By now we always think of food as creation, art, a mix of new ingredients, yet losing the primordial essence of it: surviving.

Man has been able to evolve, travel and discover, having mainly only one motive, nutrition, food.

Of course, the fact that man has not always been interested in gourmet preparations does not mean that they should be of little importance today, at all.

However, there are nuances of prehistoric and ancient nutrition that are still little known to most people today, despite the infinite number of commonalities with our tables today.

Let us start initially by looking at what exactly prehistory is, a detail that often eludes many.

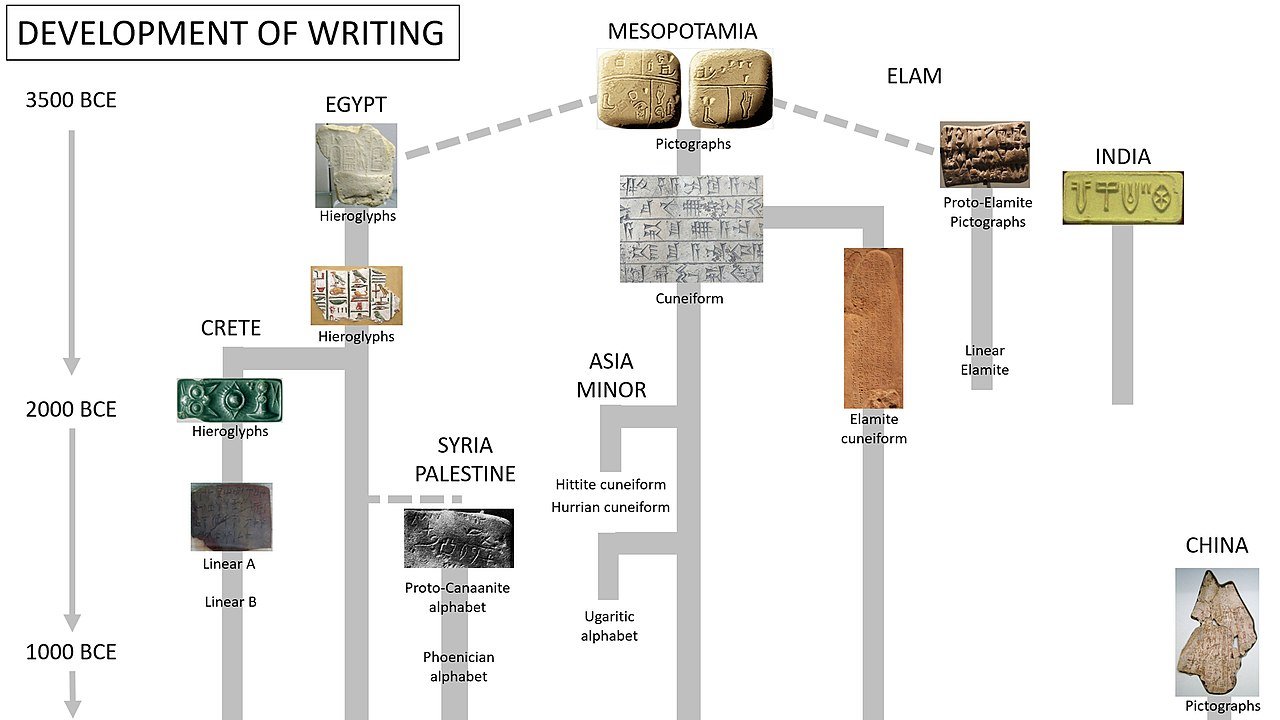

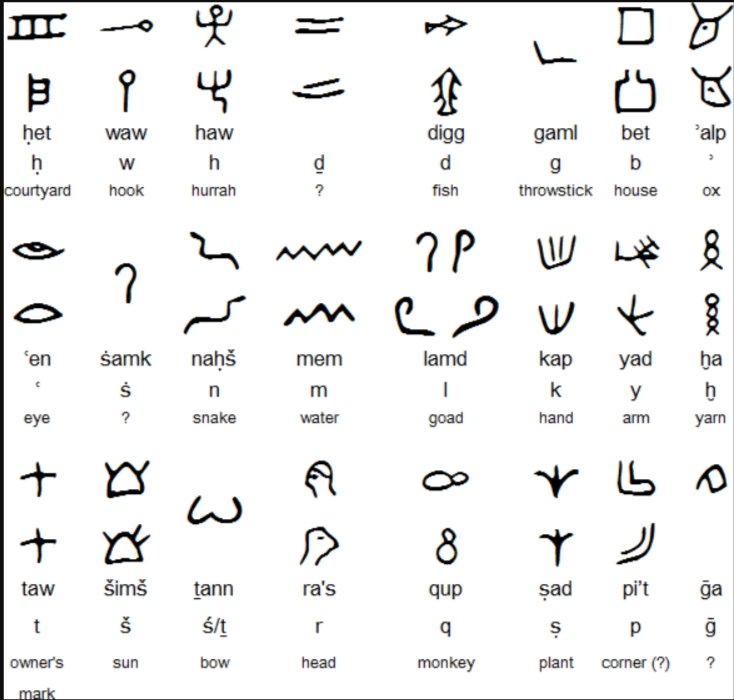

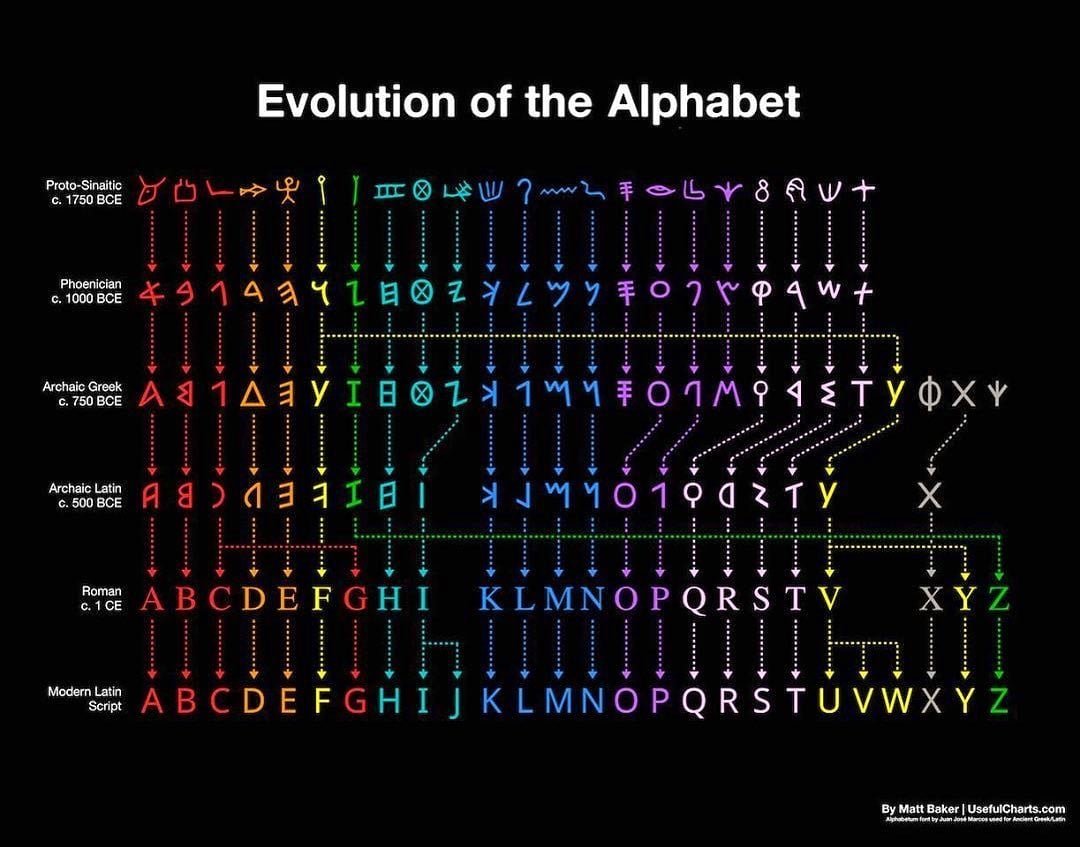

With the Latin term prae-historia, we define all that long period of human existence where the discovery of writing had not yet been made.

The exact subdivision of prehistory is as follows:

● Paleolithic, which lasted nearly 2 million years and ended about 12,000 years ago

● Mesolithic, a period between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago

● Neolithic, the last period of the Stone Age that ended about 4,000 years ago with the invention of writing

The thing that stands out is precisely the long periods of these eras: it may seem obvious but it's not at all, that humans spent more time in prehistory than in history, we were mostly illiterate, which gives a very good idea of how young our race is.

So we will see how starting in the Paleolithic period, man began over the millennia, to develop a more varied and complex diet than his ancestors, albeit at a much slower pace than we might think.

We will certainly not develop the topic solely in the classical scholastic manner, but will also look at dishes from the prehistoric diet that have a direct connection to our tables today.

The Paleolithic, the longest period of prehistory

Speaking of the Paleolithic we mean the longest historical period of prehistory, as well as of human existence.

From the first appearance of homo habilis until the end of the Paleolithic, human nutrition is very limited and characterized by few developments and changes:

Hunting, although considered to be the foundation of his diet, was a very often exhausting and disappointing practice, often dealing with very large prey, thus ending up feeding on carrion and insects, making the human an excellent opportunist rather than a skilled hunter.

In addition, gathering berries and wild fruits was the basis of one's diet, a practice, however, borne by women; in fact, it is thought that it was they who later led to the birth of agriculture: through the seeds that fell on the way back to the villages.

Fishing was also of great importance, but often left on the back burner, dealing with prey that could rarely feed entire groups and families.

The Mesolithic, the first glimmers of true food evolution

With the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago, we see the transition from the Paleolithic to the Mesolithic.

Major climate changes have disruptive effects on the planet's flora and fauna, making it impossible for humans to survive with pre-glaciation habits.

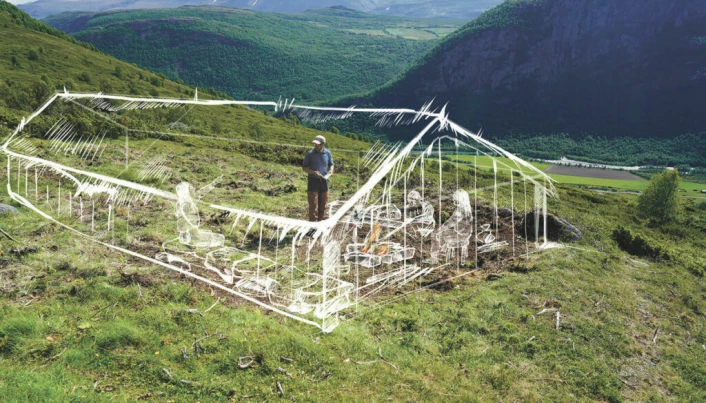

The scarcity of game and large prey prompts humans to embrace a sedentary lifestyle, and to a very different societal organization and their villages.

In fact, the first signs of prey-breeding practices begin, which are no longer killed, but caught and brought back to the villages, creating a kind of prolonged supply over time.

Not unimportant will be the invention of a weapon that will make herd hunting much easier: the bow.

Probably occurring around 6,000 B.C., it helped both in the search for livelihood and in the protection of villages.

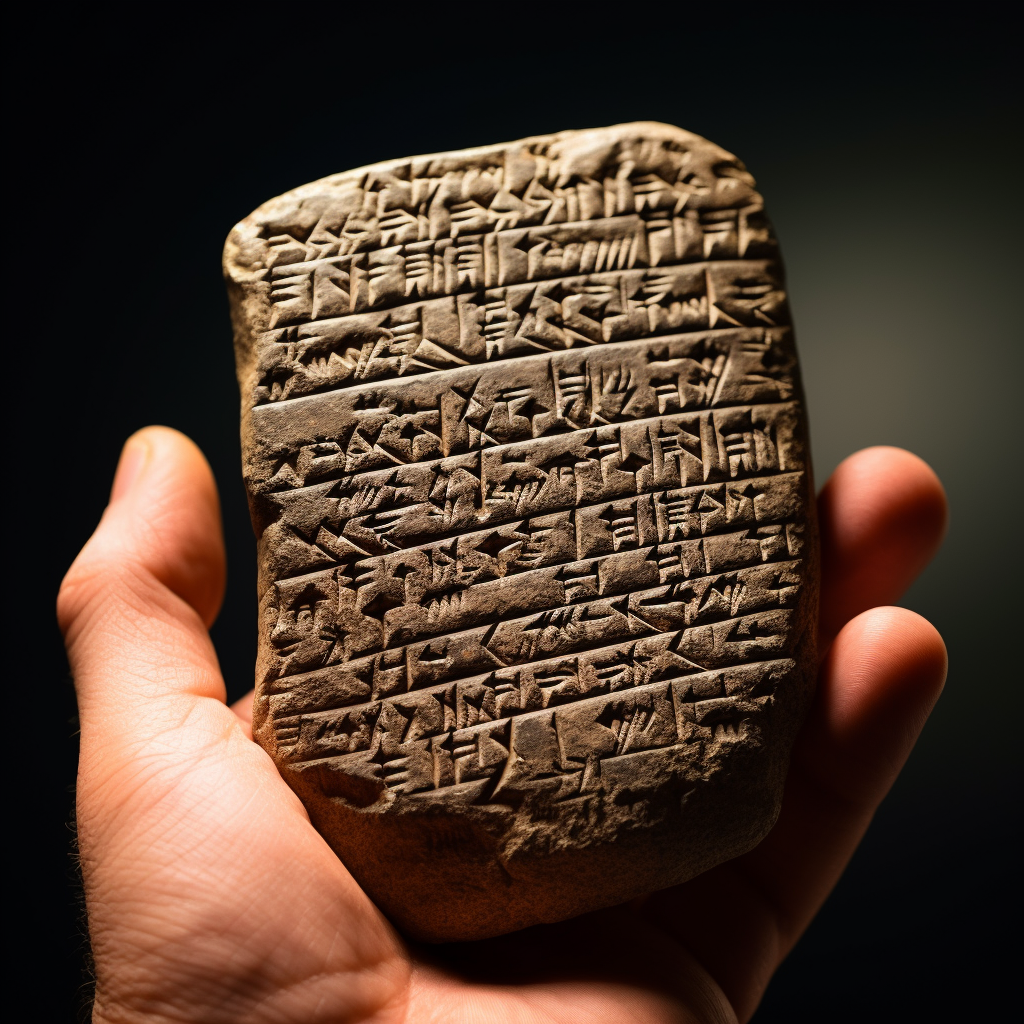

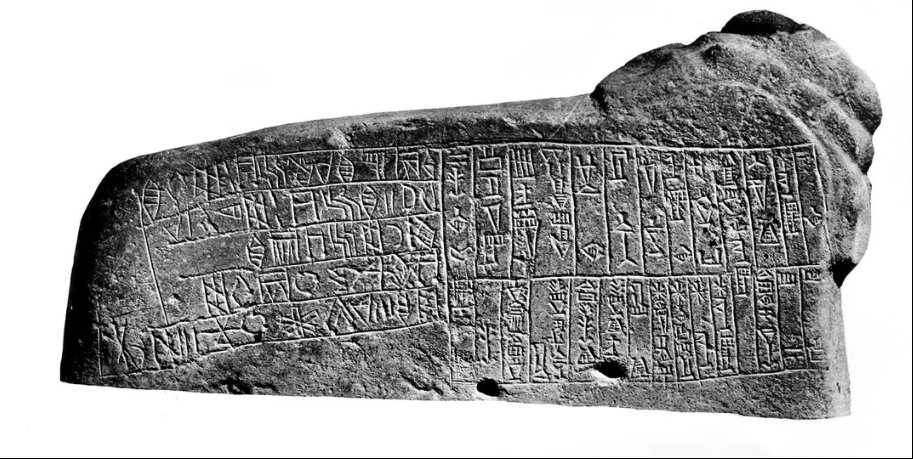

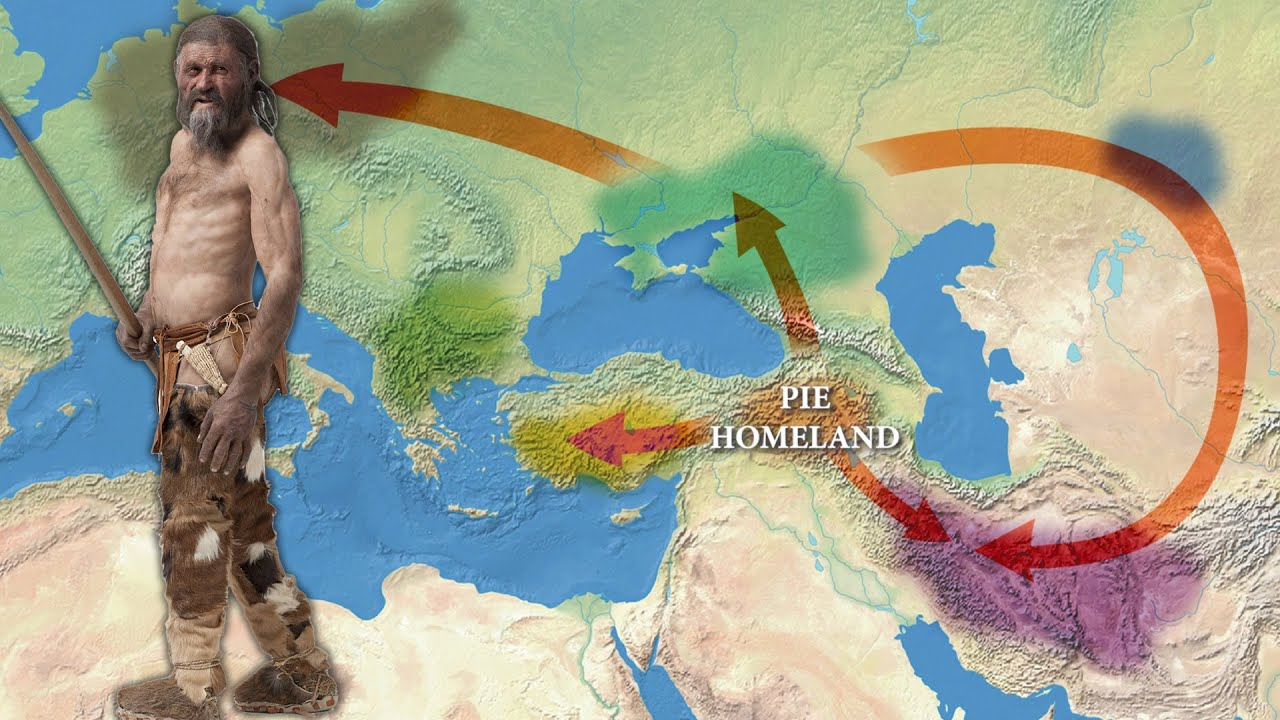

The most significant discovery of the Mesolithic was the cultivation of cereals, in the area of the fertile crescent, Mesopotamia, some assume it was the production of wheat that eliminated the primordial need of the nomadic being.

We certainly cannot assume that the type of the first cereals grown had much in common with those consumed today, since over the centuries man modified the nature of cereals in order to make them more digestible to his organism.

Thanks to his own discoveries, the result of centuries of evolution, human beings went from being hunters and an "opportunistic animal" to a true breeder and farmer.

Neolithic, the pinnacle of development of the prehistoric period

Humans of the period by now have little or nothing in common with their Paleolithic ancestors: they created villages with more complex societal structures and more pronounced hierarchies than before; they also made family organization a priority by dividing even their members' possessions differently.

Inventions such as the wheel and the raft are the greatest technological developments of the period, and among the most significant of our existence.

During these millennia, sheep and cattle raising, and agriculture became the most important and widely used form of livelihood, thus decreasing dangerous practices such as hunting, while drastically increasing one's mortality rate.

In addition, man began to realize that having many children was not just a problem of mouths to feed, but a huge resource at the labor level.

Thus, a population increase never before took place, and thus the birth of large villages and much more populated establishments, the ancestors of cities.

But are there types of foods, whether simple nutritional habits or actual processed foods, that we still have, almost, directly in common with prehistoric humans today?

Yes.

So let us look at 3 examples of handed-down, and obviously modified, foods that have come down to us directly from remote periods in our history.

The consumption of insects, a lost custom

In today's Western culture, the consumption of insects, or derivatives of them, is a taboo.

A practice associated with poor quality food and poor hygienic conditions.

However, we forget to consider that this food was the basis of the prehistoric diet, especially of humans in the Paleolithic period: as mentioned earlier, the opportunistic instinct of humans, led them to eat larvae, grasshoppers and any other available and digestible insect.

It is therefore inferred how entomophagy (feeding on insects), is not a practice characteristic of peoples far from us, but present in the DNA of us all.

Obviously this practice was lost when diet and cuisine evolved?

Wrong, we do in fact have written evidence, including Aristotle's work "historia animalium," where the Greek philosopher spends time explaining to the reader the best methods of tasting various kinds of insects.

One example?

Aristotle declares that female larvae after copulation, are delicious, due to the sublime taste given by the eggs contained in it.

Polenta, an age-old dish, imprinted in our DNA

One may think that the oldest grain-based food is bread: however, we forget that in various Indo-European cultures, since ancient times, another cooked grain-based preparation, in the form of porridge, made its appearance.

Whether it was cooking on heated stones, or boiling in pouches from animal remains, human beings soon began eating doughs made from coarse flours and water.

In the case of cooking on hot stones, the first ancestors of bread were born, more specifically products similar to tortillas and Indian naan.

In the case of boiling, on the other hand, centuries before the appearance of terracotta, humans immersed red-hot stones inside containers of water in order to succeed in bringing products to a boil: in this case they added cereal flour to the water, which they cooked for a not-too-long time, until they obtained the first examples of polenta.

The Sumerians were among the first to prepare this dish, where, with flour made from grains such as millet and rye, they obtained a nutrient-rich mush with a huge energy intake.

It was certainly not the latter who extended it to other territories: the ease of its preparation and the need for only two ingredients meant that polenta played an important role for many peoples in different areas.

Nevertheless, it is important to note how it was the Greeks, in the centuries to come, who in turn made it a true substitute for bread and enriched the flavors through spices and savory sauces.

The name polenta came much later, with the Latin peoples: in fact, polenta comes from the word "puls," literally mush.

Jerky beef, not a modern invention

We all have a clear image of those huge shelves in supermarkets, with packages of jerky of all kinds and with all kinds of flavorings.

Well, what if I told you that this is not a product that is a child of modern drying techniques?

The need to obtain meat at times when hunting was difficult, for climatic reasons mainly, led many peoples of the earth to treat meat in a way that increased its durability.

Various archaeologists have found evidence of dried meat in various tombs in the area of ancient Egypt, dating as far back as 3,500 BCE.

Certainly the primordial methods did not always have the effectiveness of today's drying, in fact often the process to which meat was subjected was salting, despite this we see how a food on our shelves today, has roots far back.

Author:

Giorgio Pintzas Monzani is a Greek-Italian chef, writer and consultant who lives in Milan. His Instagram page can be found here.