The Labrys as a Cultural Keystone from Çatal Höyük to Knossos

The odyssey of the labrys, a symbol par excellence of divine authority and ritual, commences long before its renowned association with the Minoan civilization. Originating within the prehistoric tapestry of Anatolia, specifically at the site of Çatalhöyük, the labrys' presence can be traced back to a society flourishing from 7500 to 5700 BCE. Already from that time, the double axe emerges not merely as a tool but as a ceremonial artifact, integral to the worship practices of early agrarian communities.

As the embodiment of power and religious life, the labrys traversed maritime routes from the Anatolian and Greek mainlands to Minoan Crete, where it became a central motif in the island's intricate palatial complexes and religious iconography, reflecting a narrative of cultural transmission and adaptation that spanned across centuries.

From Neolithic Anatolia to Minoan Crete: The Journey of the Labrys

The ancient Greeks referred to the double axe as "labrys," a term steeped in mystery and hailing from the depths of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods of Anatolia. This word had already found relevance during the Minoan era, hinting at a connection with the term "labyrinth." Plutarch notes that 'labrys' is the Lydian term for 'axe,' stating: "The Lydians call the double-edged axe 'labrys.'"

Originating in the East, the double axe's earliest representations are traced back to Çatalhöyük, an early Neolithic proto-city in Anatolia. Its depiction was not only artistic but symbolic, reflecting the complex, maze-like layout of the settlement. The oldest artifact of a double axe unearthed to date was at Gürcü Tepe, situated east of Çatalhöyük, within a similar cultural sphere. Gürcü Tepe's rural character suggests that the double axe served an apotropaic role, warding off evil.

At Çatalhöyük, one encounters the double axe intermingled with bull iconography within the community's intricate art. Bulls are rendered with detailed anatomical precision, symbolizing virility and fecundity within this early agrarian society. The double axe, appearing both in art and as tangible relics, likely bore a sacred import, potentially linked to male divinities or sacrificial rituals. These symbols reflect the spiritual practices and complex social structures of one of humanity's initial urban centers.

The emblematic significance of the double axe on Crete is believed to stem from the Neolithic settlers' religious beliefs, which were characterized by reverence for an Earth Mother Goddess, indicative of the island's enduring spiritual traditions. In Minoan Crete, the labrys fulfilled both ritual and votive roles. It was the primary instrument in the ceremonial sacrifice of sacred bulls and was also offered in burial rites, caves, and peak sanctuaries. Seals and the Archanes Script provide evidence of the double axe's significance, which was so ingrained in Minoan culture that it predates the Prepalatial Period. The Minoan religion was anchored in the veneration of the Mother Goddess, a primordial figure of fertility, reproduction, and the cyclical rebirth of nature.

The double axe holds a venerable place in the mythology of ancient Near Eastern cultures, symbolizing the might of deities like the Hurrian sky and storm god, Teshub. In Hittite and Luwian traditions, this god was known as Tarhun, often depicted wielding a double axe alongside a triple thunderbolt—a clear emblem of his dominion over storms. This formidable storm god is also depicted on a relief brandishing a double axe, a symbol of his power, as he stands over a bull. In parallel, the Greek god Zeus is traditionally depicted hurling thunderbolts, employing the labrys, or pelekys, as his instrument to command the storm. Intriguingly, the modern Greek term for lightning, "astropeleki" (ἀστροπελέκι), translates to "star-axe," perpetuating the ancient association of the axe with celestial power.

The worship of the double axe on the Greek island of Tenedos and other locations in southwestern Asia Minor is evidence that this reverence persisted into classical antiquity. The labrys also found its place in the worship practices associated with the Anatolian thunder god, further evidenced in the Hellenistic period with the cult of Zeus Labrayndeus, where the labrys continued to be a potent symbol of divine storm-making power. This continuity of the double axe's symbolism across different cultures and eras reflects its enduring significance in the religious and mythological landscape of the Mediterranean and Near East.

The depiction of bulls and double axes across various ancient cultures—from the bull frescoes of Çatalhöyük and Minoan bull-leaping iconography to the imagery of the Hittite and Luwian god Tarhun wielding a double axe over a bull—suggests a hypothetical cultural linkage. These symbols, recurring throughout ancient Anatolia and Crete, may signify a shared mythological language where the bull symbolizes strength and fertility, and the double axe represents divine authority, reflecting an enduring tradition of reverence and ritual that transcends regional and temporal boundaries.

A Roman bronze ensign of Jupiter Dolichenus. One can make out other deities including Hercules, Victoria, Luna and perhaps in the lower right hand corner is Mars. This amazing piece is on display in the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, Hungary.

The Linguistic Enigma: Labrys, labraunda and the Greek Labyrinthos

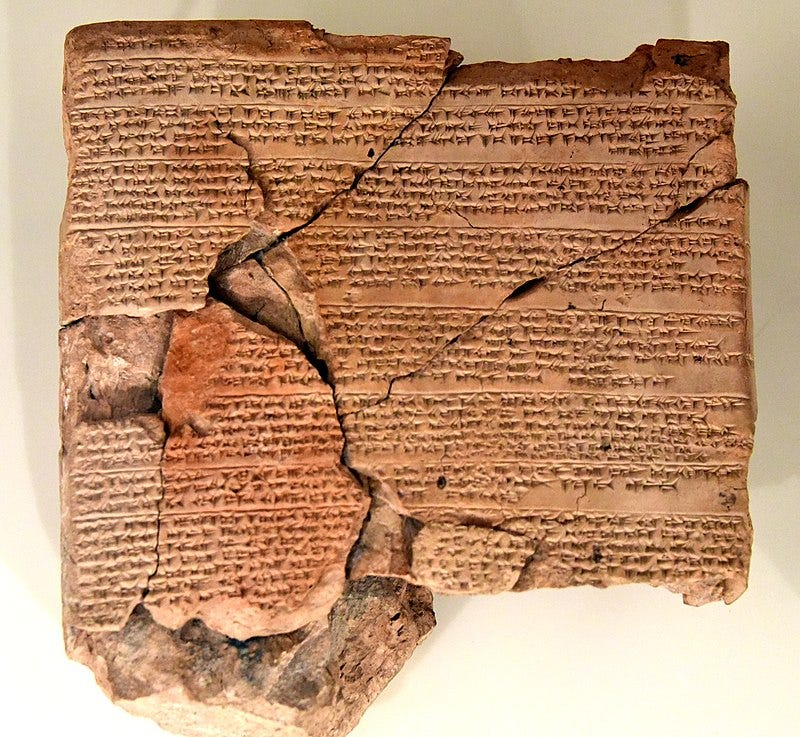

The path of the labrys intertwines with the evolution of language, presenting a fascinating enigma that captivates linguists and historians alike. The term 'labrys' finds its echoes in the pre-Greek word 'labyrinthos,' an association derived from the interpretation of ancient texts, most notably a Linear B tablet that references the 'Mistress of the Labyrinth.' This coupling of the labrys with the intricate and complex structure of the labyrinth carries profound implications, suggesting a sacred dimension wherein the axe is not only a symbol of divine power but also an architectural metaphor. The linguistic fluidity of ancient Greek, where phonemes like 'd' and 'l' could interchange (Dabraundos, dabrys), adds layers of complexity to this enigma, inviting scholars to delve deeper into the maze of historical language development.

The word "labrys," which the Lydians or Carians used to refer to a double-edged axe, also serves as the basis for the name of the renowned labyrinth of Knossos, indicating an intriguing cultural connection between the civilizations of Western Anatolia and Minoan Crete. The labyrinth is often interpreted as the "place of the axe," a phrase that resonates with the central role of the labrys within both Minoan and Carian sacred spaces. The significance of the labrys is further highlighted by its enduring presence in Carian religious sites, such as Labraunda, where it was revered as a holy artifact.

The term "labrys," first noted in English in 1901 according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is intimately linked to the ancient Carian sanctuary of Labranda. This connection highlights the significance of the labrys as a sacred object. The sanctuary's name, Labranda, is directly derived from this term, suggesting that it was a place where the labrys held religious importance. This interpretation casts the sanctuary not just as a geographical location but as a spiritual center dedicated to the veneration of the labrys, reinforcing its status as a potent symbol of divine or royal power in ancient Anatolia.

It is amazing how symbols and gods from different cultures came together at Labraunda. In the mountainous terrains of Caria, five kilometers west of Ortaköy, Mugla Province of modern Turkey, the labrys finds a sacred echo at this site, which is steeped in divine resonance. Here, the double-headed axe stands beside Zeus Labrandeus, a syncretic deity embodying the storm's might, a testament to the symbol's enduring sacral status. Revered along with the Olympian gods, it shows that religious and artistic traditions from Anatolia and Greece were constantly exchanging ideas and images. The presence of the labrys in this sacred milieu underscores its dynamic role as a venerated object of worship, a focal point of divine communion, and an emblem of spiritual continuity in the ancient Mediterranean tapestry.

A legendary account tells of a golden double-headed axe that held a place of honor in the Lydian capital of Sardes. King Gyges of Lydia gave the Carians this sacred labrys as a thank-you gift for their military assistance. The complexity of such an exchange underlines the ceremonial importance of the labrys, a symbol not easily relinquished or transferred between peoples. Once in the possession of the Carians, it was enshrined in the Temple of Zeus at Labranda, emphasizing its continued ritual significance.

In the city of Halicarnassus, the labrys became a numismatic emblem, frequently depicted on coinage, signaling its broader symbolic currency in Carian society. The museum in Bodrum houses coins that not only depict the familiar head of Apollo but also the esteemed figure of Zeus Labraundeus, distinguishable by the double-bladed Carian axe. This consistent iconography across various mediums and contexts, from coins to sanctuaries, denotes the profound link between the labrys and the divine, thereby weaving a thread of shared cultural and religious (and now also genetic) identity between the civilizations of the Greek mainland, Minoan Crete, and Western Anatolia.

Scholarly Discourse and Alternative Interpretations

Amidst the converging lines of historical evidence and myth, the origin and meaning of 'labyrinthos' spark ongoing scholarly debate. While the association with the labrys suggests a lineage tied to Minoan ritual spaces, other scholars cast a wider net, proposing alternatives such as a linguistic link to Greek 'laura' or even a borrowing from Carian terms. These discourses reflect the complexities and challenges inherent in unraveling the etymological threads of ancient words, with each interpretation offering a unique perspective on the intersections of language, archaeological evidence, culture, and religion. As the labrys continues to serve as a nexus for these discussions, its journey from a utilitarian axe to a profound cultural symbol encapsulates the rich spectrum of ancient Mediterranean spirituality and the scholarly pursuit to understand it.