A script is any particular system of writing or the written means of human communication. It is also a kind of early human technology, a basic form of communication that began simply as lists of goods and evolved into a more sophisticated means of conveying thoughts and feelings, and this, in time, became the script in which the literature of the culture was set down.

The Phoenician alphabet

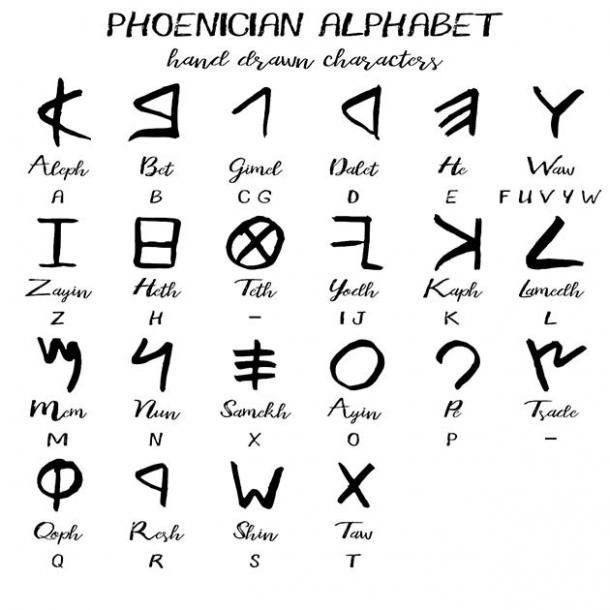

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet (more specifically, an abjad) known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region.

The Phoenician alphabet is also called the Early Linear script (in a Semitic context, not connected to Minoan writing systems) because it is an early development of the pictographic Proto- or Old Canaanite script into a linear, alphabetic script, also marking the transfer from a multi-directional writing system, where a variety of writing directions occurred, to a regulated horizontal, right-to-left script. Its immediate predecessor, the Proto-Canaanite, Old Canaanite or early West Semitic alphabet, used in the final stages of the Late Bronze Age, first in Canaan and then in the Syro-Hittite kingdoms, is the oldest fully matured alphabet, thought to be derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

"Phoenician proper" consists of 22 consonant letters only, leaving vowel sounds implicit—in other words, it is an abjad—although certain late varieties use matres lectionis for some vowels. As the letters were originally incised with a stylus, they are mostly angular and straight, although cursive versions steadily gained popularity, culminating in the Neo-Punic alphabet of Roman-era North Africa. Phoenician was usually written right to left, though some texts alternate directions (boustrophedon).

Beginning in the 9th century BC, adaptations of the Phoenician alphabet thrived, including Greek, Old Italic, and Anatolian scripts. The alphabet's attractive innovation was its phonetic nature, in which one sound was represented by one symbol, which meant only a few dozen symbols to learn. The other scripts of the time, cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, employed many complex characters and required long professional training to achieve proficiency, which restricted literacy to a small elite.

Another reason for its success was the maritime trading culture of Phoenician merchants, which spread the alphabet into parts of North Africa and Southern Europe. Phoenician inscriptions have been found in archaeological sites at a number of former Phoenician cities and colonies around the Mediterranean, such as Byblos (in present-day Lebanon) and Carthage in North Africa. Later finds indicate earlier use in Egypt.

The alphabet had long-term effects on the social structures of the civilizations that came into contact with it. Its simplicity not only allowed its easy adaptation to multiple languages, but it also allowed the common people to learn how to write. This upset the long-standing status of literacy as an exclusive achievement of royal and religious elites—scribes who used their monopoly on information to control the common population.

The Euboean alphabet

The Euboean alphabet was a western variant of the early Greek alphabet, used between the 8th and 5th centuries BC. It was used in the island of Euboea (notably the cities of Eretria and Chalkis) and in related colonies in southern Italy, notably in Cumae and in Pithikoussai. It was through this variant that the Greek alphabet was transmitted to Italy, giving rise to the Old Italic alphabets, including Etruscan, and ultimately the Latin alphabet. Some of the distinctive features of Latin as compared to the standard Greek script are already present in the Euboean model. In Greece, this and other local variants were replaced by the standard Greek alphabet, which is based on eastern Ionic Greek variants from the 4th century BC.

Euboean alphabet tended to use certain variant forms of the standard letters, several of which also foreshadowed the forms adopted by the Italic scripts. Γ was written like a (rounded or pointed) Latin C. Δ was written with the left edge vertical and the other two sides oblique, like a pointed Latin D. Λ was often written more like a Latin L, with a rightward hook at the bottom. Π was often written with a rounded top, approaching the shape of Latin P (but without the curve touching the vertical stem in the middle). Ρ, in turn, often had a downward tail, resembling Latin R.

The Marsiliana abecedarium (ca. 700 BC) shows an archaic variant of the Etruscan alphabet practically identical to the Western Greek alphabet, except for the presence of a Ξ or Samek.

Apart from the omission of samek (Ξ) and the addition of ΥΧΦΨ, the alphabet is identical to the Phoenician alphabet.

The Etruscan alphabet

The Etruscan alphabet was the alphabet used by the Etruscans, an ancient civilization of central and northern Italy, to write their language from about 700 BC to sometime around 100 AD.

The Etruscan alphabet derives from the Euboean alphabet used in the Greek colonies in southern Italy, which belonged to the "western" ("red") type, the so-called Western Greek alphabet. Several Old Italic scripts, including the Latin alphabet, derived from it (or simultaneously with it).

The Etruscan alphabet originated as an adaptation of the Euboean alphabet used by the Euboean Greeks in their first colonies in Italy, the island of Pithekoussai, and the city of Cumae in Campania. In the alphabets of the West, X had the sound value [ks], and Ψ stood for [kʰ]; in Etruscan, X = [s], Ψ = [kʰ] or [kχ] (Rix 202–209).

The earliest known Etruscan abecedarium is inscribed on the frame of a wax tablet in ivory, measuring 8.8×5 cm, found at Marsiliana (near Grosseto, Tuscany). It dates from about 700 BC and lists 26 letters corresponding to contemporary forms of the Greek alphabet, including digamma, san, and qoppa, but not omega, which had still not been added at the time.

The shapes of the Archaic Etruscan and Neo-Etruscan letters had a few variants, used in different places and/or in different epochs. Notably, opposite letters were used for /s/ and /ʃ/, depending on the locality. Shown above are the glyphs from the Unicode Old Italic block, whose appearance will depend on the font used by the browser. These are oriented as they would be in lines written from left to right. Also shown are SVG images of variants shown as they would be written right to left, as in most of the actual inscriptions.