In the heart of the Sahara Desert, in what is now southwestern Libya, there once existed a thriving civilization known as the Garamantes. These remarkable people built cities and towns in an environment that is now considered one of the harshest and most arid on Earth. Their story, dating back 2,400 years, sheds light on the remarkable human capacity for adaptation and ingenuity in the face of challenging conditions. Yet, it also serves as a stark warning about the unsustainable use of natural resources, a lesson we must heed in our modern world.

The Sahara of today is a vast and unforgiving desert, characterized by scorching temperatures and a severe scarcity of water. But it wasn't always this way. Over 5,000 years ago, the Sahara resembled a savanna similar to the modern Serengeti, replete with waterholes and abundant wildlife. This region, with its ancient pastoral landscape, is even considered one of the two places where pottery was invented. However, by the time the Garamantes established their society, the Sahara had transformed into the challenging desert we know today.

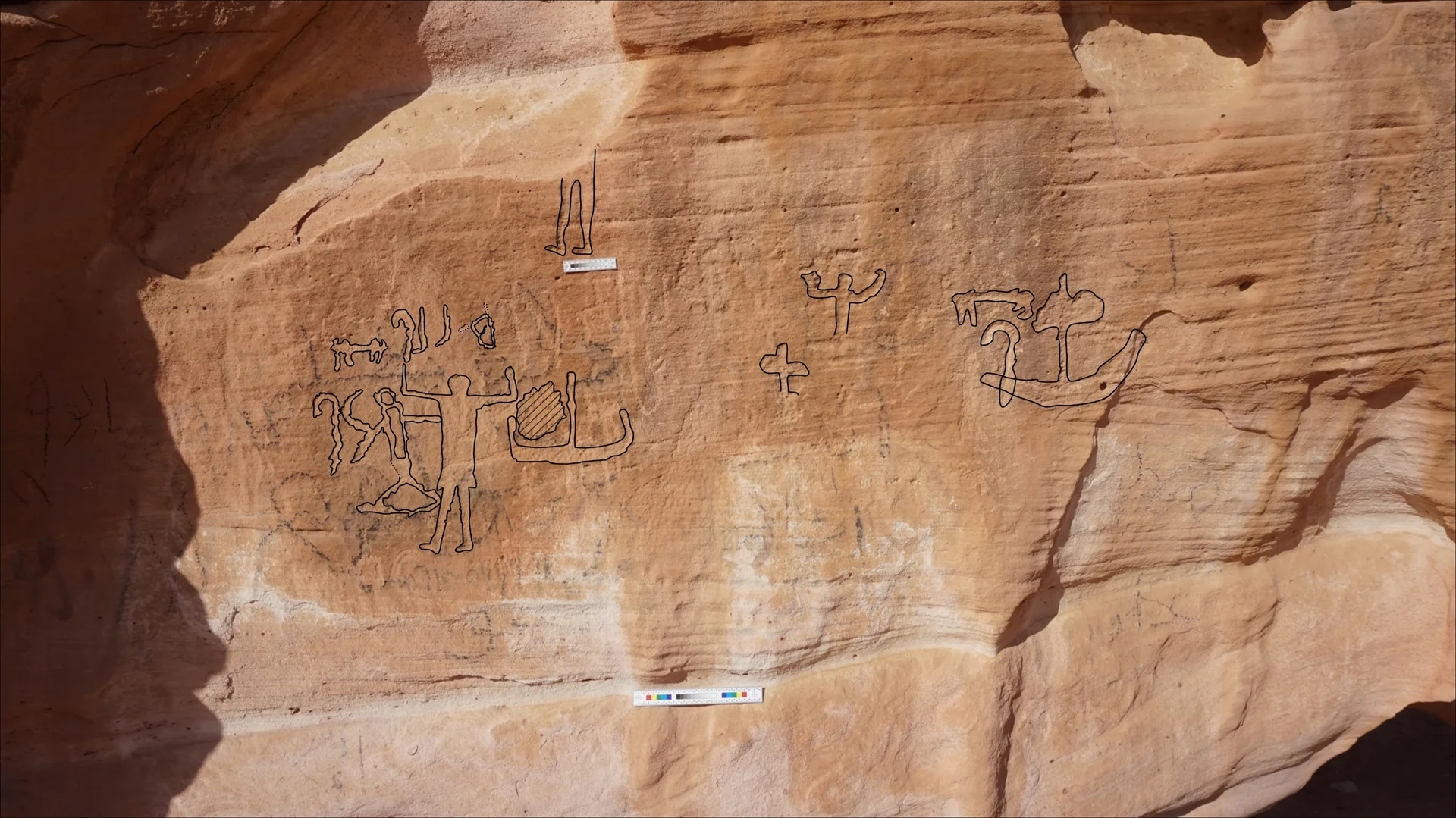

What makes the Garamantes' story so extraordinary is their ability to tap into a hidden natural resource that would sustain their civilization for centuries - groundwater. The key to their survival lay in a clever irrigation technique that involved the construction of angled tunnels, known as qanats or foggara in the Berber language, into water-rich hillsides. These tunnels allowed them to access groundwater and channel it to irrigate the arid valleys below.

The Garamantes' genius was to find the one place in the Sahara where the groundwater sat high enough above the valley floor to be tapped

Image Credit: NASA/Luca Pietranera

This ancient technique was not unique to the Garamantes, as other civilizations in dry regions had employed similar methods. Professor Frank Schwartz of Ohio State University suggests that the Garamantes may have borrowed the idea from Persia, where such irrigation systems had been in use for over a thousand years.

While the Garamantes were referenced by writers of their era, much of the historical accounts were plagued by inaccuracies. Some even erroneously attributed their accomplishments to the Romans. It was not until the 1960s that archaeology began to correct these misunderstandings. Still, the question remained - why did the Garamantes have access to such a vast and sustainable source of groundwater?

Professor Schwartz has shed light on this puzzle. He has shown that the sandstone aquifer beneath this part of the Sahara is one of the largest in the world when full. Although the Sahara had experienced periods of being a fertile grassland with rainy seasons, it had been millions of years since it had been genuinely wet. During this wetter period, water from a vast catchment area flowed to the base of the Messak Settafet massif, providing a consistent water source for the Garamantes over centuries.

For the Garamantes, Wadi el-Agial must have appeared as a paradise. With an ample water supply and a buffer of vast deserts separating them from potential invaders, they likely enjoyed a higher standard of living than any other civilization in the Sahara. Their success is a testament to human resourcefulness and adaptability in the face of extreme environmental challenges.

Water flows downhill, even when it is underground, but if the floor of a valley sits below the top of the groundwater in the hills it can be available without pumping

Image Courtesy: Frank Schwartz

However, as with many stories throughout history, the inevitable outcome was driven by human behavior and our tendency to exploit resources until they are depleted. The Garamantes constructed an impressive network of tunnels, stretching over 450 miles, to access the aquifer. The longest of these tunnels extended for over 2.7 miles. As the region became increasingly arid and the groundwater recharge ceased, their once-abundant water source began to dwindle.

Professor Schwartz notes that "the qanats shouldn't have actually worked" because they relied on annual water recharge, a process that no longer occurred. The groundwater eventually dropped below the level of the tunnels, and around 1,600 years ago, the Garamante civilization was abandoned.

The fate of the Garamantes serves as a warning for our own time. As we look at modern examples like the San Joaquin Valley in California, we see that people are depleting groundwater at a faster rate than it can be replenished. While our methods of water extraction may differ from the Garamantes, the underlying issue remains the same - we are draining our precious groundwater reserves at unsustainable rates.

California's recent history of droughts, followed by a wetter year, illustrates the precarious balance we face. If the trend of drier years continues, we may find ourselves in a situation similar to that of the Garamantes. Replacing depleted groundwater supplies can be expensive and ultimately impractical. We must learn from the Garamantes and take steps to manage our natural resources wisely, ensuring their sustainability for future generations. The ancient Sahara civilization's story is a powerful reminder that we must cherish and protect the gifts the Earth provides, rather than squandering them in pursuit of short-term gains.