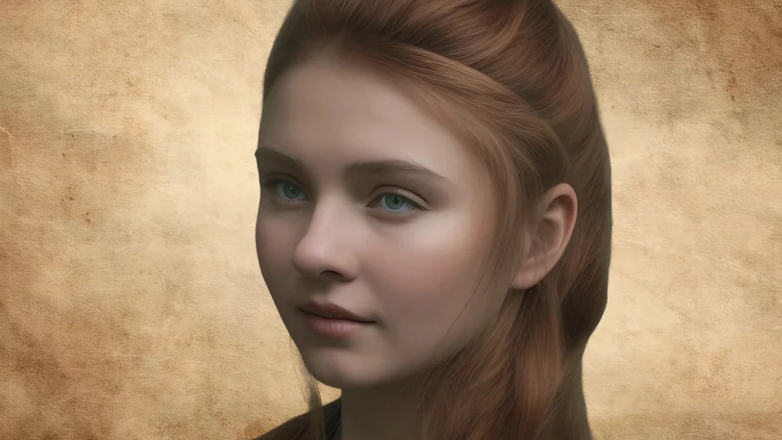

Thanks to cutting-edge facial reconstruction technology, a woman who lived in Greece more than 3,500 years ago has been digitally brought back to life. Her face, once buried in a Mycenaean royal cemetery, has now been reconstructed in striking detail—and the result is both haunting and unexpectedly modern.

As reported by The Guardian, the digital reconstruction is based on a facial mold dating back to the 16th century BCE, from a burial site discovered in the legendary city of Mycenae—once the stronghold of King Agamemnon. The woman was around 30 years old at the time of her burial in what is believed to have been a royal tomb. The site was first uncovered in the 1950s.

Dr. Emily Hauser, the historian who commissioned the digital reconstruction, described the result as “breathtaking.” Speaking to The Observer, she remarked, “It took my breath away. For the first time, we can see the face of a woman from a kingdom tied to figures like Helen of Troy and Clytemnestra—she could be imagined as their sister.”

The reconstruction was created using a clay mold crafted in the 1980s by researchers from the University of Manchester, and brought to life through digital artistry by Juanjo Ortega G.

Dr. Hauser—whose upcoming book “Mythica: A New History of Homer’s World, Through the Women Written Out of It” publishes next week—highlighted how advancements in forensic anthropology, DNA analysis, carbon dating, and 3D printing have transformed our ability to reimagine the ancient world. “For the first time, we can truly look the past in the eye,” she said.

A Burial Rich with Clues

What makes the discovery even more significant is what was found alongside the woman’s remains. Among the grave goods were a gold-electrum mask and three swords—initially believed to belong to a man buried beside her, thought to be her husband. But recent DNA analysis revealed that the two individuals were not spouses, but siblings. And the swords? They were likely hers.

“The traditional assumption is that when a woman is buried next to a man, she must be his wife,” Hauser explained. “But DNA confirmed they were brother and sister. This woman was in that royal tomb because of who she was—not who she married.”

Her presence in such a prestigious burial, combined with the weapons found by her side, signals a radical shift in how historians view women’s roles in the Late Bronze Age. New data shows that in some tombs from this period, “warrior kits” appear more frequently beside women than men, prompting scholars to rethink long-held assumptions about gender and warfare in the ancient world.

A Glimpse Into Her Life

Analysis of her skeleton also revealed signs of arthritis in her spine and hands—likely from years of intensive textile work. “It’s a reminder of the physical toll on women at the time,” Hauser noted, referencing Helen in The Iliad, who is famously described as weaving.

This extraordinary reconstruction does more than reveal a face—it reshapes our understanding of an entire era. Through science and storytelling, the ancient world is speaking once again, and the voice we hear now is, for once, a woman’s.