Long shrouded in mystery, the Great Sphinx of Giza is a colossal limestone statue, resembling the body of a lion with a human head. A mainstream consensus in Egyptology holds that the Sphinx was carved during the 4th Dynasty (Old Kingdom) reign of Pharaoh Khafre (c. 2558–2532 BC), who built the second-largest of the Giza pyramids. Most modern scholars identify the Sphinx’s face as Khafre’s and view the monument as an integral part of his pyramid complex. This report looks at the proof that connects the Sphinx to Khafre and shares the views of top Egyptologists based on different types of evidence: historical texts, archaeological context, style analysis, inscriptions, and geological data. It also notes any significant academic debate (such as minority views attributing the Sphinx to Khafre’s relatives) and briefly contrasts alternative or fringe theories for context. Throughout, the focus is on the consensus of mainstream Egyptology rather than speculative claims.

Historical Records and Ancient Texts

No textual record from Khafre’s own time explicitly mentions the Sphinx or its construction – a point often noted by scholars. The original name or purpose of the statue was not recorded in surviving Old Kingdom inscriptions; in fact, the Sphinx complex appears to have been left unfinished at the end of Khafre’s reign, so a formal cult or dedication may never have been established. As a result, later historical sources become key.

New Kingdom texts: By the New Kingdom (c. 1400 BC), the Great Sphinx had come to be revered as a manifestation of a solar deity. The most famous text is the Dream Stele of Thutmose IV, erected between the Sphinx’s paws around 1401 BC. The Dream Stele describes how Prince Thutmose (not yet king) fell asleep in the shadow of the sand-obscured Sphinx and had a dream in which the god – identified with Horemakhet (Horus-in-the-Horizon) and Khepri (the morning sun) – promised him kingship if the sand were cleared. Crucially, the inscription on this stele links the Sphinx to Khafre. The text is damaged, but when first translated it was noted that a royal cartouche appears in line 13, likely that of Khafre. This “mention of…Pharaoh Khafre…has long been taken as confirmation that the same pharaoh built the Sphinx”. In other words, Egyptians of Thutmose IV’s time seemingly believed the Sphinx was associated with Khafre, perhaps preserving a memory of its builder. (Some have debated this reading – fringe writers suggest the hieroglyphs might not name Khafre – but the mainstream view accepts the original interpretation that Khafre is named on the Stele.) Aside from the Dream Stele, other New Kingdom inscriptions refer to the Sphinx by epithets (Horemakhet, etc.) and record restorations. For example, Thutmose IV’s Stele itself was actually carved on a reused door lintel from Khafre’s nearby temple, suggesting a conscious effort to connect the monument to Khafre’s legacy.

Later Egyptian records: Another Egyptian text often cited is the Inventory Stela (sometimes called the “Stela of Khufu’s Daughter”), likely from the much later 26th Dynasty (Saite period, c. 670–525 BC). It purports to record that Khufu (Khafre’s father) found the Sphinx already buried in sand and carried out repairs to honour it. The stela even claims Khufu built a temple next to the Sphinx. If the claim is accepted at face value, it implies that the Sphinx predates Khufu, which contradicts the Khafre attribution. However, Egyptologists overwhelmingly consider the Inventory Stela to be pseudo-historical – a later fabrication or allegory, not a factual Old Kingdom record. Its style of hieroglyphic writing and the deities mentioned point to a first-millennium BC creation—likely an attempt by Saite priests to legitimise local cults by backdating them to the Old Kingdom. Even Gaston Maspero (a 19th-century Egyptologist) speculated the Inventory Stela might copy an authentic 4th Dynasty document, but this theory is viewed with strong scepticism today. In summary, apart from New Kingdom references (which already associate the statue with Khafre), no ancient inscription firmly credits any other pharaoh with building the Sphinx. The lack of Old Kingdom text is generally attributed to the monument’s unfinished state and long periods of abandonment when it was covered by desert sands.

Classical sources: Greek and Roman writers had limited knowledge of the Sphinx’s origins. Herodotus (5th century BC) notably does not mention the Sphinx in his description of Giza’s monuments, possibly because it was once again buried by his time. Later writers, like Pliny the Elder (1st century AD), did mention the Sphinx but only as a marvel; Pliny repeats a folk belief that it was a tomb of a king named “Harmachis” (a Hellenised form of Hor-em-akhet) – indicating that even in antiquity its true history was obscure. These classical anecdotes neither confirm nor refute Khafre’s involvement; they mainly underscore that the Sphinx’s origin was a mystery even to later Egyptians and Greeks, reinforcing the importance of archaeological evidence to identify its builder.

Archaeological Evidence from the Giza Plateau

The physical and archaeological context of the Sphinx strongly supports its construction during Khafre’s reign. The Sphinx is not an isolated monument—it is tightly connected to Khafre’s pyramid complex; the arrangement of causeways, temples, quarries, and the Sphinx itself all suggest a single master plan in the mid-3rd millennium BC.

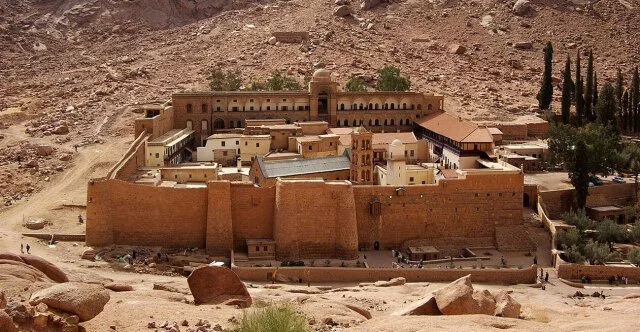

Location and Alignment: The Great Sphinx sits directly adjacent to Khafre’s Pyramid. It faces due east, situated just off the causeway that leads from Khafre’s pyramid down to what is known as the Valley Temple (a ceremonial temple near the Nile edge). In the 1850s, archaeologist Auguste Mariette excavated this Valley Temple and discovered a life-size diorite statue of Khafre within it. The presence of Khafre’s statue in situ firmly links the temple—and, by extension, the area around the Sphinx— to Khafre’s reign. Mariette also uncovered a paved causeway connecting this Valley Temple to Khafre’s upper Mortuary Temple by the pyramid, showing that the whole complex (pyramid, mortuary temple, causeway, valley temple) was designed together. The Sphinx is carved out of the bedrock immediately north of this causeway, and its enclosure forms part of the causeway’s southern wall. The arrangement suggests the Sphinx’s creation was incorporated into Khafre’s construction project – it is spatially and architecturally tied to Khafre’s pyramid layout, positioned as if to guard the causeway approach. Indeed, archaeologists have noted that the Sphinx’s location was likely chosen because a natural limestone hill there remained after quarrying blocks for the pyramids; carving it into a Sphinx made it a creative component of the site plan rather than leaving a random outcrop.

Sphinx and Temple Complex: In front of the Sphinx (to the east) lie the ruins of the so-called Sphinx Temple, discovered in 1925 by Émile Baraize. The ground plan of this Old Kingdom temple is strikingly similar to Khafre’s Valley Temple nearby. Both structures consist of large limestone core blocks with granite facing (in antiquity) and have an open central court flanked by pillars. The similarity in architectural style and the alignment of the Sphinx Temple with the Sphinx itself indicate they were part of one project. Notably, Khafre’s Mortuary Temple (by his pyramid) contains a courtyard of the same dimensions and layout as the Sphinx Temple’s court, further hinting that the same architects or pharaoh were at work. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass writes that these clues “tied the Sphinx to Khafre’s pyramid and his temples” in a single design. It appears that Khafre planned a grand ceremonial complex: a pyramid, mortuary temple, causeway, valley temple, and the Sphinx with its own temple, all interconnected.

Quarrying Evidence – Integrated Construction: Perhaps the most compelling archaeological evidence comes from stone quarry analysis. The Sphinx was carved in place from the natural bedrock, which meant a U-shaped quarry ditch was excavated around the body. In the early 1980s, Mark Lehner (an Egyptologist) and Thomas Aigner (a geologist) conducted a “stone by stone” mapping of the Sphinx and Sphinx Temple. They discovered that the huge limestone blocks removed from around the Sphinx were reused to build the Sphinx Temple itself. Many of the core blocks in the temple walls contain the same geological strata in the same sequence as the layers in the Sphinx’s body, and those layers line up perfectly from the Sphinx into the temple masonry. In other words, as ancient quarrymen carved the Sphinx out of the bedrock, they hauled the excess limestone away and immediately assembled it into the adjacent temple’s walls. Lehner and Aigner even “fingerprinted” the limestone fossils in the blocks to confirm they match the Sphinx pit layers. This is strong evidence that the Sphinx and its temple were built at the same time. Since the Valley Temple next door is attributed to Khafre (by its contents), it follows that the Sphinx and Sphinx Temple were part of Khafre’s construction efforts as well. Summarising this, the Smithsonian magazine noted: “The fossil fingerprints showed that the blocks used to build the [Sphinx] temple must have come from the ditch surrounding the Sphinx… hauled away… as the Sphinx was being carved.” This data directly ties the monument to Khafre’s reign when the quarrying for his pyramid complex was underway.

Khafre’s Statues and Sphinx Iconography: Further linking the Sphinx to Khafre is the presence of multiple Khafre statues and sphinxes in his complex. Besides the diorite Khafre statue found in the Valley Temple, archaeologists have noted there were likely sphinx statues associated with Khafre’s monuments. Inside Khafre’s Valley Temple are emplacement slots for a series of statues. According to a PBS/NOVA investigation, there were positions for four colossal sphinxes (26 ft long) – two flanking each of the temple’s two entrances. While those statues are not preserved, their existence shows that Khafre employed the sphinx motif (human-headed lion) in his building program. This aligns with the idea that the Great Sphinx – the largest sphinx of all – was carved under Khafre’s auspices as the grand centerpiece of this theme. Indeed, an encyclopedic source states: “In his time, two sphinxes 26 ft (8 m) long were constructed at each of the two entrances to [Khafre’s] temple”. Such use of sphinx imagery in Khafre’s context makes it very plausible that the giant Sphinx is Khafre’s own portrait as a guardian “lion king”.

Site Engineering Considerations: Egyptologists have also pointed out a telling piece of site engineering evidence: Khafre’s causeway has a drainage channel that runs off to the side – and it empties into the Sphinx enclosure. This would have been a bizarre design if the Sphinx (a sacred image) already occupied the hollow. Archaeologist Mark Lehner argued that the ancient builders would not direct runoff water to erode or flood an existing sacred statue’s enclosure. Instead, the causeway and its drain were likely built before the Sphinx was carved. The fact that the channel terminates where the Sphinx would later be suggests the ground was intact when the causeway was built; only afterward did Khafre’s workers cut the Sphinx out, intersecting the drain’s path. This sequencing supports Khafre’s timeline (causeway first, then Sphinx). If the Sphinx had been an older monument already present, Khafre’s engineers would have had to plan the drain differently to avoid “desecrating” the site. The integration (and slight misalignment) of these elements makes sense if all were done in Khafre’s project rather than a later pharaoh intruding on someone else’s monument.

Worker’s Cemetery and Town: In the 1990s, archaeologists (including Z. Hawass and M. Lehner) discovered a large labourer’s cemetery and a settlement southwest of the Sphinx. The cemetery held tombs of overseers and hundreds of simple graves of workers, with inscriptions and pottery dating it to the mid-4th Dynasty (Khafre’s era). Nearby, Lehner excavated the “Lost City of the Pyramid Builders,” a settlement of barracks and houses for thousands of workers, again dated to Khafre’s reign. These finds show that a massive workforce was active at Giza during Khafre’s time – presumably the crews that built his pyramid and very likely carved the Sphinx. The scale of the project (the Sphinx is 240 ft long) would have required organised labour and provisioning, which is attested by this workers’ village in Khafre’s reign. There is no evidence of a similar workforce in earlier periods at Giza, which argues against the idea of a much older Sphinx built by an earlier civilisation. The presence of bakeries, barracks, and tombs tied to Khafre’s project reinforces that all major constructions on the plateau – including the Sphinx – were achieved by the Old Kingdom state.

In sum, the archaeological evidence paints a consistent picture: the Great Sphinx forms part of Khafre’s pyramid complex, both physically and chronologically. As Dr. Hawass summarizes, “the Sphinx represents Khafre and forms an integral part of his pyramid complex”. No finds at Giza definitively contradict this – on the contrary, every major discovery (statues, temple layouts, quarry linkages, worker settlements) bolsters the Khafre attribution.

Statue of King Khafre, Mustang Joe

Stylistic and Iconographic Analysis

Stylistic and iconographic evidence also plays a role in the Sphinx debate. The statue’s appearance – its facial features, headcloth, and proportions – can be compared to other known royal sculptures to see if it matches Khafre’s known iconography.

Royal iconography of the Sphinx: The Great Sphinx is depicted wearing the royal nemes headdress (the striped cloth seen on pharaohs like Tutankhamun’s mask) and originally had the uraeus (cobra emblem) on its forehead and a ceremonial false beard (fragments of the Sphinx’s broken beard have been found in excavations). These elements mark it clearly as a representation of a pharaoh, not just a random man or deity. The nemes and beard are symbols of kingship – for instance, the famous statue “Khafre Enthroned” from Khafre’s Valley Temple shows him with the same nemes and a similar beard shape, along with a falcon god protecting his head. The fact that the Sphinx has these attributes is one reason most scholars believe it depicts a specific king – almost certainly Khafre – as opposed to being an earlier religious statue or a generic lion. The combination of a lion’s body with a king’s head itself is a powerful piece of iconography: it represents the pharaoh as a divine protector and embodiment of solar power. In the Old Kingdom, the pharaoh was often likened to a lion or to the sun god on the horizon; Khafre in particular emphasised solar connections (his pyramid aligns with the sun and he built a temple to the sun-god Re at Abu Gorab). Thus, carving his likeness onto a colossal lion facing the rising sun would fit Khafre’s ideology of kingship. The later name “Hor-em-akhet” (Horus of the Horizon) given to the Sphinx in New Kingdom times likely reflects the original intent – the pharaoh portrayed as a form of Horus guarding the horizon.

Facial features and portraits: Although the Sphinx’s face is heavily eroded, Egyptologists generally observe that its broad contours and certain details resemble Khafre’s other portraits. The face is described as having a square jaw, high cheekbones, and a distinct expression. A small ivory statue of Khufu (Khafre’s father) exists, and a number of statues of Khafre have survived – these allow comparisons. Notably, Rainer Stadelmann, a prominent Egyptologist, conducted a detailed comparison of the Sphinx’s face to known royal images. Stadelmann concluded that the Sphinx’s visage did not match Khafre as well as it matched Khufu. He pointed out that the shape of the nemes headdress on the Sphinx and the style of the attached beard were more indicative of early 4th Dynasty art (Khufu’s time) than Khafre’s. In a documentary interview, Stadelmann observed the “square face, a little bit [of a] bitter mouth, [and] protruding eyes” of the Sphinx and said “for me, [it’s] the same face” as Khufu’s statue. This led him to propose that perhaps the Sphinx was originally conceived by Khufu (and might even portray Khufu), later appropriated by Khafre. However, Stadelmann’s view is a minority position (discussed more in the next section). Most experts see the Sphinx as fitting Khafre’s visage. The consensus view is that the face is indeed Khafre’s, albeit worn. For example, the curator of the Cairo Museum describes the Sphinx as bearing Khafre’s likeness in educational materials. And the NOVA/PBS special on the Sphinx concluded unambiguously: “It is Khafre’s face that adorns the Sphinx”, acting as the protector of the king’s pyramid tomb.

It’s important to note that assessing a 4,500-year-old weathered face can be subjective. Some forensic-style studies have been attempted (in the 1990s, a police artist claimed the Sphinx’s facial proportions didn’t match Khafre, stirring publicity), but Egyptologists caution that erosion and ancient repairs make direct comparison difficult. The headdress and general stylistic program (half man, half lion, wearing royal regalia) are clearly of the Old Kingdom royal style. There were no pharaohs before the 4th Dynasty that we know of who had such iconography, which again points to Khafre’s epoch as the logical time of creation. Additionally, a fragment of the Sphinx’s beard in the British Museum shows a pleated style thought to be consistent with 4th Dynasty artistic fashion (though some argue it might be from a later restoration).

Other Sphinxes in Egyptian art: The Great Sphinx is the earliest colossal sphinx, but smaller sphinx statues do appear around that era. For example, a sphinx head of Djedefre (Khafre’s brother) was found at Abu Roash, indicating that Khafre’s contemporaries also adopted the sphinx form. By the New Kingdom, sphinx statues (often with different heads, like rams or criosphinxes) were common. The Great Sphinx likely set a prototype. Its distinctly Old Kingdom style head – the nemes and facial shape – is quite different from New Kingdom sphinxes (which often have different crowns or more exaggerated features for later kings). This stylistic context supports the view that the Great Sphinx belongs to the Old Kingdom and most likely represents Khafre.

In summary, iconography and style strongly suggest the Sphinx is a royal monument of the 4th Dynasty. The mainstream view (espoused by experts like Zahi Hawass, Mark Lehner, etc.) is that the statue’s face is meant to be Pharaoh Khafre. Hawass notes that “the Sphinx represents Khafre,” and the statue’s features – as far as we can tell – align with Khafre’s known imagery. While a few scholars have argued it might depict Khufu instead (based on subtle artistic cues)., this is not widely accepted. Most find that the balance of stylistic evidence, combined with the overwhelming archaeological context, still points to Khafre as the Sphinx’s intended identity.

Inscriptions and Epigraphic Evidence (or the Lack Thereof)

One notable aspect of the Great Sphinx is the absence of contemporary inscriptions naming it or its builder. Unlike pyramids, which often have internal worker marks or later inscriptions identifying the pharaoh, the Sphinx bears no clear ancient labels. Egyptologists have several interpretations for this silence:

Incomplete monument and cult: As mentioned, Mark Lehner’s research indicates the Sphinx’s associated temple was never finished in antiquity. Blocks were left rough, and there is scant evidence of a functioning cult (no offering tables or extensive decoration from the Old Kingdom). Lehner concludes it is “doubtful whether a cult service specific to the Sphinx was ever organised” in Khafre’s time. This could explain why Khafre left no dedicatory stela or inscription – he may have died before fully institutionalising the Sphinx’s ritual significance. The monument might have been simply one component of Khafre’s funerary complex, and once the king died, attention shifted to completing his tomb and mortuary cult. The Sphinx (lacking internal chambers) had no obvious place for an inscription to be carved, unlike a temple or tomb. Thus, no inscription explicitly says “Khafre built the Sphinx.” This gap, however, is an argument from silence and does not outweigh the other evidence tying it to Khafre.

Dream Stele (New Kingdom): By Thutmose IV’s time, the association with Khafre was apparently recorded on the Dream Stele. As noted earlier, the stele’s text includes a royal name (likely Khafre’s) in the context of the Sphinx story. Egyptologists like James Henry Breasted, when translating the stele in the 19th century, took this as confirmation that the Sphinx was believed to be “Khafre’s statue”. The Dream Stele doesn’t explicitly say “Khafre built it,” but the implication is that Thutmose IV is addressing the Sphinx as a divine image tied to Khafre’s identity or era. This is often cited as post-facto textual evidence in support of Khafre’s authorship, even though it was written 1,100 years after Khafre. The stele itself, importantly, was made of granite from Khafre’s own pyramid complex (reused lintel stone) and was positioned as if to restore or renew the Sphinx’s cult. This suggests Thutmose IV (and his priests) saw the Sphinx as an old monument worthy of restoration – consistent with it being an Old Kingdom relic of Khafre’s time. In summary, the Dream Stele associates the Sphinx with Khafre in the ancient Egyptian record.

Inventory Stela (Saite, later period): The Inventory Stela is often brought up by those questioning Khafre’s role, because it tells a differing tale – that Khufu found the Sphinx (and an associated Isis temple) already existing and decayed, and he repaired them. If true, that would mean the Sphinx predates Khufu (and thus Khafre). However, as discussed, this stela is considered historically unreliable. Its likely purpose was to boost the importance of a local shrine by connecting it to Khufu. Scholars like Selim Hassan (who excavated the Sphinx in the 1930s) and others note the stela’s content doesn’t align with Old Kingdom language or theology, and it lists deities in a way that fits the first millennium BC. Therefore, mainstream Egyptology does not accept the Inventory Stela as evidence that the Sphinx is older than Khafre – rather, they see it as later legendgizamedia.rc.fas.harvard.edu.

No Old Kingdom name: We do not know what Khafre (or his contemporaries) called the Sphinx. In contrast, Khafre’s pyramid was named (ancient name: “Wer(en)-Khafre” meaning “Khafre is Great”). The Sphinx might have simply been considered a manifestation of a god, not needing a separate name. By New Kingdom, it was called Hor-em-akhet and Bw-Ḥw (“Place of Horus”) and later still the Greeks used Harmachis. In Arab tradition, it gained the nickname Abu al-Hawl (“Father of Terror”). The lack of a known Old Kingdom name is expected if the Sphinx’s worship wasn’t fully developed then.

In essence, while no inscription from Khafre’s time explicitly says he built the Sphinx, the circumstantial epigraphic evidence (Dream Stele) supports Khafre, and no credible ancient text assigns it to anyone else. Egyptologists often point out that many Old Kingdom royal works went uninscribed (for instance, Khafre’s Valley Temple itself had no inscribed labels; its attribution is known only from context and the statue finds). The Sphinx is another such case where context must substitute for inscription. Given the strength of that context, scholars remain confident in the Khafre attribution, and they interpret the silence as a result of historical happenstance (incompletion and burial by sand) rather than evidence of a different builder.

The Great Sphinx of Giza measures 240 feet long (73 m) and stands 66 feet high (20 m), oriented on a straight west-to-east axis, Giza, Egypt. This image was first published on Flickr. Original image by eviljohnius. Uploaded by Ibolya Horváth, published on 26 October 2016.

Geological Evidence: Weathering and Age of the Sphinx

In the 1990s, the Great Sphinx became the focus of a high-profile geological debate: does the weathering and erosion on the Sphinx indicate it is far older than Khafre’s era? This question was sparked by research from outsiders to Egyptology and has since been addressed by geologists and archaeologists on both sides. The mainstream geological view aligns with the Egyptological timeline (4th Dynasty), explaining the Sphinx’s erosion within known historical and environmental conditions.

The Erosion Controversy: In 1992, Robert M. Schoch (a geologist) and John Anthony West (an independent researcher) proposed that the Sphinx’s enclosure shows heavy rainfall erosion, which could only be the result of prolonged wet climate thousands of years earlier than 2500 BC. They noted the Sphinx’s body and the walls of its pit have a “rolling,” undulating profile, with deeply weathered recesses, unlike the sharper wind-eroded tombs nearby. Schoch initially estimated the Sphinx might date to 7000–5000 BC or even earlier (circa 9000 BC in some statements) – essentially positing a lost civilisation predating dynastic Egypt. This extreme redating was and is a fringe viewpoint. It elicited strong reactions: geologist James A. Harrell noted that Schoch’s arguments were purely geological and did not account for the rich archaeological context tying the Sphinx to Khafrehallofmaat.com. To resolve this, mainstream geologists have re-examined the Sphinx’s erosion.

Mainstream geological interpretation: Studies by K. Lal Gauri (1993, 1995), James Harrell (1994), and others concluded that the observed erosion can be explained without abandoning the Old Kingdom date. Several key points from these studies:

The Giza plateau’s Mokattam limestone has layers of differing hardness. The Sphinx’s body is composed of softer marl-like layers interbedded with harder limestone. When exposed to weather, the softer layers weather more rapidly, creating recesses, while harder layers stand out in relief. This naturally yields a rounded, undulating profile over time – even under wind-driven sand erosion or limited rain. Harrell pointed out that nearby 4th Dynasty tombs (e.g., the Tomb of Debehen) at a similar elevation show flat walls but with the weaker layers beginning to recess due to wind/sand, consistent with early stages of what we see more exaggerated on the Sphinx. In short, the Sphinx’s pattern could be a result of thousands of years of slow weathering of alternating layers, not necessarily intense rainfall ages earlier.

Rainfall in Old Kingdom and later: While Egypt’s climate was largely arid by Khafre’s time, sporadic heavy rain events have occurred throughout history. W.F. Hume, a director of the Geological Survey of Egypt, documented sudden torrential rains in the desert that caused flash floods and cut deep channels in soft rock. Such events, even if rare (once a century, say), over a few millennia can contribute to significant erosion. The Sphinx enclosure may have collected rainwater runoff in rare storms, periodically washing against the walls. Moreover, right after the Old Kingdom (c. 2200 BC), Egypt’s climate did become slightly wetter for a time; and again in the early first millennium BC there were episodes of greater rainfall. These could have hastened the rounding of the Sphinx’s features. Importantly, the Sphinx has spent most of its history buried up to its neck in sand, which actually protects the lower body from wind erosion but can trap moisture against the rock. Geologists note that damp sand against limestone causes salt crystallisation that breaks down the surface.

Active weathering today: Zahi Hawass has observed that even in modern times the Sphinx’s stone is deteriorating – flakes pop off due to salt and humidity changes. Researchers agree that “the same erosion patterns cited by Schoch still continue on a daily basis” in the present climate. This undermines the notion that only a prehistoric climate could produce the observed erosion. In fact, much of the damage may have accelerated in the last millennium or two, due to the rising water table and human activity. Thus, one need not invoke 10,000 BC rainstorms – normal weathering processes in an arid environment (wind, rare rain, dew and salt) are sufficient to explain the Sphinx’s condition.

Mainstream geologists who studied the Sphinx (like Gauri et al. in Geoarchaeology 1995) concluded that the weathering is compatible with an age of ~4,500 years. For example, Gauri showed how combinations of wind erosion, wet sand, and chemical weathering could create the rounded profile in a relatively short geologic time. Lehner notes that the hardest layers (e.g., the Sphinx’s head, which is a harder limestone member) have survived almost intact except for the nose, whereas the softer body is deeply weathered – a normal differential erosion scenario. If the statue were many thousands of years older, arguably the head would also show much more extreme erosion or would have needed ancient restoration (for which there is no evidence prior to New Kingdom repairs).

To summarise the geological stance: There is no compelling geologic necessity to date the Sphinx earlier than Khafre. Egyptologist Kate Spence quipped that while the Sphinx’s erosion is “dramatic,” the leap to redate it to 7000 BC is “like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut” – unnecessary given simpler explanations (existing weathering processes and Khafre’s context suffice). Mainstream science recognizes Schoch’s observations but finds they are “amenable to an alternative interpretation… more consistent with archaeological orthodoxy.”hallofmaat.com In other words, by aligning the geological evidence with archaeological evidence, the 4th Dynasty date holds firm.

Finally, it’s worth noting that even if the erosion suggested an older date, one would then have to explain why absolutely no artefacts, tools, inscriptions, or burials from a pre-2500 BC civilisation have been found at Giza – a huge problem for fringe theories. The geological consensus therefore reinforces the archaeological timeline: the Sphinx was carved in the mid-3rd millennium BC and has been shaped by natural forces since, requiring vigilant conservation today just as in ancient times.

Mainstream Scholarly Consensus and Debates

Within the Egyptological community, the overwhelming consensus is that Khafre was the builder of the Great Sphinx. This view is supported by virtually all the leading Egyptologists and institutions: the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities (led by figures like Dr. Zahi Hawass), the American Research Center in Egypt, the Giza Plateau Mapping Project (Dr. Mark Lehner), and others have consistently attributed the Sphinx to Khafre’s reign. Hawass states plainly, “Most scholars believe, as I do, that the Sphinx represents Khafre”and was an “integral” part of his pyramid complex. Likewise, textbooks and museum exhibits identify the Sphinx as likely carved under Khafre around 2500 BC. This is sometimes called the “Khafre-Sphinx theory” (essentially the orthodox position).

However, academic discourse allows for some debate. A handful of Egyptologists have proposed variants on the attribution – notably suggesting either Khafre’s father (Khufu) or his half-brother (Djedefre) as the initiators of the Sphinx. It’s important to stress these are minority views, but since they come from credentialed scholars, they merit mention:

Rainer Stadelmann’s Khufu hypothesis: Dr. Rainer Stadelmann (former director of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo) argued that the Sphinx might have been started by Pharaoh Khufu (builder of the Great Pyramid) and only completed by Khafre or later. Stadelmann noted certain anomalies: the Sphinx’s axis is slightly off-center from Khafre’s pyramid and causeway, which he thought could imply it wasn’t originally part of Khafre’s symmetric plan. He also pointed to stylistic elements (the nemes headdress shape, and the form of the “diadem” or uraeus and beard) that he believed were more characteristic of Khufu’s time. In his view, Khufu – who had no large Sphinx of his own found – might have commissioned the statue as a guardian or as a form of the sun god for his necropolis, and Khafre later reused the idea. Stadelmann published this theory in 1999/2000, suggesting that the “Sphinx and Sphinx Temple was also built by Khufu rather than by Khafre”, essentially a Khufu origin for the Sphinx Temple that Khafre then built his causeway around. To support this, he noted that the Sphinx Temple’s architectural style has some differences from Khafre’s Valley Temple, perhaps indicating an earlier phase. He also tied in religious reasoning: Khufu’s Horus name and solar associations, and the Sphinx’s later name Hor-em-akhet (“Horus of the Horizon”), speculating that the Sphinx could have been a sun shrine created by Khufu as an embodiment of Ra-Horakhty on the horizon. Despite these arguments, most experts remained unconvinced. Zahi Hawass responded that Stadelmann’s case, while intriguing, was not compelling against the body of evidence for Khafregizamedia.rc.fas.harvard.edu. No direct evidence of Khufu at the Sphinx has surfaced – e.g., no Khufu-era tool marks or inscriptions in the Sphinx enclosure. Furthermore, Khafre’s ownership of the Valley Temple and causeway is clear, and the Sphinx fits seamlessly into that context. So Stadelmann’s hypothesis is often acknowledged in scholarly literature but usually refuted as less convincing than the orthodox view. Mark Lehner’s analysis actually allows a nugget of Stadelmann’s idea: Lehner concluded Khafre was responsible for “most of the Sphinx,” but conceded that “Khufu might have started it.”– meaning perhaps Khufu left a proto-sphinx or a shaped outcrop that Khafre later recarved. This is speculative, and Lehner emphasises Khafre’s role as primary. Essentially, even those open to Khufu’s involvement agree Khafre finished and shaped the Sphinx as we know it.

Vassil Dobrev’s Djedefre hypothesis: In the early 2000s, Dr. Vassil Dobrev of the French Archaeological Institute in Cairo announced a theory attributing the Sphinx to Djedefre, the son of Khufu and older brother of Khafre. Djedefre ruled briefly after Khufu but built his pyramid at Abu Roash, north of Giza, which later fell into ruin. Dobrev suggests that during his short reign (c. 2528–2520 BC), Djedefre created the Sphinx at Giza as a tribute to his father Khufu. His reasoning: by the time Khufu died, the people were perhaps weary from pyramid-building, so rather than another giant pyramid at Giza, Djedefre sought a different way to honour Khufu and legitimise his own rule. Propaganda motive: Dobrev argues the Sphinx would represent Khufu as a god (Ra-Horakhty), thereby reinforcing Djedefre’s connection to his illustrious father and the solar cult. Supporting clues include Djedefre’s adoption of the epithet “Son of Re” (he was the first pharaoh to put “Ra” in his royal name), indicating a strong solar focus. Also, in the boat pits around Khufu’s pyramid, some blocks bearing Djedefre’s name were found, showing Djedefre was involved in his father’s funerary arrangements. Dobrev also notes a topographical point: in ancient times, visitors coming from Memphis would approach Giza from the south. From that southern approach, the Sphinx is seen in profile in front of Khufu’s pyramid. It would present a spectacular image of a guardian watching over Khufu’s tomb, potentially fulfilling Djedefre’s goal of memorialising Khufu. This theory was publicised in media around 2004 (a UK Channel 5 documentary “Secrets of the Sphinx”) as a “solution” to the riddle. However, like Stadelmann’s idea, it has not gained wide acceptance. Egyptologist Robert Partridge responded that Dobrev’s argument, while logical, lacked hard evidence: “insufficient evidence to prove his theory”. The Giza excavations have not uncovered any inscription of Djedefre at the Sphinx, nor any direct sign of his work there. It remains possible Djedefre had some role (since the time gap between Khufu and Khafre is small – Djedefre reigned perhaps 8 years, then Khafre took over), but the mainstream still credits Khafre for actually carving the Sphinx. In effect, Dobrev’s scenario requires believing Khafre simply inherited the Sphinx from his brother – yet Khafre clearly built the temples and causeway around it. It’s more parsimonious that Khafre did the whole project. Thus, Dobrev’s theory is seen as an interesting but unproven alternative within academic circles.

Beyond Stadelmann and Dobrev, no other mainstream Egyptologist has a serious published theory assigning the Sphinx to another pharaoh. George Reisner, who excavated at Giza in the early 20th century, briefly wondered if Djedefre could have started it (he doubted Djedefre’s character and thought him an usurper), but Reisner ultimately leaned to Khafre like others. Selim Hassan’s definitive 1940s study of the Sphinx concludes with Khafre. Scholars like I.E.S. Edwards, Ahmed Fakhry, and more recently Miroslav Verner and Mark Lehner have all written that Khafre is the builder. Jane A. Hill and Catharine Roehrig, in museum catalogs, describe the Sphinx as Khafre’s image. In sum, the majority view within Egyptology has remained stable for over a century – Khafre, circa 2500 BC, is seen as responsible.

It’s telling that even the proponents of alternative attributions (Khufu or Djedefre) still place the Sphinx firmly in the 4th Dynasty, only a generation or so away from Khafre. There is no credible academic suggestion that it comes from a radically earlier time or a different civilization. This brings us to the fringe theories, which venture far outside the mainstream and propose extreme chronologies or exotic builders.

Alternative and Fringe Theories – Comparison to Consensus

For completeness, we briefly outline the alternative or fringe ideas about the Sphinx’s origins, and how they contrast with the mainstream consensus:

Pre-Dynastic / “Atlantean” Theories: Inspired by the erosion debate and legends, some have claimed the Sphinx is thousands of years older than Egypt’s Old Kingdom. Dates of c. 10,000 BC (the end of the last Ice Age) are often thrown about, linking the Sphinx to hypothetical lost civilisations. This idea gained traction through the work of John Anthony West and Robert Schoch, who, as noted, argued for a construction possibly between 7000–9000 BC based on presumed water erosion. Others have extended this to even earlier, tying it to the legend of Atlantis (notably, Edgar Cayce prophesied that the Sphinx was built in 10,500 BC by Atlanteans and that a “Hall of Records” lies beneath it). These theories are not supported by physical evidence. Mainstream archaeologists point out that no trace of high civilisation in Egypt (or elsewhere) exists from that period – the Neolithic peoples of 7000 BC left primitive dwellings and small settlements, nothing on the scale of the Sphinx. The fringe proponents often circumvent this by invoking aliens or lost continents, which places their claims well outside scientific plausibility. As a result, Egyptologists do not take these ideas seriously. Hawass has openly derided the more extreme proponents as “pyramidiots” for advancing wild claims (such as secret chambers and alien technology) that distract from real research. The consensus is that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and so far the fringe ideas have produced no verifiable evidence – only reinterpretations of the weathering (addressed above) and imaginative speculation. In fact, extensive surveys (seismic, drilling) around the Sphinx have not revealed any mysterious pre-dynastic chambers or hidden archives – only natural fissures and some small Old Kingdom tunnels used by treasure hunters.

Cultural context vs. lost civilisation: Mainstream scholars emphasise how well the Sphinx fits into the context of Khafre’s 4th Dynasty court – artistically, religiously, and logistically. By contrast, placing it in 10,000 BC creates an inexplicable gap: one would have to believe that an advanced society sculpted the Sphinx (and perhaps began carving on the Giza site), and then all knowledge and progress vanished, only for Egyptians 6,000 years later to coincidentally build their pyramids right next to it. This scenario is seen as vastly less probable than the straightforward one: the Old Kingdom Egyptians themselves, whose ability to build pyramids and statues is well documented, carved the Sphinx. As geologist Harrell put it, the aim is to find an interpretation “more consistent with the archaeological orthodoxy”hallofmaat.com – in other words, one that doesn’t require rewriting the entire history of civilisation. The orthodox view passes this test elegantly, whereas the fringe view forces a radical rewrite with no corroborating data.

Reception of fringe theories: While fringe ideas get media attention, they have not penetrated academic discourse except as a foil to be refuted. For instance, in a 2017 review, the A.R.E. (Edgar Cayce’s foundation) still promotes the notion of a pre-10,000 BC Sphinx, but Egyptologists remain unmoved. Mark Lehner is a particularly interesting case: he originally went to Egypt as a young man funded by Cayce’s organisation, curious about the Hall of Records prophecy. However, after years of empirical study mapping the Sphinx and excavating around it, Lehner became a staunch defender of the orthodox view. He found nothing to suggest a lost civilisation and everything to suggest an Old Kingdom context. This transformation – from someone open to alternative ideas to a scientist persuaded by evidence – underscores how powerful the evidence for Khafre is. Lehner now works closely with Hawass and others to conserve the Sphinx and explore the Giza plateau within the framework of known history.

In comparison to these fringe notions, the mainstream consensus appears exceedingly well-grounded. It does not require any unknown peoples or drastic revision of timelines. It attributes the Sphinx to the same culture that undeniably built the surrounding pyramids and temples. As one encyclopedia entry succinctly put it: “Most archaeologists believe that the Sphinx was constructed about 4,500 years ago during the reign of Khafre… [Fringe] ideas are regarded with disbelief and derision by most mainstream scholars.”. The contrast could not be more stark – virtually all qualified Egyptologists support the Khafre attribution (with only slight internal debate as to maybe Khufu or Djedefre’s roles), whereas the ideas of extreme antiquity come from outside the field and remain unsubstantiated.

Conclusion

After examining the full range of evidence, the mainstream Egyptological consensus remains that the Great Sphinx was built in the mid-3rd millennium BC for Pharaoh Khafre. This conclusion is supported by a convergence of archaeological data (the Sphinx’s alignment and construction interlocks with Khafre’s pyramid complex, and material from its quarry was used in Khafre’s temples), iconographic analysis (the Sphinx’s royal visage and regalia are consistent with Khafre’s other statues and with Old Kingdom royal art), and geological assessments (the weathering is explicable over 4,500 years and does not necessitate a dramatically earlier date). Crucially, no evidence from antiquity crediting another builder has stood up to scrutiny – later Egyptian records like the Dream Stele in fact reinforce Khafre’s connection, and the lack of an Old Kingdom inscription is reasonably explained by the monument’s context and later history.

Within academia, the Sphinx’s attribution is not a source of major controversy. A majority of Egyptologists echo the view of Hawass and Lehner that Khafre commissioned the Sphinx as part of his mortuary complex. A few scholarly proposals (Stadelmann’s and Dobrev’s) have suggested Khafre’s immediate relatives as alternatives, but those remain speculative and have not overturned the Khafre model. In each case, those hypotheses still keep the Sphinx within the 4th Dynasty royal family, essentially affirming that it was a product of the same high civilisation that built the Pyramids.

In contrast, alternative theories that place the Sphinx in a long-lost epoch or attribute it to non-Egyptian sources are not supported by credible evidence and are rejected by experts. The academic consensus is that such ideas, while popular in pseudo-archaeology circles, do not change the fundamental fact that the Sphinx is an Old Kingdom creation – in all likelihood, the work of King Khafre’s artisans. As the Nova documentary concluded: “It is Khafre’s face that adorns the Sphinx, which [stood as protector of] the mummified king as he traveled toward the pyramid, following the path of the sun”. In the eyes of modern Egyptology, the Great Sphinx of Giza is thus understood as Khafre’s enduring legacy – a colossal guardian statue symbolizing royal power and the divine sun on the Giza plateau, built circa 2500 BC and contemplated ever since by those who seek to unravel its ancient riddle.

Sources: The conclusions above draw on the research and writings of numerous Egyptologists and geologists, including M. Lehner, Z. Hawass, R. Stadelmanngizamedia.rc.fas.harvard.edu, V. Dobrev, J. A. Harrellhallofmaat.com, K. L. Gauri, and others, as well as translations of ancient texts like the Dream Stele. These experts and sources collectively affirm the attribution of the Sphinx to Khafre and provide a multifaceted body of evidence in its favor, as detailed in the discussion above. The mainstream view remains robust, with leading Egyptological institutions continuing to uphold Khafre as the builder of the Great Sphinx of Giza.

References

Lehner, Mark. The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. Thames & Hudson, 1997.

Hawass, Zahi. The Secrets of the Sphinx: Restoration Past and Present. The American University in Cairo Press, 1998.

Lehner, Mark. The Archaeology of an Image: The Great Sphinx of Giza. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1991.

Stadelmann, Rainer. “Die große Sphinx von Giza.” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1991.

Schoch, Robert M. “Redating the Great Sphinx of Giza.” Geoarchaeology, vol. 8, no. 6, 1993, pp. 427–439.

Gauri, K. Lal, et al. “Geologic Weathering and the Age of the Sphinx.” Geoarchaeology, vol. 10, no. 2, 1995, pp. 119–133.

Harrell, James A. “The Great Sphinx Controversy.” University of Alabama Geology Papers, 1994.

Dream Stele of Thutmose IV (Translation and Commentary). UCL Digital Egypt Project.

Verner, Miroslav. The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove Press, 2001.

National Geographic Special: "Riddles of the Sphinx". National Geographic Society, 1998.

Lehner, Mark. The Giza Plateau Mapping Project: Project History and Overview. Ancient Egypt Research Associates.

Hassan, Selim. The Sphinx: Its History in the Light of Recent Excavations. Cairo: Government Press, 1949.

Reisner, George A. A History of the Giza Necropolis, Volume 1. University of Chicago Press, 1942.

PBS NOVA Documentary: "Secrets of the Sphinx". PBS, 1997.