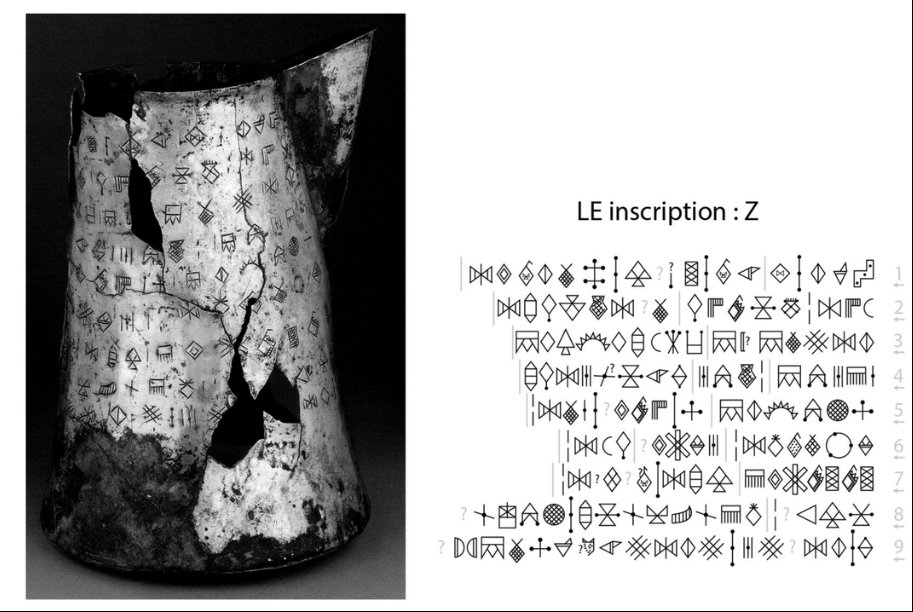

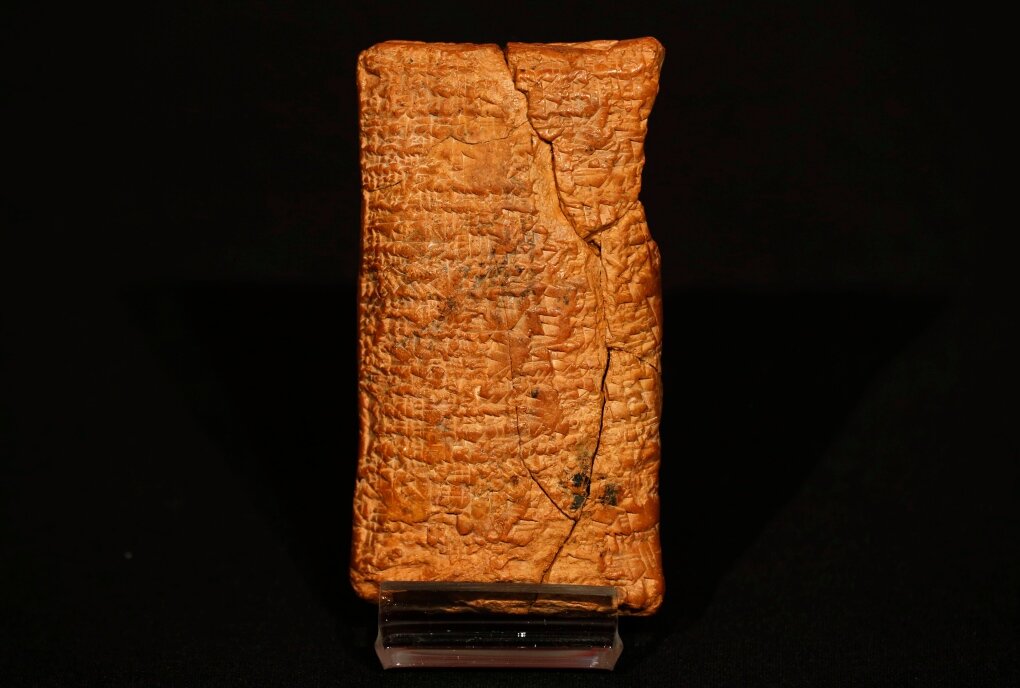

A tablet was found engraved with the measurements of a piece of land, calculated using trigonometric methods and Pythagorean triples: it is the oldest testimony of applied geometry that we know of

(Immagine: UNSW Sydney)

A tablet demonstrates how the Babylonians knew the Pythagorean theorem before Pythagoras. The measurements of a plot of land are engraved on the tablet, calculated with trigonometric methods and Pythagorean triples: this is the oldest evidence of geometry ever discovered.

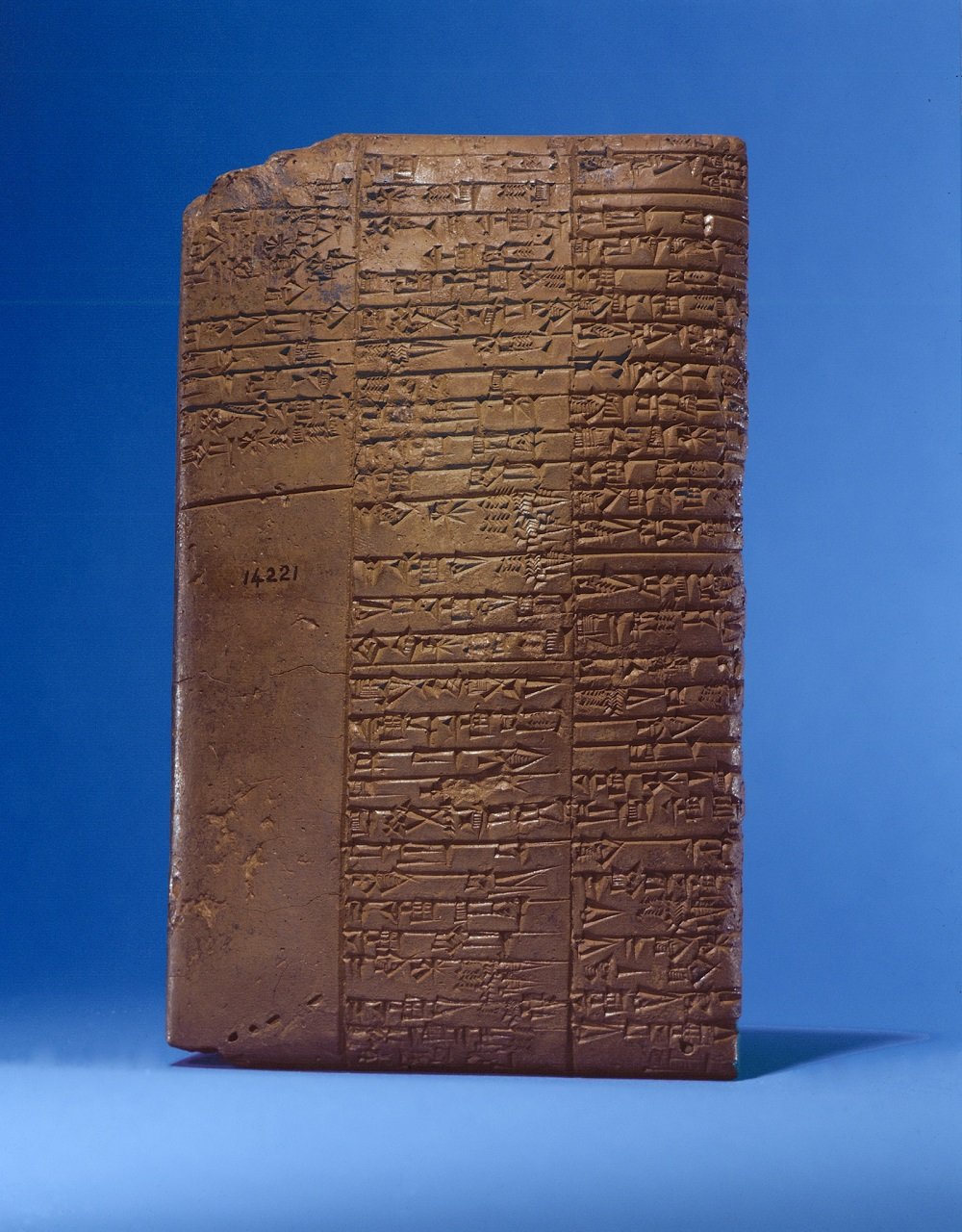

When four thousand years ago a Babylonian surveyor engraved the boundaries of some plots of land on a tablet, he probably did not imagine that his work was destined to upset the archeology of the future.

Analyzing the tablet preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, Daniel Mansfield, a mathematician from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, has in fact discovered how the ancient Mesopotamian peoples knew the Pythagorean Theorem, before Pythagoras himself.

"What I transcribed on the clay tablet, proves that the ancient Babylonians knew many basic notions of geometry, including those related to the making of right-angled triangles by applying concepts to practical problems." explains Mansfield.

On Si427 (name given to the tablet) the engravings of cuneiform characters were made which undoubtedly correspond to a long series of Pythagorean triples. The ancient surveyor had transcribed the calculations necessary to divide a plot of land by dividing it into rectangles with a precision that according to the scientist leaves no room for doubt:

The rectangles are precise: the surveyor calculated them through the Pythagorean triples: 3, 4 , 5; 8, 15, 17; 5, 12, 13. From the characteristics of the tablet, moreover, we understand how man made the engraving 'in real time', tracing the lines on the clay while he was on the ground.

But one last aspect still remains to be deciphered: the presence of a number with a sexagesimal basis, 25:29, still without any interpretation. It could be the sequence of a calculation or the area of some other terrain; but, for now, it still remains a mystery.