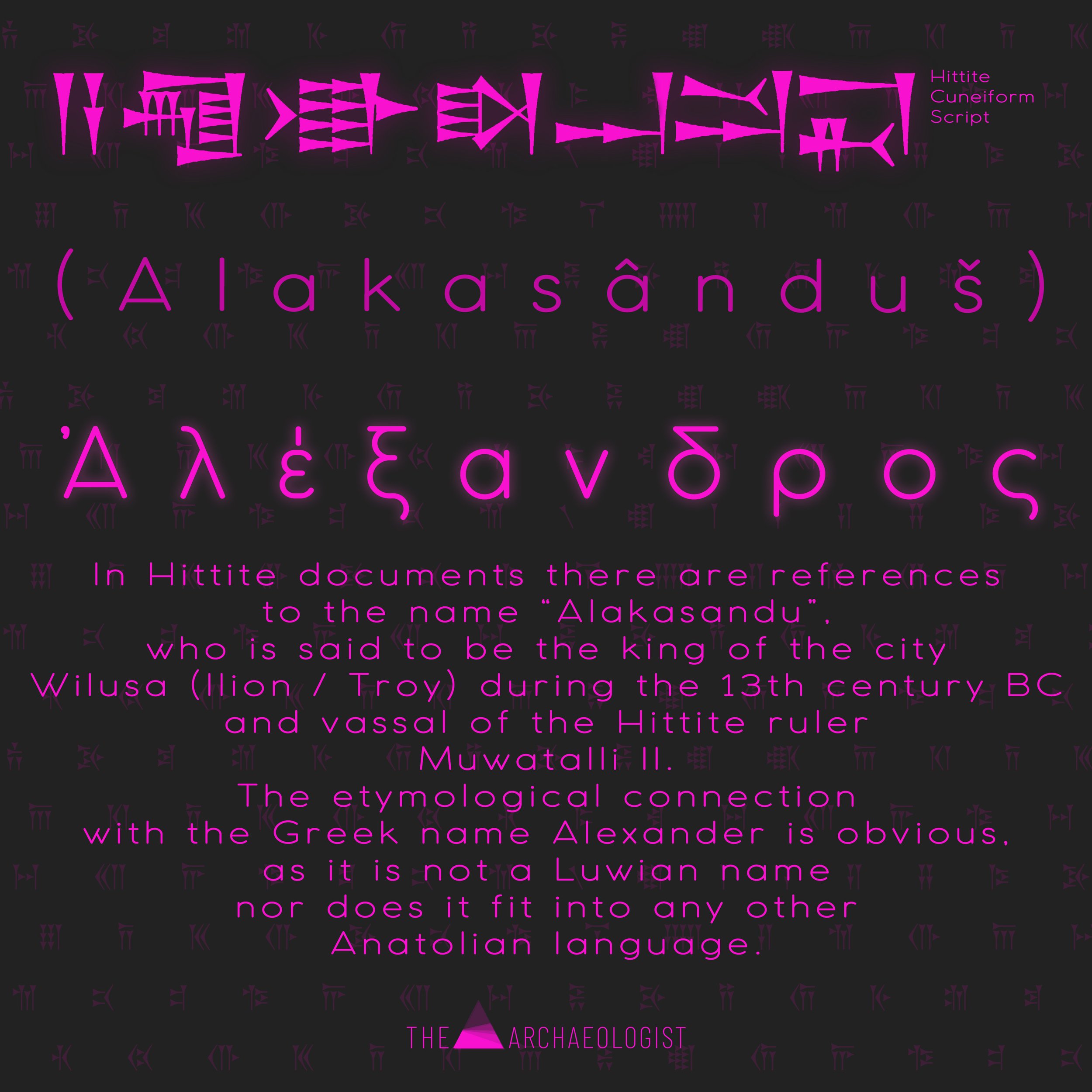

Cross-Cultural Echoes: The Intriguing Case of 'Alakasandu', a Hellenic Echo in Hittite Cuneiform?

In the ancient landscapes of human civilization, two cultures stood tall among the rest: the Hittites of Anatolia and the Mycenaean Greeks of Helladic Mainland. Unbeknownst to many, these cultures had surprising connections in antiquity. One such connection has to do with the fascinating correlation between the Greek name 'Alexander' and a Hittite name: 'Alakasandu'. Scholars have long debated whether these two names, separated by centuries and civilizations, could in fact be one and the same, finding their home in ancient Hittite cuneiform texts.

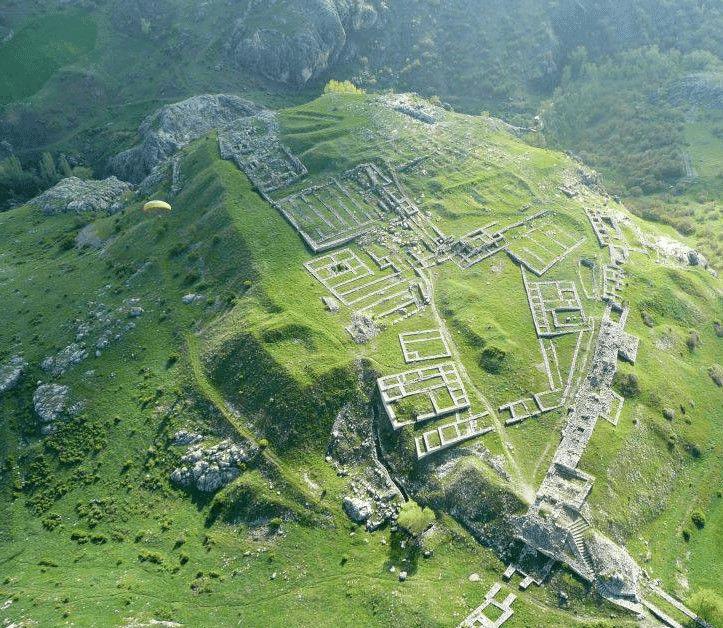

A total of 11,000 tablets with cuneiform texts were discovered after the 19th-century excavations of the Frenchman Charles Texier revealed Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite kingdom, in the hamlet of Boğazköy in modern-day Turkey. The Czech philologist Bedřich Hrozný (1879–1952) conducted the first decipherment of the language on these tablets in 1915 and demonstrated that they were written in the extinct Hittite language.

Aerial view of Hatussa’s citadel.

We may learn a lot about the Middle and Late Bronze Ages in Anatolia (Asia Minor) and the prehistoric Aegean from the archive of the tablets at Hattusa and texts discovered at other Hittite sites. The discovery of Greek names (such as Eteoklis, "Tawagalawa," and Atreas, "Attarissiya") in the Hittite archives by the Swiss archaeologist Emil Forrer in 1924 gave the sense that the shadowy time of the Trojan War may finally come into the light. The Czech philologist Bedich Hrozn (1879–1952) conducted the first decipherment of the language on these tablets in 1915 and demonstrated that they were written in the extinct Hittite language.

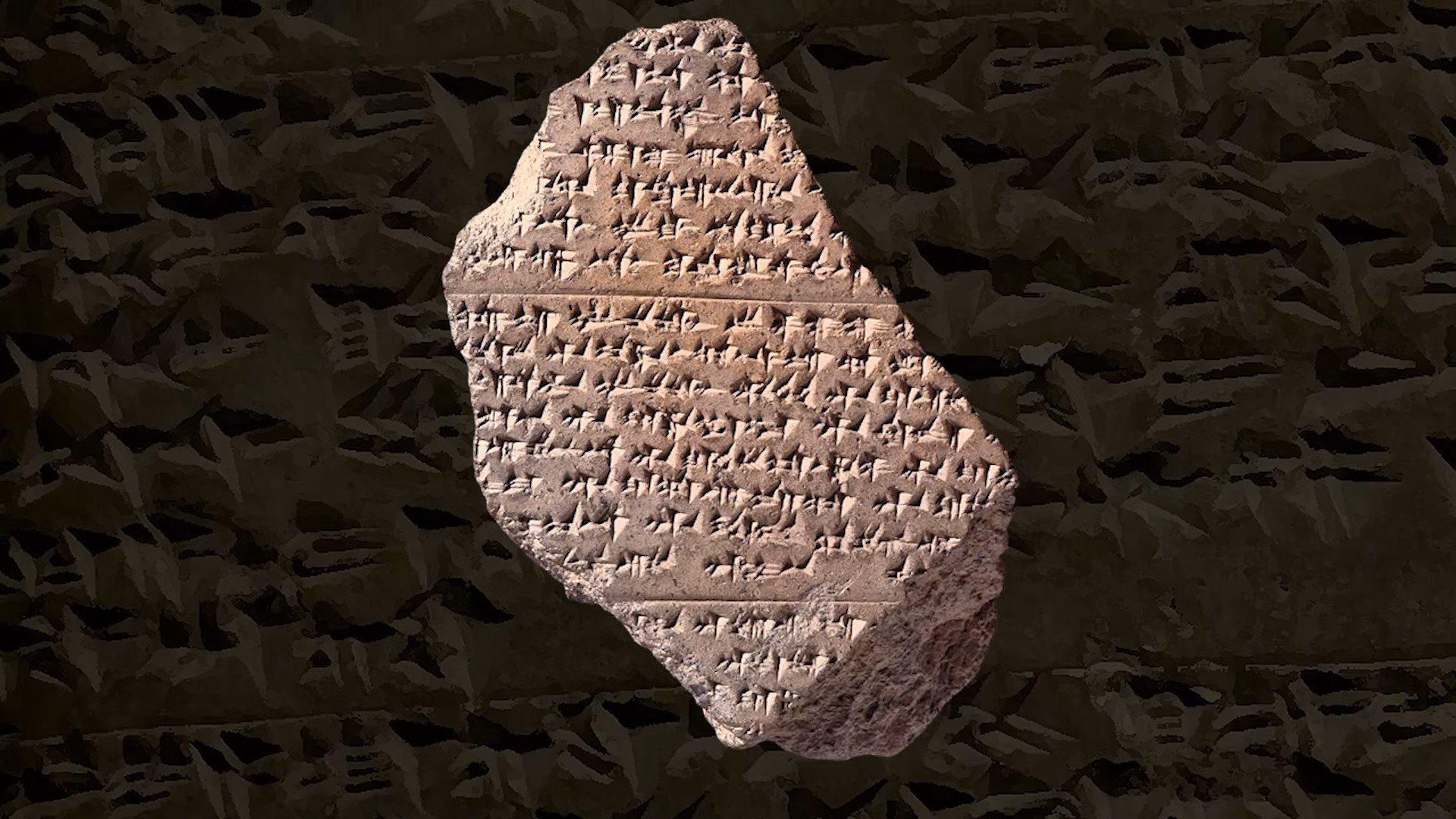

The identification of the names that emphasize the historical context of the Homeric poetry brought the interest to a close. It was also crucial to make mention of a conflict involving the city of "Wilusa" (Ilion/Troy). The monarch of Wilusa, who was a slave to the Hittites (thus referring to the Hittite records), and who had signed a treaty with the Hittite king Muwatali II in the 13th century BC, owes a dowry to the king of "Ahhiyawa" (Achaia), whose name has not been saved. His name was "Alaksandu," and his dowry included some nearby islands (perhaps Tenedos, Imbros, Lemnos, or Lesvos) ("Alaksandu", alternatively called Alakasandu or Alaksandos).

Clay cuneiform tablet; fragment. Hittite treaty between Muwattalli II of Hatti and Alakšandu of Wiluša. Nineteen lines., 1300 BC.

The Hittite Empire and the Name 'Alakasandu'

The Hittite Empire (c. 1600–1178 BCE) thrived in the region that now constitutes modern-day Turkey. The Hittites left behind a rich archive of cuneiform texts, a treasure trove of information for historians and archaeologists. Among these texts, the name 'Alakasandu' appears as the moniker of a significant king. This king was reportedly involved in a treaty with the Hittite ruler Muwatalli II (c. 1295–1272 BCE) in the late Bronze Age.

'Alakasandu' is documented as the king of Wilusa, an ancient city identified with classical Ilios or Ilion, known in the Western tradition as Troy. The debate over whether 'Alakasandu' could be an ancient rendering of 'Alexander' primarily arises from this connection.

The Greek Name 'Alexander'

'Alexander' is a name steeped in Greek tradition, with its roots tracing back to the language's ancient form. It is derived from the Greek 'Alexandros,' literally translating to 'defending men' or 'protector of men,' a compound of 'alexein' (to defend) and 'andros' (of men).

The most famous bearer of this name, Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE), ruled over a millennium after the Hittite king 'Alakasandu.' Alexander's conquests and expeditions spread Greek influence throughout the ancient world, marking a significant period of Hellenistic culture.

The Connection Between 'Alakasandu' and 'Alexander'

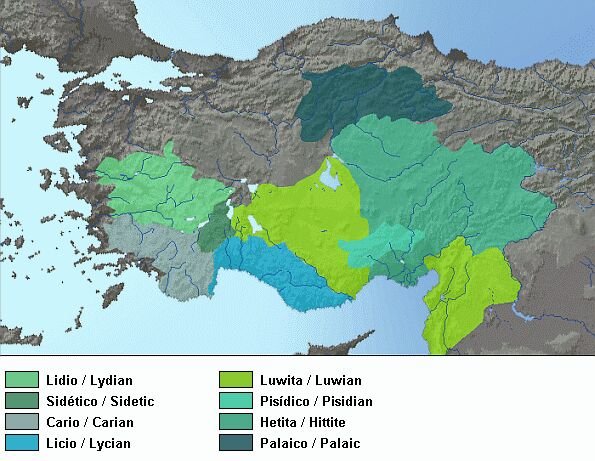

The idea that 'Alakasandu' could be a Hittite rendering of 'Alexander' has its roots in historical linguistics, particularly the study of Luwian, a close relative of Hittite. Scholars suggest that the Luwians, like the Hittites, resided in Anatolia and interacted with the Greeks, facilitating the sharing of names and titles.

Several phonetic and linguistic parallels are drawn between 'Alakasandu' and 'Alexander'. Some researchers suggest that the Hittite and Luwian languages might have phonetically rendered 'Alexander' as 'Alakasandu.' Given the position of Wilusa (Troy) near the Aegean Sea, close to the ancient Greek world, there could have been ample opportunity for cultural and linguistic exchange.

Map of anatolian languages distribution.

Counterarguments and Challenges

Despite these compelling links, there remain significant challenges in definitively asserting that 'Alakasandu' is an ancient form of 'Alexander'.

The complexities of ancient language translation and phonetic rendering often lead to discrepancies and ambiguities. There's always a possibility that similarities between 'Alakasandu' and 'Alexander' are coincidental rather than indicative of a linguistic link.

The question of whether 'Alakasandu' is an early form of 'Alexander' gives us a fascinating glimpse into the interconnections and interactions between ancient cultures. While it might never be conclusively proven, the debate itself illuminates the richness and complexity of our human past. It is a testament to the incredible journey of cultural transmission and the enduring legacy of names across ages and civilizations.

Given that in the Homeric poems everything happened on the occasion of the abduction of Helen by Alexander or Paris, maybe during a "marriage", how close are we to connecting these events with the Trojan War?