Recent archaeological discoveries in Pompeii offer poignant insight into the final moments of four individuals as Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD—an eruption that buried the ancient Roman city under ash and pumice, freezing a tragic moment in time.

A City Forever Marked by Tragedy and Beauty

Pompeii, once a thriving and vibrant city, has long captivated archaeologists and historians alike. While the eruption brought widespread destruction and death, it also preserved a remarkably vivid snapshot of daily life in the Roman Empire.

New findings continue to unveil untold stories—shedding light not only on the lifestyles of its people but also on the desperate actions they took in their final hours.

A Desperate Attempt to Survive

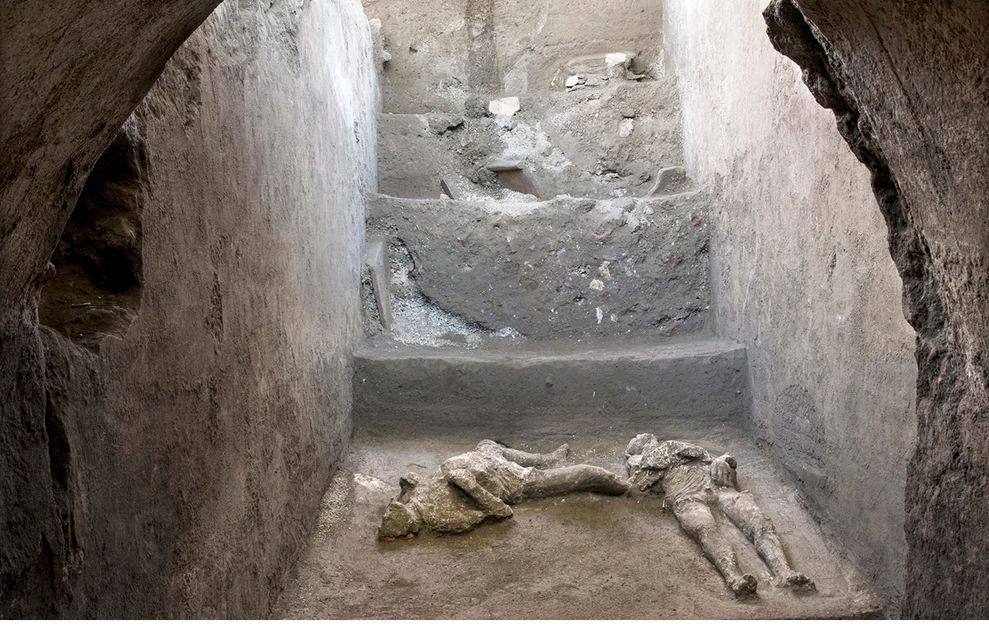

Archaeologists have uncovered compelling evidence that four people—including a child—tried to barricade themselves inside a bedroom using furniture in a last-ditch effort to protect themselves from the volcanic eruption. This haunting discovery was made in what is now called the “House of the Painters at Work,” named after a mythological fresco found inside.

The remains were found not in the room they sealed, but in an adjacent reception hall. According to research published in the E-Journal of the Pompeii Excavations, the group may have initially sought shelter in the bedroom, blocking the door with a bed, only to later try to flee when the situation worsened.

Director of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, explained that pyroclastic surges—fast-moving clouds of superheated gas and ash—swept through the city, likely sealing the fate of the trapped individuals. These surges filled buildings almost instantly, turning homes into tombs.

A Home Frozen in Time

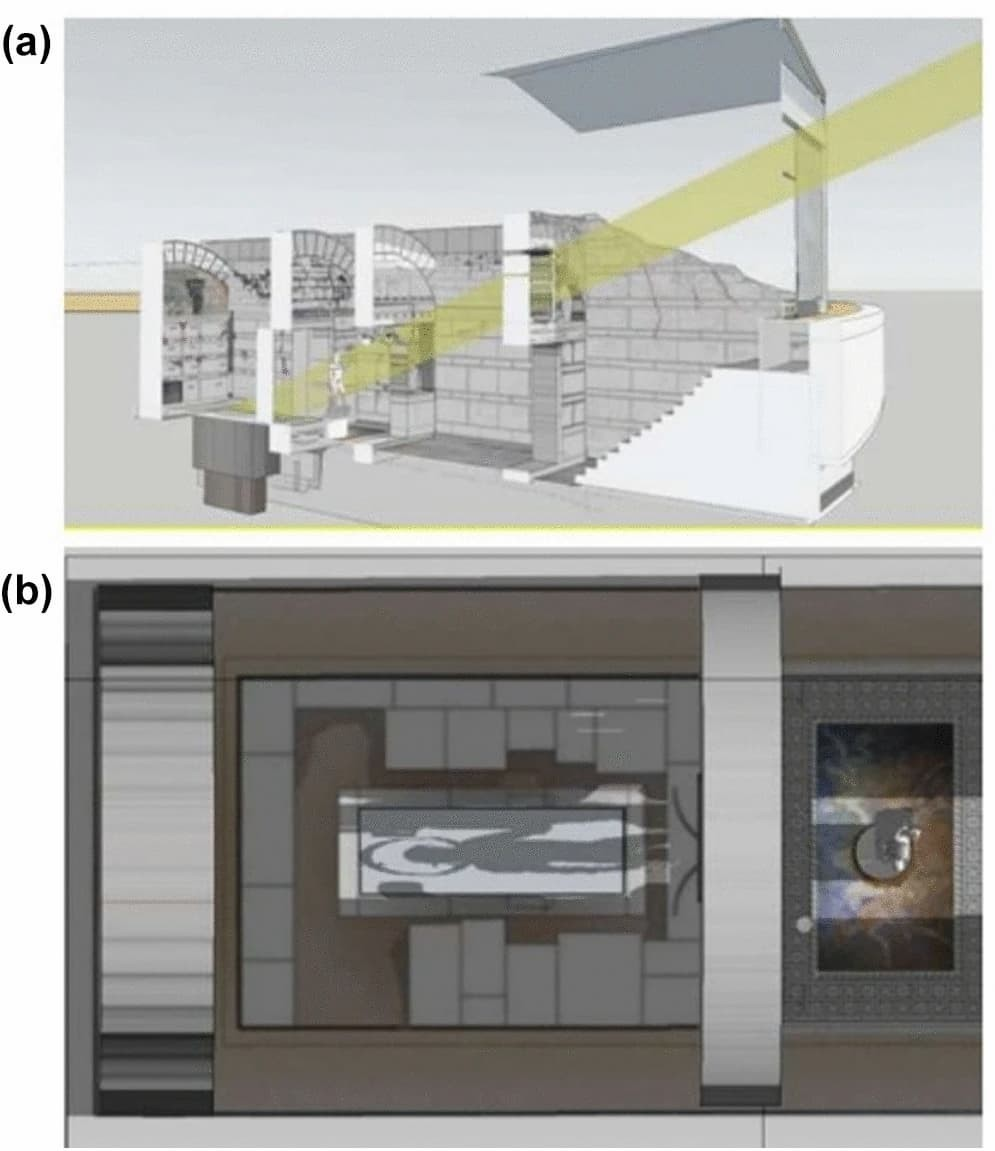

The team partially excavated the house in 2018 and 2019 but resumed investigations more recently to prepare the site for public display. In the course of their work, they uncovered about a third of the building.

The house was undergoing renovations at the time of the eruption, with evidence of removed thresholds, unfinished decorations, and partially dismantled walls. Yet it was still richly adorned, filled with refined objects and in active use—a poignant reminder of how suddenly life came to a halt.

Among the artifacts found were:

A bronze bulla, an amulet typically worn by boys until adulthood

Amphorae stored in a basement pantry, some containing garum, a pungent fermented fish sauce common in Roman cuisine

A set of elegant bronze vessels, including a shell-shaped cup, a ladle, a basket-shaped container, and a single-handled jug

“Every house in Pompeii tells a unique story,” said Zuchtriegel. “These objects speak not only to daily life but also to the trauma of sudden loss.”

When Myth Meets Reality

One of the home’s frescoes offers a haunting parallel to its final occupants’ fate. It depicts Phrixus and his sister Helle from Greek mythology—fleeing on a golden-fleeced ram from their cruel stepmother. In the scene, Helle is shown reaching desperately toward her brother just before she falls into the sea, giving her name to the Hellespont.

Though likely decorative and devoid of religious significance to the home's residents, the fresco now mirrors the very real desperation experienced within those same walls.

“The fresco becomes a chilling echo of what took place,” Zuchtriegel noted. “The image of Helle clinging to Phrixus is reflected in the final moments of those who sought safety in this house—clinging to each other and to the hope of survival.”

A Pattern of Hope—and Tragedy

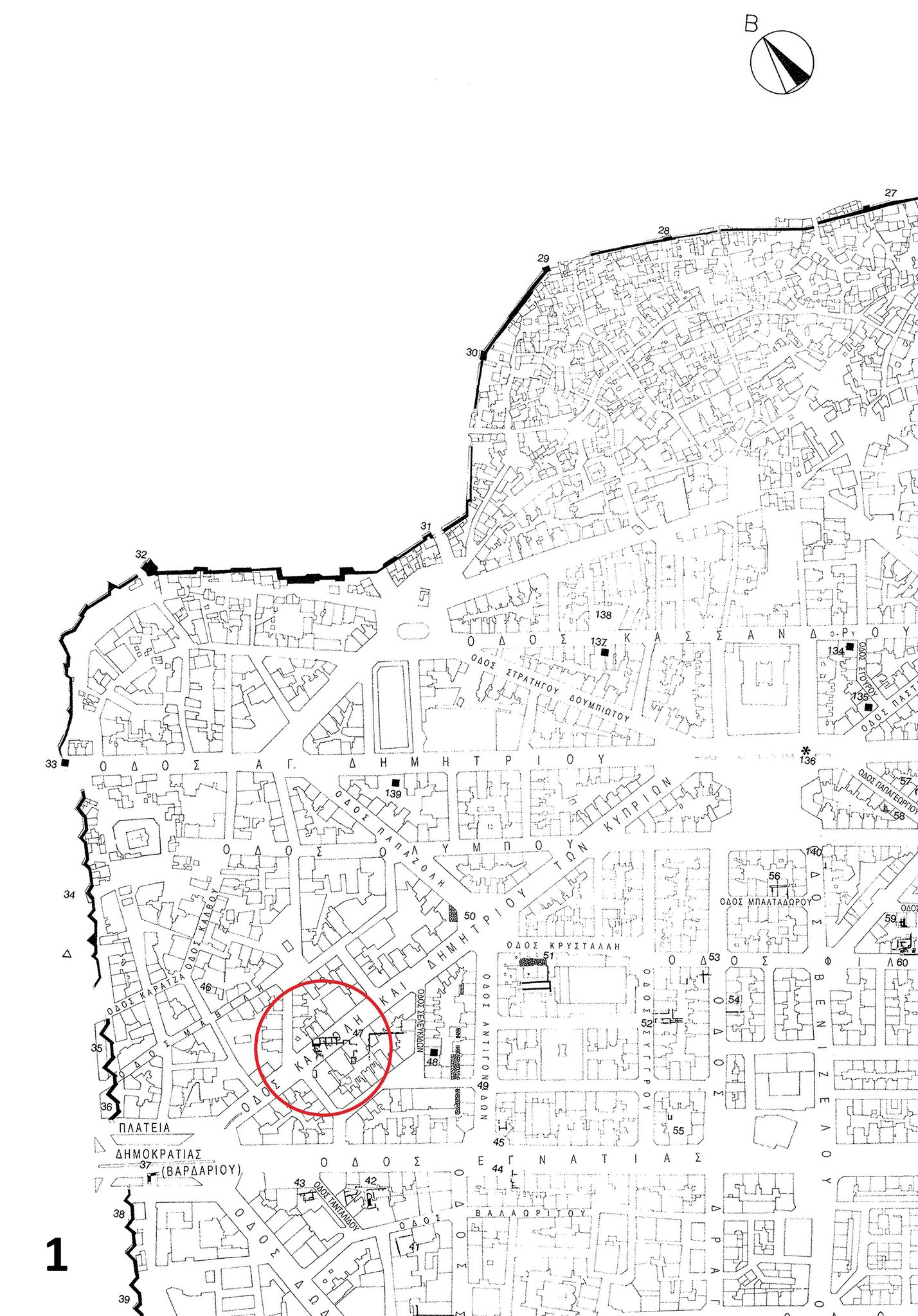

This discovery is one of many that highlights the varied ways Pompeii’s residents responded to disaster. In another house, two individuals had secured themselves in a narrow hallway, blocking both ends in a futile attempt at safety. Elsewhere, a young man and an older woman sealed themselves into a small room—only to be trapped when volcanic debris piled up outside, cutting off escape.

“Many people sought safety in enclosed rooms, likely believing they offered greater protection than open courtyards,” said Zuchtriegel.

Preserving Human Stories Through Science

To better understand the lives of Pompeii’s final residents, archaeologists created a plaster cast of the bed used in the barricade. By identifying the hollow left behind after the original material decomposed, they could capture its shape in detail—an eerie yet powerful tribute to the lives that ended there.

“Excavating Pompeii always brings surprises,” Zuchtriegel said. “Each discovery uncovers not just fragments of objects, but fragments of human stories—stories of fear, loss, and the enduring hope of survival.”

Final Thoughts

The story of Pompeii continues to unfold, not just as a tale of cataclysm, but as an extraordinary window into the resilience and humanity of those who lived there. With each excavation, archaeologists piece together narratives that are both profoundly personal and universally moving—a timeless reminder of how closely life and death, beauty and tragedy, have always walked hand in hand.