DNA from a 2,500-year-old Sicilian battlefield shows that mercenary troops were not just widespread but also the ideal of Homer.

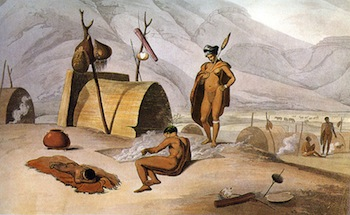

A mass grave of troops from the second Battle of Himera in Sicily in 409 B.C. One-fourth of the combatants are thought to have been mercenaries, compared to two-thirds in the first Battle of Himera seven decades earlier.

There will always be mercenaries—hired soldiers whose only shared trait may be a desire for adventure—wherever there is an out-of-the-way conflict. Some people enlist in foreign armies or rebel groups because they support the cause, while others do so because the deal is too good to pass up.

This was true in ancient Greece, despite what ancient Greek historians would have you believe. According to them, the polis, or independent Greek city-state, stood for the triumph of citizen equality and civic pride over kingly despotism. In their accounts of the first Battle of Himera, a bloody conflict in 480 B.C. in which the Greeks from several Sicilian cities banded together to repel a Carthaginian invasion, neither Herodotus nor Diodorus Siculus mentioned mercenaries. Mercenaries were viewed as the opposite of the heroic Homeric figure.

According to Laurie Reitsema, an anthropologist at the University of Georgia, "being a wage earner had some negative connotations — avarice, corruption, shifting allegiance, the downfall of civilized society." This makes it understandable why ancient scribes would accentuate the Greeks against. Greeks component of the fights rather than acknowledge the price they had to pay.

However, research reveals that the soldiers defending Himera were not as exclusively Greek as historical chronicles of the time would have it. This information was published in 2022 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Many people saw the triumph to be a turning point in Greek identity. However, a recent study that examined the degraded DNA from 54 bodies discovered in Himera's freshly discovered west necropolis discovered that the majority of the tombs were occupied by professional troops from distant locations such those now known as Ukraine, Latvia, and Bulgaria.

The discovery supports research from 2021 in which Katherine Reinberger, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Georgia, and her colleagues conducted a chemical analysis of the tooth enamel of 62 deceased warriors buried close to Himera's ancient battlefield, the scene of two significant battles: one in 480 B.C., when Himeran forces defeated the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Mago, and a second battle seven decades later, when Hamilcar's grandson returned for vengeance According to Dr. Reinberger's team, locals made up around one-third of the fighters in the initial conflict but three-fourths of them in the subsequent fighting. Principal author for both papers is Dr. Reitsema.

The new analysis, according to Greek historian Angelos Chaniotis at Princeton's Institute for Advanced analysis, sheds new information on the makeup of the fights at Himera, if not on how they turned out. "It confirms the general picture that we had from ancient sources, while at the same time highlighting the role of mercenaries," he said. Although they frequently hide in plain sight, mercenaries are mentioned in our documentation.

The ruins of the Temple of Victory, built after the first Battle of Himera in 480 B.C. and razed after the city’s capture in 409 B.C.

Their paper "suggests that Greeks minimized a role for mercenaries, possibly because they wanted to project an image of their homelands being defended by heroic Greek armies of citizens and the armored spearmen known as hoplites," according to David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard whose lab generated the data. Armed forces made up of commandos hired for a fee would presumably invalidate this theory.

Tyrants who dominated Greek Sicilian cities during the Hellenic Age enlisted soldiers of fortune for territorial expansion and, in certain cases, as bodyguards because they were so despised by their subjects. Dr. Reitsema claimed that the hiring of mercenaries even led to the usage of currency in Sicily to pay them.