Paleontologists have determined that a skeleton discovered during a landscaping project belonged to a horse from the Pleistocene Era.

The horse had arthritis when it died. It is possible, too, that it had bone cancer in one ankle.

That can happen to any horse once it gets to be a certain age. This one is nearly 16,000 years old.

In 2018 paleontologists identified the skeleton of a horse from the ice age in Lehi, Utah — a particularly unusual discovery given that much of the western part of the state was underwater until about 14,000 years ago. Buried for thousands of years beneath seven feet of sandy clay, the remains were discovered only when the Hill family began moving dirt around their backyard to build a retaining wall and plant some grass.

Laura Hill said she and her husband, Bridger, uncovered the skeleton on September 2017, but didn’t think much of it at first. They wondered if it was a cow; Lehi is about 15 miles from Provo and was once mostly farmland that hugged the edges of nearby Utah Lake. She consulted a neighbor, a geology professor at Brigham Young University, who examined the bones, and guessed they were from a horse from the Pleistocene Era.

“I was shocked,” Ms. Hill said. “This is something we did not expect.”

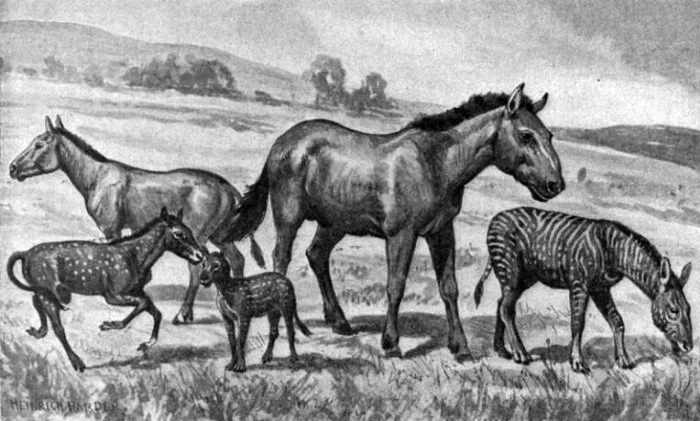

Utah is home to several fossil sites where dinosaurs and other ice age animals, including mammoths, mastodons and saber-toothed tigers, have been discovered. Horses have roamed North America for 50 million years, said Ross MacPhee, a curator in the department of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History. During the Pleistocene Era, the continent was dominated by two kinds of horses, he said, adding that he believes today’s domesticated horses are linked to one of those breeds. Despite harsh conditions, Mr. MacPhee said, “those horses could live anywhere.”

Rick Hunter, a paleontologist at the Museum of Ancient Life, a short drive from the Hill home, said Ms. Hill approached him last month to investigate the family’s discovery.

“She came in and said, “I found a skeleton in the backyard and I don’t know what to do,’” Mr. Hunter recalled. “I replied, ‘I do.’” Last week he and a team from the museum’s lab, where they study dinosaur fossils, went to her home.

The skeleton was missing its head, but was otherwise intact. Mr. Hunter estimated the horse to be the size of a Shetland pony; it was found lying on its left side, with all four legs tucked near its torso. Parts of the skeleton were damaged from exposure to weather. Curious onlookers had picked at the ribs and other bones.

Mr. Hunter did not know how the animal died, but he has a theory. Utah was covered during the last ice age by Lake Bonneville, a prehistoric lake. (The Great Salt Lake as it currently exists is a remnant of Lake Bonneville.)

Perhaps the horse was trying to escape from a predator and ran into the lake, Mr. Hunter surmised. “Horses can swim,” he said. “Maybe it got trapped out there, drowned and sank to the bottom.”

Mr. Hunter said he and his team visited the site at the Hill home for two days last week to excavate the remains. The bones were uncovered in a sandbank seven feet below the surface. “This is not uncommon,” the paleontologist said. Still, there was the question of what happened to the head.

He broadened the search to 50 feet beyond the original site. In the expanded area the group found bone fragments, molars and small pieces of the skull. Mystery solved: The skull had been shattered and moved when the landscaper cleared the land.

The skeleton was taken back to the museum, where it was cataloged, preserved and repaired. Unlike with dinosaurs, the horse’s bones were dehydrated and not yet fossils. Fossilized minerals in bone turn to stone, but the horse was not old enough for that to have happened. That posed a problem for Mr. Hunter’s team. “If they dry too quickly, they will crack,” he said. “You have to cure them slowly.”

Mr. Hunter also hopes to pin down the horse’s age with greater precision. The current estimate of 14,000 to 16,000 years is the team’s best guess until it can be studied further. Once the skeleton is reassembled, Mr. Hunter said, he would like it to become a permanent exhibit at the Museum of Ancient Life. Mr. MacPhee of the American Museum of Natural History concurred.

“It’s important that it ends up in an institution somewhere,” he said.

Ms. Hill said she and her husband were not sure what they were going to do yet. She said neighbors had flocked to the backyard to see the oddity before it was removed, and family members were advising the couple to have the skeleton appraised. (They are hoping to get a tax deduction if they donate it.) “It would be nice to have it here at the museum,” Ms. Hill said. “Mr. Hunter does want us to donate it.”

When Mr. Hunter visited last week he brought a volunteer who talked to the neighborhood children about Lake Bonneville, ancient animals and, of course, the horse in the backyard. Mr. Hunter said he would name it “Hill Horse” in honor of the family that found it.

Ms. Hill was pleased. “Now all these little kids want to be paleontologists,” she said with a laugh.