Prehistoric Rock Carvings Discovered Beneath Kolsåstoppen in Eastern Norway

A recent discovery beneath Kolsåstoppen, a hill in Bærum, Eastern Norway, has drawn new attention to Norway’s prehistoric rock carvings and the people who created them more than 3,000 years ago.

According to Science Norway, the carvings were found unexpectedly by experienced rock carving hunter Tormod Fjeld while he was driving his daughter to a nearby location. A brief glance at the surrounding terrain led him to notice several exceptionally well-preserved figures etched into the rock.

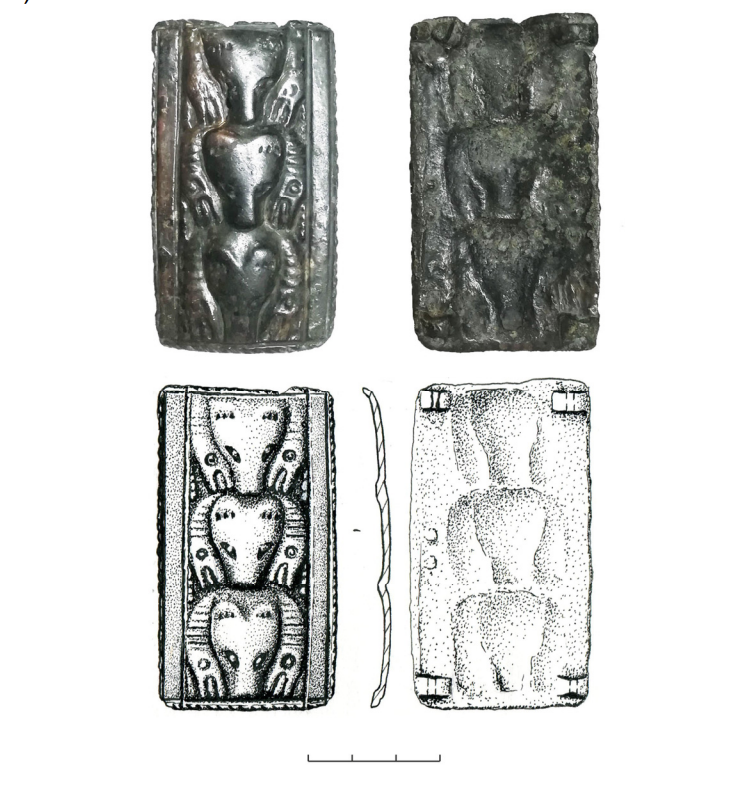

Among the most striking images are large ship carvings, a central and recurring motif in Scandinavian rock art. Some of the ships are carved upright, while others appear inverted. Archaeologists date them to the Nordic Bronze Age (around 1800–500 BCE) and interpret them as symbols of travel, trade, ritual journeys, or cosmological beliefs connected to the sun and the afterlife. Similar ship carvings are known from major rock art sites such as Tanum in Sweden and Alta in northern Norway, pointing to shared symbolic traditions across prehistoric Scandinavia.

In addition to ships, Fjeld identified rarer motifs, including a large footprint showing the sole of a foot and a carved hand with five thick fingers. Human body parts appear far less frequently in Norwegian rock art than animals or ships, making these finds particularly significant. Researchers suggest such images may represent ritual presence, territorial markers, identity, or participation in ceremonial practices, linking people symbolically to sacred landscapes.

Landscape as the Key to Discovery

Fjeld stresses that discovering rock carvings is not a matter of luck alone but requires a deep understanding of the landscape. He explained to Science Norway that factors such as ancient shorelines, sun-facing rock surfaces, and proximity to prehistoric waterways are crucial clues. During the Bronze Age, sea levels were much higher, meaning areas that are now inland were once close to the coast.

This pattern aligns with discoveries across Norway, where many rock carvings are found along former maritime routes. Fjeld notes that reading the landscape in this way not only helps locate carvings but also brings modern observers closer to the people who created them, offering insight into how prehistoric communities understood and interacted with their environment.

A recent discovery beneath Kolsåstoppen, a hill in Bærum, Eastern Norway, has renewed attention on Norway’s prehistoric rock carvings and the people who created them more than 3,000 years ago. According to Science Norway, experienced rock carving hunter Tormod Fjeld made the unexpected find while driving his daughter to a nearby location. What began as a casual glance at the surrounding landscape quickly led to the discovery of several exceptionally well-preserved carvings etched into the rock.

Among the most striking figures are large ship carvings, a recurring and highly significant motif in Scandinavian rock art. Some of the ships are carved upright, while others appear inverted. Archaeologists believe these carvings date to the Nordic Bronze Age (approximately 1800–500 BCE) and interpret them as symbolic representations of travel, trade, ritual journeys, or cosmological beliefs connected to the sun and the afterlife. Similar ship carvings have been documented at major rock art sites such as Tanum in Sweden and Alta in northern Norway, suggesting shared cultural and symbolic traditions across prehistoric Scandinavia.

In addition to the ships, Fjeld identified a large footprint showing the sole of a foot, as well as a carved hand with five thick fingers. Human body parts are relatively rare in Norwegian rock art compared to animals and ships, making these motifs particularly intriguing. Researchers often associate footprints and handprints with ritual presence, territorial markers, or symbolic expressions of identity and ownership. Comparable carvings in other Nordic regions have been interpreted as signs of power, participation in ceremonies, or connections between humans and sacred landscapes.

Understanding the Landscape as a Key to Discovery

Fjeld emphasizes that successful rock carving discovery is not a matter of chance alone but depends on a deep understanding of the landscape. In his interview with Science Norway, he explains that interpreting terrain features—such as ancient shorelines, sun-facing rock surfaces, and proximity to prehistoric waterways—is crucial. During the Bronze Age, sea levels were significantly higher, meaning many carvings that are now inland were once located close to the coast.

This landscape-based approach aligns with patterns seen across Norway, where rock carvings are frequently found along former maritime routes. Beyond helping locate new sites, Fjeld notes that this method brings modern observers closer to the original carvers, offering deeper insight into how prehistoric people interacted with their environment and the meanings behind where and why these images were placed.