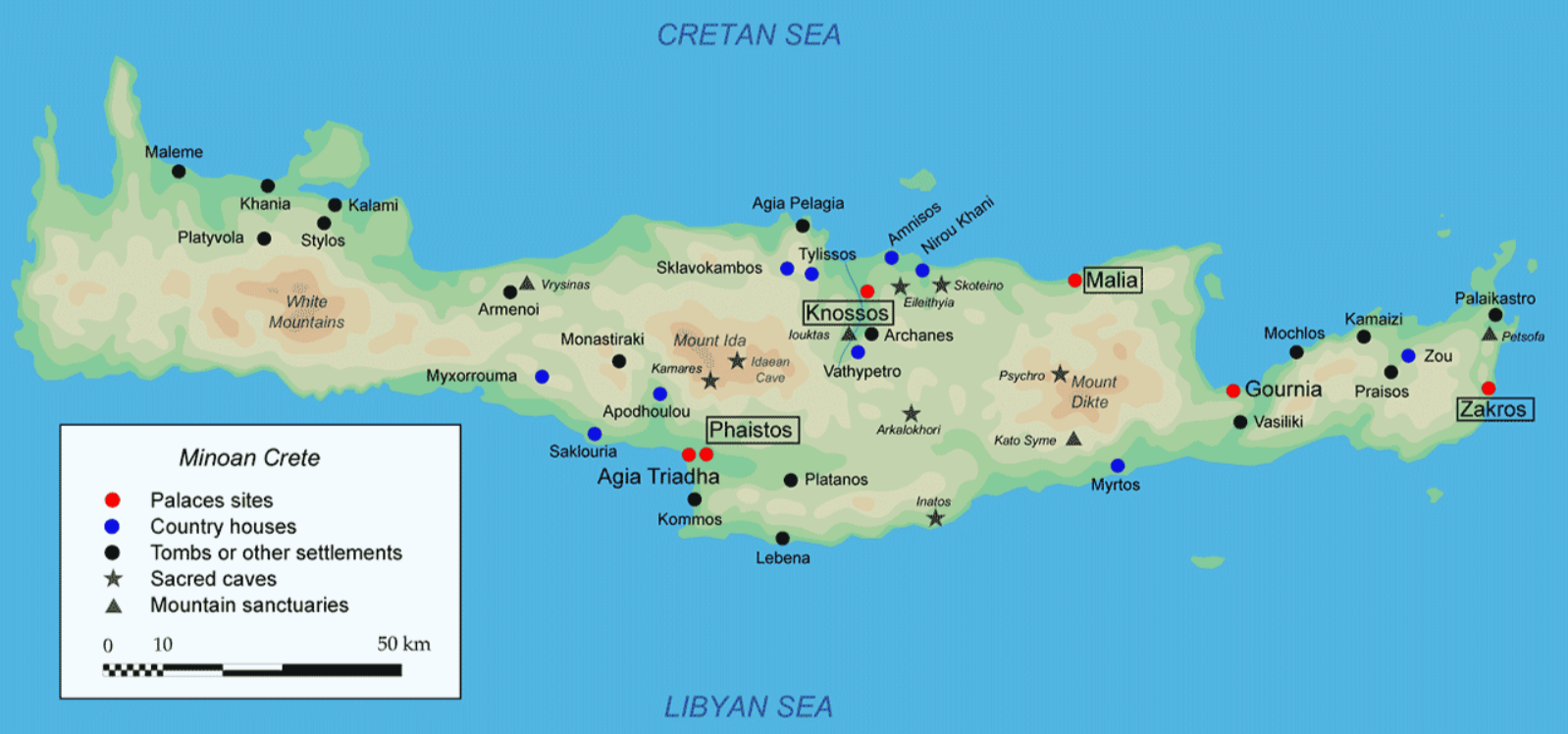

Today we know many things. Systematic excavations have been carried out by distinguished scientific archeologists and the map of Minoan, Mycenaean and Classical Crete has been created.

Specifically for Minoan Crete, we know that the most important cities and palaces are located mainly in central and eastern Crete. As criteria for any activity in Minoan Crete, we must consider the geography, the climate, the distances from the sea or from the plains, and the proximity to other outlying areas with settlements.

Key elements that influenced the choice of the location of a city in Crete were the following:

1. Distance from the coasts. The Mediterranean Sea continued to fill with water after the last ice age and the sea level rose, which meant that people avoided living near the coast at that time.

(Note: According to experts, the level of the Mediterranean Sea drops by up to a hundred meters during the Earth's ice ages, which means that with the end of this period, the sea level gradually rises sharply!)

2. The territory of Crete is located on the borders of the lithospheric plates of Africa and Eurasia and is regularly shaken by large and destructive earthquakes, with the result that, apart from temporary damage, the relief on the coasts changes. In other places there is an uplift and in others a subsidence of the coasts.

3. The geographical relief of Crete, especially with regard to the mountain massifs. The mountains of Crete played an important role in the selection of settlements. The long and narrow Crete has three major mountain massifs from east to west and about ten other smaller ones in between. Originally, the mountains were used as dwellings and places of worship, as there are hundreds of caves where the inhabitants of Crete used to stay (shepherds in winter, refugees in times of war). In some caves there are even churches, which are connected to the ancient sanctuaries. But in ancient times, the caves of Crete were not only inhabited and provided clean water, but were also used as mines, because veins of various metals had been discovered and exploited. So it was a matter of practicality for a city or a settlement to be located near a mountain and caves.

4. The proximity to the great civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean and Egypt, combined with the fact that the activities in Greece and in the West in general were not important according to what we know so far.

Based on the above, the ancient Cretans chose to establish their settlements and cities in mountainous or semi-mountainous areas at altitudes between 200 and 400 meters in the northern part of the island and between 500 and 600 meters on the western and steep side.

The first modern settlers from the 6th or 5th millennium BC, who came from the sea, knew that all invaders would come the same way, and therefore they also avoided the coasts, but also the low plains for settlement. Even today, the villages in Crete are built in places far from the sea, at the roots of the mountains and even hidden from the sight of those who come from the sea (without good intentions).

In general, the rule was: far from the sea, not in a plain, but near a mountain or semi-mountain, near water sources!

But apart from this rule, there was another reason in Crete that influenced the spread of Minoan culture.

This reason was the inhomogeneity of the population between eastern and western Crete, combined with the geographical relief, with the consequence that the important cultural centers developed mainly in the central and eastern parts of the island, since it is very likely that the arrival of people and ideas in Crete was from the east.

Another important feature that influenced the development of people's activities in Crete over time is the climatic conditions. There is a significant difference in climate between eastern and western Crete. Due to the much higher amount of precipitation in western Crete, it is believed that the mountains there were green and very densely forested in ancient times, unlike eastern Crete, where the climate was drier and less humid.

From this it can be seen that the activities of the Minoans in eastern and central Crete are becoming more and more important.

However, systematic and careful excavations were not carried out at all of these sites. On the contrary, since ancient times and perhaps until recently, illegal excavations and looting were carried out in tombs, settlements, sanctuaries, etc., with the result that many important finds disappeared forever in foreign collections and museums without being evaluated and documenting their historical position.

It is one more reason to highlight the Minoan culture, its epoch and its importance for European and world culture by including it in the UNESCO protected monuments.

This will be another trigger to focus on strengthening agencies and structures to promote this very important era of Crete.