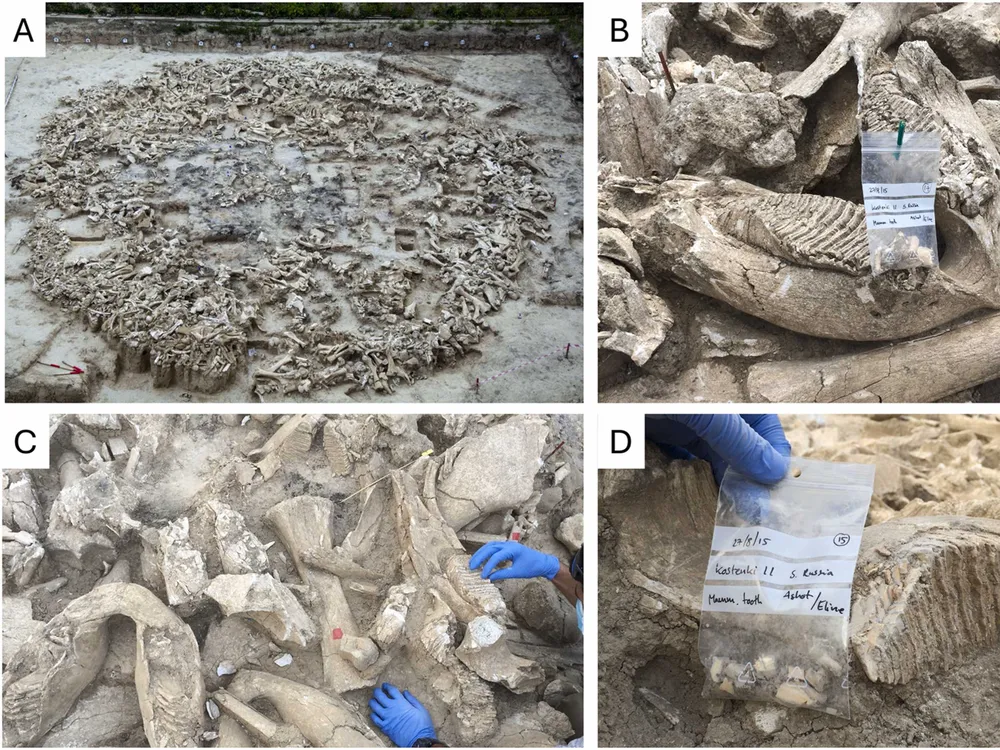

Archaeologists continue to unravel the mysteries of a massive, 25,000-year-old circular structure made from mammoth bones, discovered at the Kostenki 11 site in Russia. This impressive construction, spanning 40 feet in diameter, was built using the remains of over 60 woolly mammoths. While the purpose of the structure remains uncertain, recent DNA and radiocarbon dating analyses are shedding new light on how Ice Age hunter-gatherers sourced the bones and utilized the site.

A Remarkable Ice Age Discovery

Kostenki 11, located about 300 miles south of Moscow, is one of approximately 70 known mammoth-bone structures found throughout Eastern Europe. The site has been under excavation since its discovery in 1951, revealing multiple bone structures over the years. However, in 2014, archaeologists made the most significant find yet—a massive circular construction composed of nearly 3,000 mammoth bones from at least 64 individual animals.

Alongside the bones, researchers uncovered charred wood, burned mammoth remains, and remnants of plants resembling modern potatoes, carrots, and parsnips. Additionally, three large pits were found nearby, adding to the mystery of how the site was used.

Was It a Shelter, a Storage Site, or a Ritual Space?

The structure’s size and design have puzzled researchers for years. While it may have served as a shelter, its vast dimensions suggest it was unlikely to have been completely roofed. Another theory proposes that Ice Age hunter-gatherers used it as a butchering site, storing mammoth meat in nearby permafrost to preserve it. Some experts believe the site could have held ceremonial or ritualistic significance.

What DNA and Radiocarbon Dating Reveal

To gain a better understanding of the mammoths used in the structure, researchers analyzed 39 bone samples using DNA sequencing and radiocarbon dating. Their findings provided several key insights:

Most Mammoths Were Female: Of the 30 mammoths analyzed, 17 were female and 13 were male. This suggests that hunter-gatherers were likely scavenging bones from herds rather than trapping lone male mammoths. In woolly mammoth social structures, females and juveniles typically lived in herds, while adult males tended to roam alone. If the hunter-gatherers had been using traps, a higher proportion of males would likely have been present.

Mammoths Came from Different Herds: DNA evidence showed that the mammoths were not closely related, indicating that they originated from multiple herds rather than a single population.

Bones of Different Ages: Radiocarbon dating revealed that some bones were several hundred years older than others. This suggests that Ice Age humans may have scavenged remains from natural bone beds that contained both recently deceased and long-dead mammoths. Alternatively, the site may have been used in two distinct periods, separated by centuries.

Piecing Together the Past

While many questions remain unanswered, these findings provide valuable insights into the survival strategies of Ice Age hunter-gatherers. The ability to utilize available materials—whether from freshly hunted animals or scavenged remains—demonstrates their adaptability to the harsh glacial environment.

“This site gives us a glimpse into how our ancestors endured extreme climate conditions during the last Ice Age,” explains archaeologist Alexander Pryor from the University of Exeter. “It’s a remarkable story of resilience and survival.”

As research continues, Kostenki 11 remains one of the most intriguing archaeological sites from the Ice Age, offering a deeper understanding of how early humans thrived in a challenging and unforgiving world.