The term Panhellenic means “all-Greek,” reflecting a vision of unity among the often fractious city-states of ancient Greece. Throughout classical antiquity, Greeks shared a common language, religion, and cultural heritage, yet political unity was rare, due to the city-state as a political and social formation system. The concept of a Panhellenic League – an alliance embracing all Hellenes – evolved over time as circumstances compelled cooperation. From the existential threat of the Persian invasions to the grand ambitions of Macedonian kings, the ideal of Greek unity was invoked to rally support and legitimize authority. This article traces the development of the Panhellenic ideal from its early manifestation during the Persian Wars, through Philip II’s unification of Greece, to Alexander the Great’s use of Panhellenism – notably exemplified by the Priene Inscription. It also compares these efforts to later Hellenistic leagues (Aetolian and Achaean), examining how shared culture, religion, and alliances fostered unity and continuity in the Greek world.

Panhellenic Unity in the Persian Wars

In the face of Persia’s massive invasion led by King Xerxes (480–479 BC), the Greeks for the first time formed a broad coalition to defend their homeland. In 481 BC, delegates from numerous city-states met at a Congress at the Isthmus of Corinth, setting aside rivalries to forge a Hellenic League against the “barbarian” invader. Thirty-one states – including Athens, Sparta, Corinth, Thebes, and others – pledged a common cause. Long-standing feuds were momentarily buried as they agreed to coordinate strategy and pool resources under Sparta’s leadership. This unprecedented alliance testified to a growing awareness of a shared Hellenic identity transcending individual polis interests. They swore oaths (reportedly “by Zeus, Poseidon and other gods”) to punish any Greek city that medized (sided with Persia) and to honor their mutual defense pact. Religious tradition buttressed this unity: for example, the league declared that if any Greek traitor aided Persia, one-tenth of that offender’s wealth would be dedicated to Apollo’s oracle at Delphi as punishment – a solemn spiritual deterrent. The oracle of Delphi itself played a unifying role, as Greeks jointly consulted its prophecies for guidance on how to survive the onslaught.

Though Greek unity was far from complete (many states remained neutral or under Persian sway, and Sparta and Athens still squabbled over navy command), the alliance achieved remarkable success. United Greek forces won decisive victories at Salamis and Plataea, halting the Persian aggression. In the aftermath, the Greeks commemorated their collective triumph in ways that emphasized Panhellenic solidarity. At Delphi, they erected the famous Serpent Column – a bronze tripod of intertwined serpents – inscribed with the names of all the Greek cities that stood together against Persia. This monument, dedicated to Apollo, symbolized how shared myths, gods, and resolve had bound the Hellenes in their hour of need. Similarly, festivals like the Olympic Games, which had long been open to all Greeks, took on added significance after the war as celebrations of a common Greek victory. The Persian Wars thus ignited the “first seeds of Panhellenism”, proving that when faced with a common enemy and inspired by common culture, the disparate Greeks could act as one people. The ideal of Hellenic unity — however fleeting in practice — had been vividly realized and would be remembered in later generations as a golden example of what the Greeks could accomplish together.

SerpentColumn, Delphi

Philip II and the Panhellenic Ideal

In the fourth century BC, the Greek city-states returned to internecine conflicts and power struggles. Yet the Panhellenic ideal did not disappear; instead, it was revived as a compelling political vision by thinkers like Isocrates and eventually put into action by Philip II of Macedon. Isocrates, an Athenian orator, watched decades of warfare between Greek poleis (notably the Peloponnesian War and its aftermath) and concluded that only a unified Greek effort against a foreign foe could end the cycle of chaos. In 380 BC, he wrote Panegyricus, urging Greeks to reconcile and jointly campaign against Persia. Later, in 346 BC, Isocrates penned an open letter To Philip, imploring the rising Macedonian king to assume leadership of a pan-Hellenic crusade. He argued that Greece’s infighting and the poverty of many Greeks could be solved by homonoia (concord) under a single leader and a common enterprise of conquest. Philip was to “unite the Greeks under his leadership in a crusade against Persia,” a radical proposal at the time. The idea was that by rallying all Hellenes to avenge the Persian wars and liberate Greek cities in Asia, Philip would both stop the fratricidal Greek wars and channel Greece’s energies outward. That a prominent Athenian intellectual would call on a Macedonian king to save Greece underscored the desperate straits of the divided city-states – and also heralded a new reality in which Macedon had become a powerful part of the Greek world.

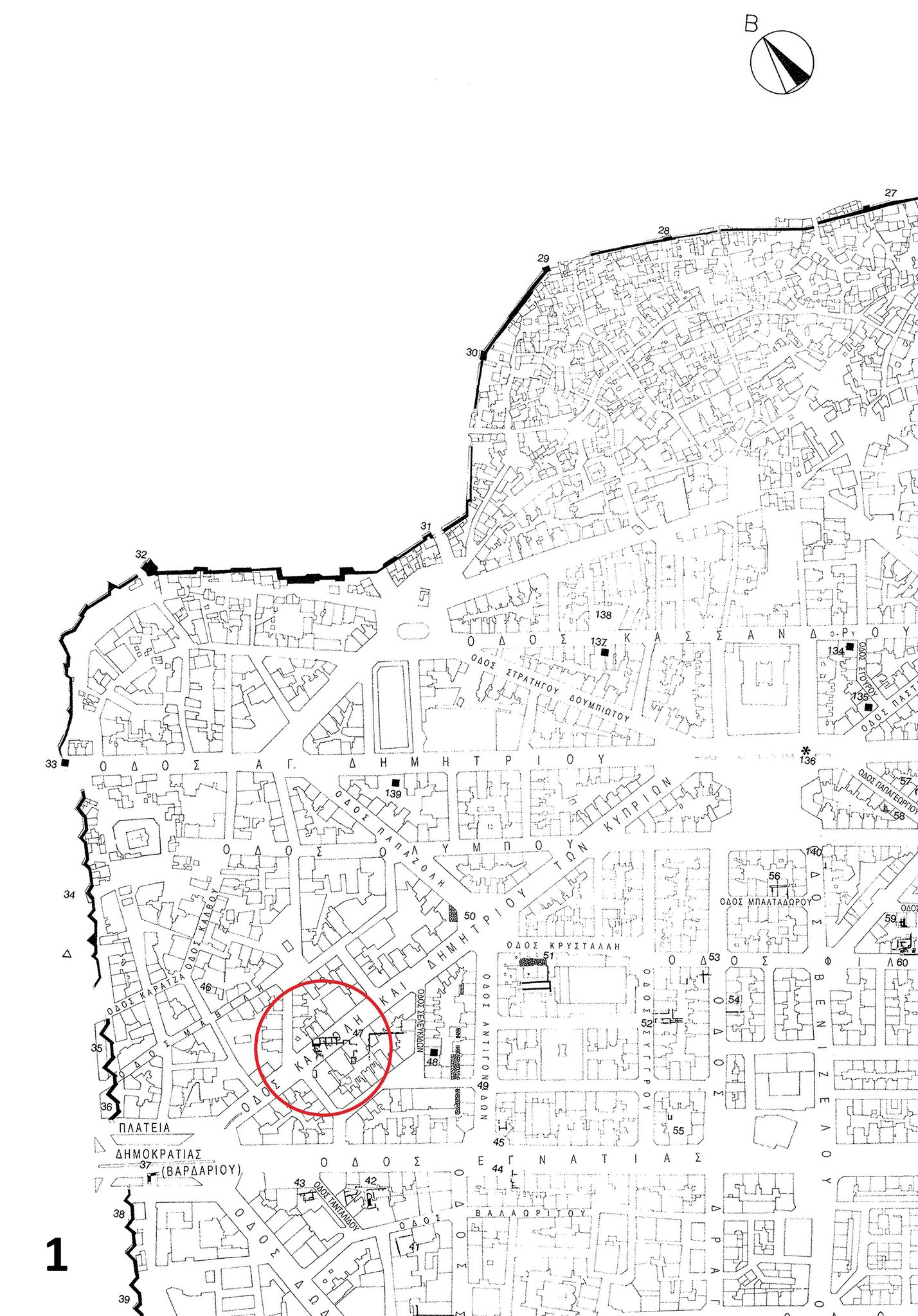

Philip II proved receptive to this Panhellenic platform, though certainly his own imperial ambitions were at play. In 338 BC, after decisively defeating an alliance of southern Greek states at the Battle of Chaeronea, Philip positioned himself as the hegemon (leader) of Greece. The next year he organized the League of Corinth (also known simply as the “Hellenic League”), a federation of Greek city-states under Macedonian leadership. For the first time in history, virtually all of Greece (with the notable exception of Sparta, which initially refused to join) was politically united in a single confederation. At the league’s inaugural council in Corinth, delegates from each member state (elected in proportion to their military strength) agreed to a Common Peace among Greeks and officially declared war on the Persian Empire. Philip was appointed strategos autokrator (supreme commander) of this Panhellenic war of revenge. The league’s charter invoked the memory of Xerxes’ invasion and the desecration of Greek temples, framing the coming campaign as righteous retribution and a fulfillment of Greece’s age-old struggle against Asiatic despotism. By harnessing Greek resentment of Persia and the nostalgia for unity, Philip endowed his imperial project with an ideological cloak of Panhellenism.

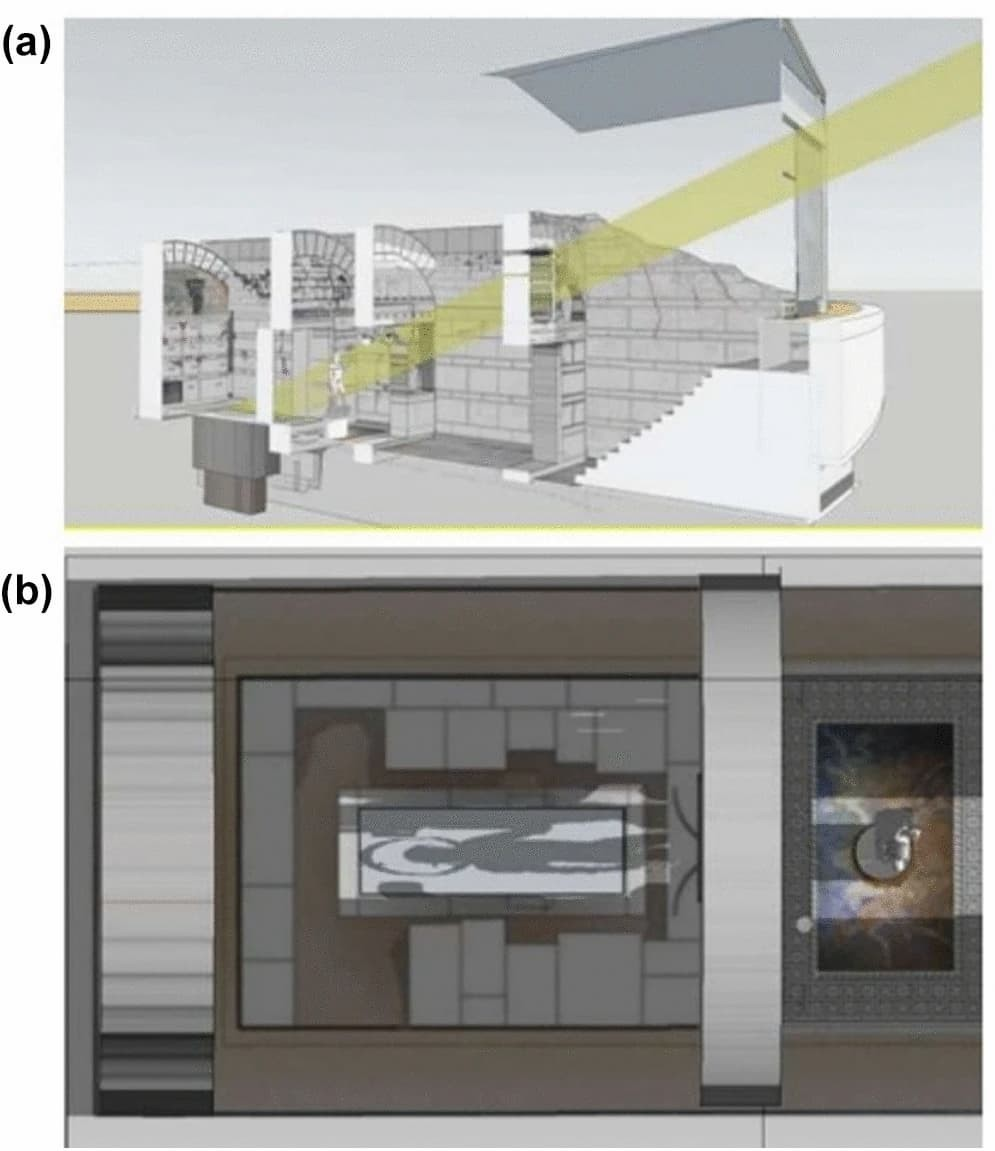

Religion and shared culture were important in legitimizing Philip’s leadership. The Macedonian kings themselves had long claimed Greek ancestry (Philip traced his lineage to Heracles) and participated in Panhellenic institutions to prove their Hellenic identity. Philip famously competed in the Olympic Games – winning the horse race in 356 BC – and sponsored lavish religious dedications. After Chaeronea, he erected the Philippeion at Olympia, a grand circular shrine within the sacred Altis precinct. Ostensibly dedicated to Zeus, it housed gold-and-ivory statues of Philip, his queen Olympias, and their son Alexander (as well as Philip’s parents), effectively placing his own dynasty among the gods and heroes in a Panhellenic sanctuary. This striking commemoration sent a clear message: Macedon was now a principal defender of Greece, and Philip’s family shared in the divine favor that traditionally smiled upon Hellenic victors. By honoring Zeus at Olympia and presenting himself as a pious benefactor, Philip reinforced his appeal to Greek sentiment. He also leveraged the Amphictyonic Council at Delphi – intervening in the Fourth Sacred War (naming himself protector of Apollo’s shrine) – to further cast himself as the champion of Greek religion and stability. In these ways, Philip II wove together military might, diplomacy, and cultural patronage to make the Panhellenic ideal a reality under his hegemony.

Alexander the Great and the Panhellenic Ideal

Philip’s assassination in 336 BC briefly threatened the new league, but his twenty-year-old son Alexander III (the Great) quickly secured Macedonian power and was acclaimed as Philip’s successor in the Panhellenic crusade. Alexander inherited both the military apparatus of the league and its ideological mission. In 334 BC, he crossed the Hellespont into Asia as the elected hegemon of the Greeks, proclaiming himself leader of a united Hellenic invasion to “take revenge” for the Persian invasions of generations past. Early in the campaign, Alexander took deliberate steps to emphasize that he fought on behalf of all Greece (Sparta again excepted) and under the auspices of the Greek gods. For example, after winning the Battle of the Granicus (334 BC) – his first major victory against the Persians – Alexander sent 300 suits of captured Persian armor as a dedication to Athena on the Acropolis of Athens. Along with this offering, he ordered a bold inscription: “Alexander, son of Philip, and the Greeks – except the Lacedaemonians – dedicate these spoils from the barbarians of Asia.” This dramatic gesture served multiple purposes. It explicitly linked Alexander with the collective Greek effort (“Alexander… and the Greeks”), pointedly snubbed Sparta for its absence, and celebrated vengeance for the impieties of 480 BC (the armor hung in Athens as proof that the sack of the Acropolis had been avenged). By dedicating enemy spoils to Athena, Alexander cast himself as the pious avenger of the desecrated Greek gods. At the same time, as one modern historian noted, he was shrewdly “emphasizing the usually denied ‘Greekness’ of the Macedonians,” reminding all that Macedon now stood at the forefront of Hellas.

Alexander’s conduct during his campaign continued to invoke Panhellenic traditions to legitimize his expanding rule. He made a point of honoring the great Panhellenic sanctuaries and heroes: for instance, detouring to Troy to pay homage to Achilles (his legendary ancestor), dedicating a temple to Athena there, and reportedly running naked around Achilles’ tomb in symbolic respect. He visited Delphi before setting out, seeking a blessing (though the Pythia was initially reluctant to prophesize, Alexander boldly grabbed her until she exclaimed “My son, you are invincible!” – which he took as the oracle he wanted). After each major victory, Alexander sent a portion of the spoils to Greek cities and temples: to Delphi, to Olympia, to Dion (in Macedon, but a Panhellenic religious center for Zeus) and elsewhere. These acts reinforced his image as protector of the Greek faith and avenger of Persian sacrilege. Indeed, when he finally seized and burned the Persian capital Persepolis in 330 BC, contemporaries viewed it as retribution for Xerxes’ burning of Athens’ temples 150 years earlier – a tit-for-tat justice completed by the Panhellenic champion. By invoking the memory of the Persian Wars and continuously dedicating victories to the gods, Alexander maintained Greek goodwill and participation (at least nominally) in his war of conquest, even as his army pushed far beyond the original objectives.

Alexander grabs Pythia and drags her to the Apollo shrine to receive the oracle, by Louis Jean Francois Lagrenée. Public Domain

Later Hellenistic Leagues and the Legacy of Panhellenism

After Alexander’s untimely death in 323 BC, his empire fragmented and the direct political unity of the Greeks under a single hegemon was short-lived. Yet the ideal of Panhellenic unity and shared identity did not vanish. During the Hellenistic period (3rd–2nd centuries BC), new federations of Greek city-states emerged, most notably the Aetolian League and the Achaean League. These leagues, though regional rather than pan–Greek in scope, drew inspiration from earlier Greek alliances and maintained important aspects of cultural continuity.

The Aetolian League rose to prominence in Central Greece, originally a union of the Aetolian communities that expanded to include many other cities. It was a federal state (koinon) with its own assemblies and magistrates, demonstrating that Greeks could form a broader political structure while preserving local autonomy. The Aetolians, proud of their rugged independence, actively invoked Panhellenic themes to boost their standing. In 279 BC, when a horde of Gauls (Galatians) invaded Greece and threatened Delphi, the Aetolian League took the lead in defending the sacred site. The Gauls were repelled, and this feat was celebrated across Greece as a deliverance akin to the Persian War of old – Polybius even ranked it alongside the victories over Persia, and Pausanias later called the Gallic threat the greatest peril Greece had faced since Xerxes. In gratitude for saving Apollo’s sanctuary, the Delphic Amphictyonic Council admitted the Aetolian League as a member and granted it a place of honor in overseeing Delphi. The Aetolians then organized the Soteria (“Deliverance”) festival at Delphi, a new Panhellenic festival (with athletic and musical contests) commemorating the Greek victory over the barbarians. This was a deliberate echo of earlier Panhellenic games and helped project the Aetolians as inheritors of the legacy of Greek unity. Through their league, they championed themselves as protectors of Hellenism – even as they also used the league for expansion and power politics. Culturally, the Aetolian League’s prominence at Delphi and its festival of Soteria show a continuity of Panhellenic religious tradition: Greek states still came together for common worship and celebration of collective victories, now under Aetolia’s auspices.

The Achaean League, based in the Peloponnese, likewise provides an example of Greeks uniting in a federal structure with cultural cohesion. Revived in 280 BC, the Achaean League eventually bound together a dozen or more city-states including not just the Achaean heartland but cities like Corinth, Megalopolis, Argos, and others. It had a constitution with a federal assembly and annually elected strategos (general), pointing to a sophisticated attempt at shared governance among formerly independent cities. The league is often studied as an early model of federalism, demonstrating “how city-states could unite under a common political structure while retaining local autonomy”. Under dynamic leaders such as Aratus of Sicyon and later Philopoemen, the Achaean League not only fought wars (against Spartan kings and Macedonian interference) but also fostered a sense of collective identity among its members. They issued common coinage and coordinated policies, projecting an image of a unified Achaean state. Culturally, the member cities shared in religious festivals and traditions; for instance, the league likely sponsored games and observed common rituals (the Achaean assembly met at the sanctuary of Zeus Homarios at Aegium in early years, indicating a religious element to their unity). The League’s cultural contributions included economic and social integration of the Peloponnese and “fostering a sense of shared identity and cooperation among its member cities”. In many ways, the Achaean League attempted to revive the cooperative spirit of the Hellenic League, though on a regional scale and without a single monarch.

Despite the successes of these leagues in creating pockets of unity, they also highlight the limits of the Panhellenic ideal in an era dominated by powerful kingdoms and, eventually, Rome. The Aetolian and Achaean Leagues sometimes allied but often quarreled, and both leagues clashed with the Macedonian kings (and later with Rome) in struggles for power. Unlike the united front of 480 BC or the Macedonian-led league of Philip and Alexander, the Hellenistic leagues were parallel regional alliances – a testament to Greek resilience in self-organization, but also a sign that Greece remained politically fragmented. Even so, the endurance of these federations into the 2nd century BC demonstrated a continuity of the Panhellenic idea: the notion that Greeks were one people and should band together for common causes did not die. Members of the Achaean League, for example, saw themselves not just as citizens of their city but also as collectively “Achaeans,” and even used the league to negotiate as a single entity with foreign powers, much as a Panhellenic union might. In 146 BC, the Achaean League made a final, doomed stand against Rome in the Achaean War, a last echo of unified Greek resistance; its defeat and the sack of Corinth symbolically marked the end of Greek political independence. Yet even under Roman rule, the cultural concept of Panhellenism persisted – centuries later, the Roman Emperor Hadrian would establish a “Panhellenion” league of cities to hark back to the classical ideal of a unified Greece.

Conclusion

From the Persian Wars through the Hellenistic age, the Panhellenic ideal evolved in response to the needs of the time. Initially an ad hoc alliance for survival, it became an aspirational ideology used by leaders like Philip II and Alexander to legitimize conquest and empire-building as a form of collective Greek enterprise. Shared elements of culture and religion – common gods, sanctuaries, oracles, athletic games, heroic legends, and the age-old dichotomy of “Greek vs. barbarian” – were the glue that held this ideal together. These factors provided a sense of brotherhood among Greeks, even when political reality fell short of complete unity. Alexander the Great deftly leveraged Panhellenic traditions, from dedicating temples and treasures to Greek gods to guaranteeing the freedoms of Greek cities, thereby casting himself as the culmination of the Panhellenic dream of unity and revenge against Persia. The Priene Inscription is a tangible testament to how Alexander melded piety and policy to appeal to Greek sentiment – dedicating a temple to Athena and at the same time affirming his role as protector of Greek liberties.

The later federations of the Aetolians and Achaeans carried the torch of Greek unity in altered form, preserving the notion that Greeks could and should govern themselves cooperatively. While they never united all of Hellas, these leagues maintained cultural continuity with the Panhellenic ideal through federal institutions and the defense of common interests (such as safeguarding Delphi or resisting tyranny). In sum, the Panhellenic League was not a single continuous entity but rather a recurring vision – one that manifested in different guises from the stand at Thermopylae to the halls of Corinth, from Alexander’s edicts to the councils of the Achaean League. This vision of Greek unity grounded in shared heritage proved powerful and enduring, leaving a legacy that would inspire leaders and writers for generations and become an integral part of how the Greeks remembered their collective past.

References

Warfare History Network – Defending the Pass at the Battle of Thermopylae.

Sheldon, Natasha. The Temenos of Apollo, Delphi. History & Archaeology Online (2021).

Thomas R. Martin – An Overview of Classical Greek History from Mycenae to Alexander, Ch. 15, Sec. 19: “Isocrates on Panhellenism.”

Alexander’s Triumph at Granicus, Warfare History Network.