Because human subsistence depended on the timing of planting, flooding, or game reproduction, the seasons have always been significant to humanity.

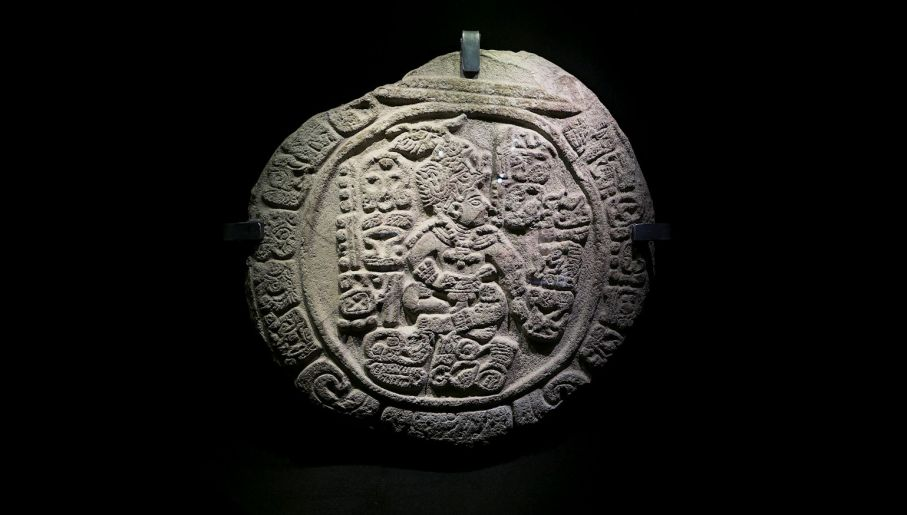

K'awiil Yopaat of Quiriguá, symbol of the twentieth day -- Ahau (Ajaw). Late Classic period (653AD), a reference to the Maya calendar and their god K'awiil. Photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana. Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia

The calendar, however, is more than just the language of life; it is also its poetry, the enchantment through which we attempt to exert control over reality and time.

That is why people began creating and erecting specifically orientated structures thousands of years ago; these constructions can now only be seen from a bird's eye perspective.

Also, people were inventing their own time frames that were shorter than our 365-day calendar year.

Eternity is coming, and time is running out. According to the sundial painted on the wall of Wadowice's parish church of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, it bears this slogan. The town, which is close to Kraków, is a long way from Mesoamerica, the region where the oldest pre-Columbian 260-day calendar was recently sensationally discovered. The quotation was obviously significant even for cultures that were so apart by time and distance.

Every culture makes an effort to represent time measurement in some way. It can be tiny at times, like a sundial, or it can be epically large, like the 260-day calendar that was made along the Gulf of Mexico coast. A "pocket" version was more recently uncovered in Guatemala as a fresco on a pyramid wall.

The findings demonstrate that even without the cold certainty of a scientific background, individuals could measure time at that time.

Our earthly environment is characterized by chaos and disorder, but the sky's is by uniformity, rhythmicity, and harmony. Thanks to the observation of the skies, which has been a preoccupation of mankind from the dawn of time, it became possible to harness reality through the measurement of time itself, including times of day and of the yearly seasons.

A public debate has been sparked by French research on non-pictographic signs found in Paleolithic caves in Europe that were decorated like cathedrals by our ancestors anywhere between 12 and 30 thousand years ago. The oldest lunar calendar created by Homo sapiens, according to scientists, is 20–30 thousand years old. This indicates that the astronomical observations of the starry sky that allowed for the creation of such a calendar were made by individuals who had only learned how to properly smooth a stone, without the use of magnifying glasses (since there were none).

When discussing Mesoamerican calendars with Dr. Stanisaw Iwaniszewski of Warsaw's State Archaeological Museum and Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, I am reminded that as much was suggested more than 50 years ago by Alexander Marshack, who studied the linear incisions on bone objects from those distant centuries.

"The oldest discovery is thought to be a bone fragment from Abri Blanchard, which dates to around 31 000 BC and is from the Aurignacian civilisation. Marshack claims that this results from a computation based on observing the moon phases. Each mark on the bones' surface would represent a day (or night), and they would nearly match the Moon's form (waxing, full, or waning). Marshack discovered 69 characters, or a span of two months and ten days. The works of Boris Frolov on Paleolithic calendar records and mathematics were well-known in the 1970s "the archaeologist claims.