A Window into Ancient Mediterranean Languages

In the rich tapestry of Mediterranean history, few artifacts are as enigmatic and potentially illuminating as the Lemnos Stele. Discovered on the Greek island of Lemnos, this ancient stone stele offers a rare glimpse into the Iron Age linguistic and cultural connections between different Mediterranean civilizations. Known also as the Kaminia Stele, named after the area where it was found, this artifact bears inscriptions in a script that challenges both linguists and historians to decode its secrets and the history it carries.

The Discovery of the Lemnos Stele

The Lemnos Stele was uncovered in 1885 near the village of Kaminia on the island of Lemnos, Greece. This find was significant not only because of its age, dating back to the 6th century BC, but also because it features one of the few known inscriptions in the Lemnian language. The stele displays a relief of a male figure, possibly a warrior or noble, alongside inscriptions that are critical for our understanding of ancient languages.

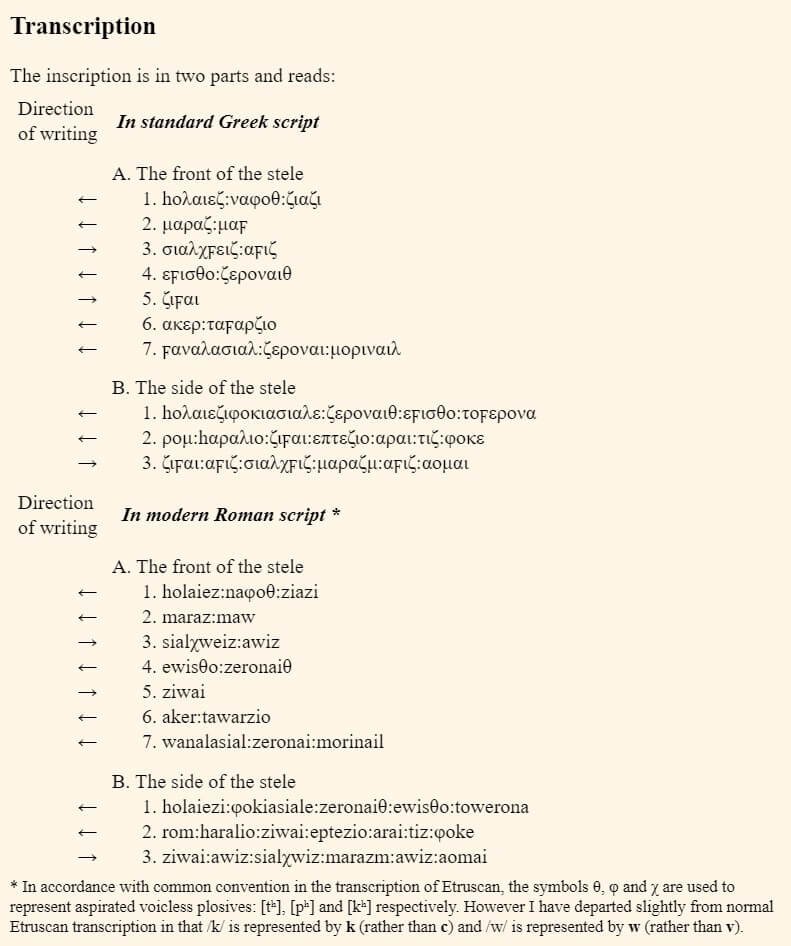

The stele, also referred to as the Stele of Kaminia, was originally part of a church wall in Kaminia before its relocation to the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Dated to the 6th century BC, its historical context is framed by the Athenian invasion led by Miltiades in 510 BC, which initiated the “hellenization” of Lemnos. The stele features a low-relief bust of a man and bears an inscription in an alphabet akin to the western ("Chalcidian") Greek alphabet. The inscription, arranged in the Boustrophedon style, has been transliterated and has started to be meaningfully translated following advancements in the understanding of Etruscan, facilitated by linguistic comparisons.

Linguistic Significance and similarities to the etruscan language

The inscriptions on the Lemnos Stele are primarily in the Lemnian language, which shows intriguing similarities to the Etruscan language, spoken contemporaneously in regions of what is now modern Italy.

The inscription comprises 198 characters, which are organized into 33 to 40 words; in some cases, word separation is marked by one to three dots. The text is divided into three sections on the front, with two sections written vertically (1; 6-7) and one horizontally (2-5). A decipherable segment, "sivai avis šialχvis" ('lived forty years', B.3), mirrors the Etruscan phrase "maχs śealχis-c" ('and forty-five years'), suggesting it commemorates the lifespan of an individual, possibly named Holaie Phokiaš, referred to as "holaiesi φokiašiale" ('to Holaie Phokiaš', B.1). This individual might have once held the title "maras," as indicated by "marasm avis aomai" ('and was a maras for one year', B3). Intriguingly, the text includes the term "naφoθ," akin to the Etruscan "nefts" ('nephew/uncle'), indicating a possible linguistic borrowing from Latin nepot-, which implies migration from or cultural contact with the Italic peninsula. Notably, in 1893, G. Kleinschmidt suggested the translation "haralio eptesio" could refer to Hippias, a tyrant of Athens who is believed to have died on Lemnos in 490 BC, indicating political connections reflected in the inscription.

This similarity has led scholars to hypothesize about ancient migrations and cultural exchanges across the Mediterranean. The Lemnian language, as evidenced by the stele, might represent a linguistic bridge between cultures of the Aegean and the Italian Peninsula, offering clues to the prehistoric movements and interactions of these ancient peoples.

The lemnian language

The Lemnian language, spoken on the Greek island of Lemnos during the latter part of the 6th century BC, serves as a crucial link in understanding the linguistic landscape of the ancient Mediterranean. Additional inscriptions found on pottery fragments and a newer inscription from Hephaistia underscore that Lemnian was a living language within the community. This linguistic connection is further solidified by the stele's use of the Western Greek alphabet, which shares similarities with the archaic variant used for Etruscan in southern Etruria, suggesting a shared or parallel linguistic evolution.

The alignment of Lemnian with Etruscan and Raetic, established through linguistic features such as unique dative cases and specific lexical correspondences, underscores a profound cross-regional linguistic and cultural exchange. Notable examples include the use of similar genitive and past tense constructions and numbers with comparable morphological structures. Despite these linguistic ties, the theory of a shared Tyrsenian language family, which includes Lemnian, posits a broader, perhaps pre-Indo-European, linguistic substrate in Europe.

Inscribed altar base of Hephaistia. Photograph courtesy of SAIA and Carlo de Simone.

This perspective is supported by recent genetic studies indicating that Etruscans were autochthonous to Italy, with no significant genetic links to Anatolia, suggesting that the language similarities found in Lemnos might reflect ancient migrations from the Italian peninsula rather than a direct connection with the Sea Peoples or other groups. This linguistic and genetic isolation frames the Lemnian language not only as a relic of ancient linguistic diversity but also as a window into the interactions that shaped the ancient Mediterranean world.

greek tradition on the Pelasgians and their Language

According to Greek tradition, the Pelasgians occupied large swaths of Greece before the arrival of the Greeks, notably in regions like Thessaly and Attica. Homer references them in the Iliad as allies of Troy, and in the Odyssey, they are depicted among the tribes populating the ninety cities of Crete.

Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, talked about the Pelasgians, an ancient people who lived in various parts of Greece before the Greeks. He mentioned that these people, including those from the island of Lemnos, once lived in the region of Attica but were later expelled by the Athenians. Regarding their language, Herodotus wasn't sure exactly what language the Pelasgians spoke. However, he suggested that if we look at the language of the Pelasgians who were still around in his time—like those living in Creston and those who founded cities near the Hellespont after leaving Athens—we might conclude that the Pelasgians spoke a language that was very different from their Greek neighbors. He noted that in places like Creston and Placia, the people spoke a unique language that was different from any nearby languages, indicating that they preserved their original Pelasgian language even after moving to new areas.

Archaeological and Historical Context

The physical features of the stele suggest that it may have served as a grave marker or a monument celebrating the achievements of the individual depicted. The style of the carving and the script form a crucial part of the archaeological record, helping to place Lemnos within the broader networks of trade and cultural exchange in the Iron Age Mediterranean.

From an archaeological standpoint, the Lemnos Stele helps to fill a gap in our understanding of the socio-political structures of the island during the 6th century BC. The presence of such an inscription suggests a society with its own distinct identity and language yet clearly participating in the cultural and material exchanges that characterized the Mediterranean region at the time.

Challenges in Decipherment

The decipherment of the Lemnian language remains incomplete, with many challenges still to overcome. Unlike the Rosetta Stone, which provided a bilingual key to unlocking the Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Lemnos Stele offers text only in Lemnian, limiting direct comparison with better-understood languages. Each word and symbol on the stele is a puzzle piece in the broader picture of Iron Age languages, requiring meticulous analysis to understand its syntax and vocabulary.

The Lemnos Stele stands as a testament to the complex web of ancient Mediterranean civilizations. As both an artifact of cultural expression and a bearer of cryptic linguistic data, it challenges and enlightens modern scholars. In studying the Lemnos Stele, we delve deeper into the past, piecing together the movements, exchanges, and interactions that shaped the ancient world. The ongoing study of this remarkable stele not only enriches our understanding of ancient languages but also enhances our appreciation of the cultural and historical connections that link diverse societies across time and space. The decipherment and interpretation of the Lemnian inscriptions continue to hold the promise of unlocking further secrets of the ancient Mediterranean, making the Lemnos Stele a focal point of historical and linguistic research in the years to come.