by the archaeologist editor group

Echoes in Clay: Deciphering the Cuneiform Enigma

In the great cradle of civilization, the Fertile Crescent, humanity took its first ambitious steps towards recording history. The banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers served as the backdrop for an achievement that would indelibly shape the course of human civilization: the invention of the cuneiform script. Developed by the ancient Sumerians around 3200 BC, cuneiform became the instrument of thought, the ledger of trade, and the record of kings.

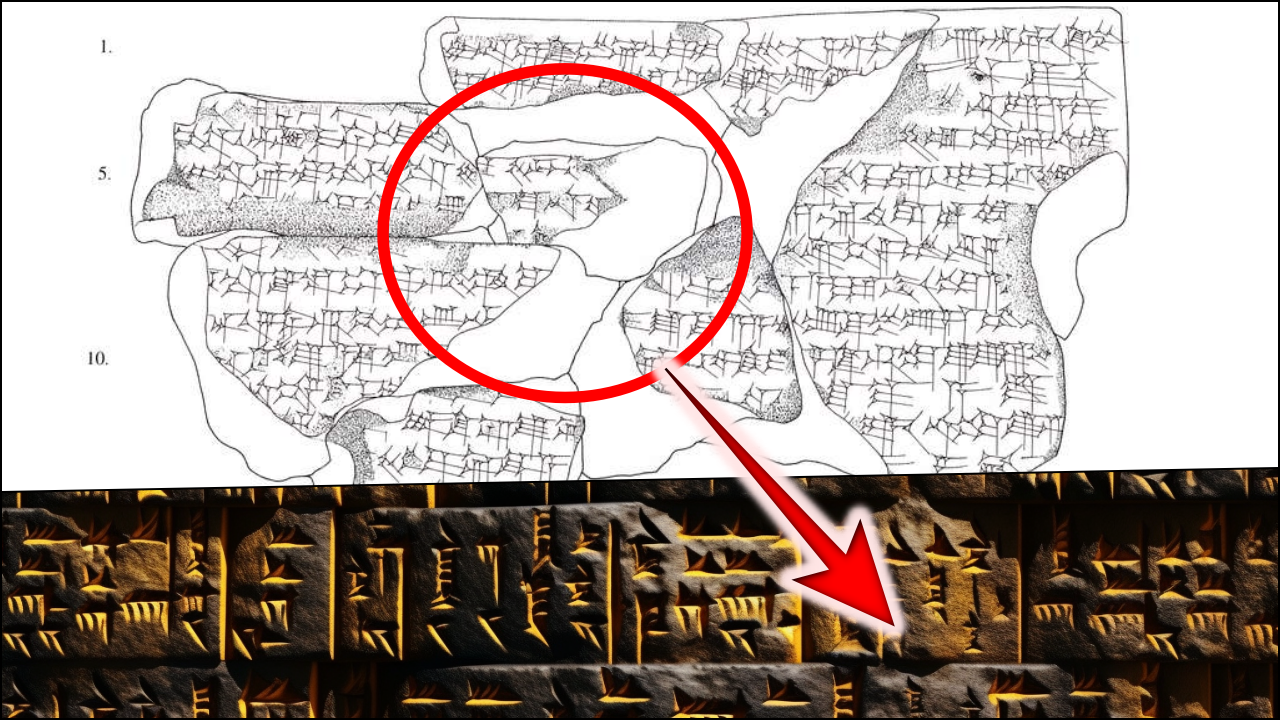

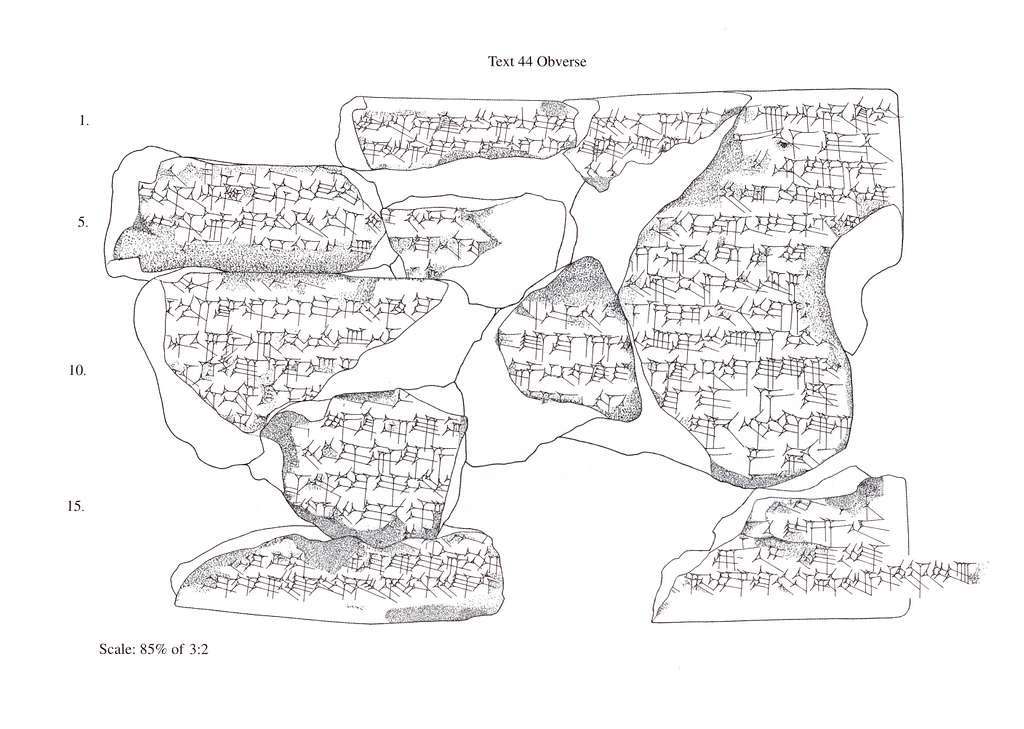

Cuneiform, named for its wedge-shaped marks, was the world's earliest writing system. Its unique characters, pressed into clay tablets with a reed stylus, enabled human expression in a recorded format, immortalizing words, ideas, and events. Over time, it transcended its Sumerian roots, being adapted by the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Hittites, and even Persians, each contributing layers of complexity and diversity to the script. This ancient text, meticulously preserved in the earth's kiln, became our window into the rich tapestry of the ancient Near East.

Yet, despite its crucial role in charting human progress, cuneiform poses a monumental challenge. A vast corpus of texts remains untranslated; the sheer volume of writing, coupled with the complexity and variability of the script, has overwhelmed scholars for centuries. Each character in cuneiform can have multiple phonetic and semantic values, depending on the context. Moreover, the scarcity of bilingual or multilingual texts, like the famous Rosetta Stone that aided the decoding of Egyptian hieroglyphs, has further compounded the problem.

Breaking the Wedge: AI Deciphers Ancient Cuneiform, Unlocking History's Silent Echoes

Only a small number of specialists worldwide can decipher the clay tablets loaded with wedge-shaped symbols because they are so challenging to read. An AI-powered translation engine for ancient Akkadian cuneiform has now been developed by an Israeli team of archaeologists and computer scientists, making it possible to instantly translate tens of thousands of already scanned tablets into English.

The undertaking started off as Gutherz's master's thesis project at Tel Aviv University. The researchers described its neural machine translation from Akkadian to English in a research study that was peer-reviewed and published in the Oxford University Press journal PNAS Nexus in May.

More than 500,000 clay tablets containing cuneiform writing can be found in libraries, museums, and academic institutions around the world. Just a small portion of these tablets have been translated due to the enormous quantity of writings and the small number of Akkadian readers—a language no one has spoken or written in for 2,000 years.

From roughly 3,000 BCE until 100 CE, Akkadian was written and spoken in Mesopotamia and the Middle East. It served as the lingua franca of the time and enabled communication among speakers from various places. Around 2000 BCE, Assyrian Akkadian and Babylonian Akkadian diverged as separate languages. Aramaic gradually replaced Akkadian starting around 600 BCE and eventually spread to a much larger population.

Cuneiform, which involves making wedge-shaped marks on wet clay with a sharpened reed, was used to write Akkadian and its predecessor, Sumerian. The earliest known written languages are Akkadian and Sumerian cuneiform; however, Akkadian texts predominate by a wide margin.

With a new application similar to Google Translate, amateur archaeologists may try their hand at cuneiform interpretation

A complex mathematical formula known as a neural network is used in neural machine translation, which is also used by Google Translate, Baidu Translate, and other translation engines, to produce sentences in foreign languages that are more accurate and naturally constructed than sentences that are translated word-for-word.

Since translation is an art, it might be challenging to quantify what makes a "good" translation, according to Gutherz. The Best Bilingual Evaluation Understudy 4 (BLEU4), an evaluation tool designed in the early 2000s to automatically measure the correctness of machine-generated translations, was utilized by the researchers to rate the translations.

One of the research's major accomplishments was demonstrating that a high-quality translation from Cuneiform to English is feasible. Experts are typically needed to translate the cuneiform first into the Latin transliteration and then substantially into English as part of the present time-consuming research procedure.

In the 2020 publication, the team used AI to convert Akkadian cuneiform to transliterated Latin script with 97% accuracy. This is a much easier method because it translates each cuneiform symbol into a single word while maintaining the original word order.

It is far more difficult to translate Akkadian or transliterated script into English since doing so requires the computer to put complete phrases or sentences together that make sense in English, which is written in a different syntactical order.

Despite the intricacy, according to Gutherz, the AI translations outperformed expectations, even if the software is still in its infancy and far from accurate. Naturally, the AI was more accurate when reading formulaic materials with a set pattern, like royal decrees or divinations. The prevalence of "hallucinations," a term used by artificial intelligence to describe results that the machine creates that are wholly unrelated to the text presented, was higher in literary and poetic writings, such as letters from priests or treaties.

Today, countless stories etched in clay remain locked behind a language barrier, waiting to reveal the secrets of a world that existed more than five millennia ago. The meticulous labor of translation is still underway, gradually illuminating the dusky byways of our past. The task is herculean, but so too is the potential reward: to hear the echoes of ancient voices and weave together the threads of our shared human story. The mystery of cuneiform script remains one of the greatest linguistic enigmas, a testament to the immeasurable intellectual ambition of our ancestors.