The Decipherment of Cuneiform: A Journey Through History

The decipherment of cuneiform, one of the oldest writing systems in the world, has involved the tireless efforts of numerous academics and the use of ground-breaking methodologies. This article delves into the intriguing story of how cuneiform script, used in ancient Persia, was finally decoded, revealing the rich history and insights hidden within these ancient inscriptions.

Early Knowledge and Curiosity

The journey towards deciphering cuneiform began with the inquisitiveness of travelers who explored the ruins of Persepolis in Iran. They were drawn to the enigmatic Cuneiform inscriptions that adorned the ancient structures. Even though some attempts at decipherment were made in the medieval Islamic world, these early endeavors proved largely unsuccessful.

In the 17th century, travelers like García de Silva Figueroa and Pietro Della Valle made significant observations about the cuneiform inscriptions at Persepolis. They noted the direction of writing, from left to right, and realized that these inscriptions represented words and syllables rather than mere decorative friezes. Englishman Sir Thomas Herbert even correctly guessed that these symbols were words and syllables to be read from left to right.

The first cuneiform inscriptions published in modern times were copies of the Achaemenid royal inscriptions in Persepolis, with Carsten Niebuhr publishing the first complete and accurate copy in 1778. These copies played a crucial role in the later decipherment efforts.

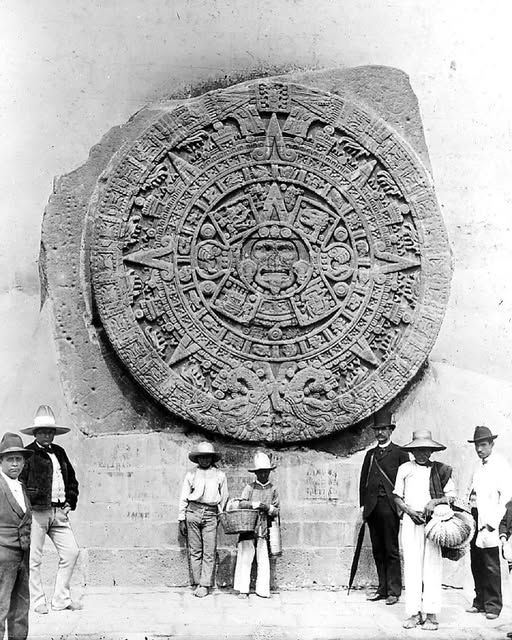

Old Persian alphabet, and proposed transcription of the Xerxes inscription, according to Georg Friedrich Grotefend. Initially published in 1815. Grotefend only identified correctly eight letters among the thirty signs he had collated.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend's Breakthrough

The actual decipherment of cuneiform began in the early 19th century, when Georg Friedrich Grotefend initiated the study of Old Persian cuneiform. Grotefend's groundbreaking work, though initially met with skepticism, led to the realization that certain inscriptions contained the names of kings and their titles.

Carsten Niebuhr was a traveler who brought back inscriptions from Persepolis to Europe in 1767, and these inscriptions would later be known as Old Persian cuneiform. Niebuhr realized that these inscriptions had a simpler set of characters, which he called "Class I," and he believed it to be an alphabetic script with only 42 characters.

Around the same time, Anquetil-Duperron returned from India with knowledge of Pahlavi and Persian languages, and he published a translation of the Zend Avesta in 1771, which introduced Avestan, an ancient Iranian language. This provided the foundation for Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy to study Middle Persian in 1792–93 during the French Revolution.

In 1793, de Sacy published his findings about the inscriptions at Naqsh-e Rostam, which had a standardized structure mentioning the king's name and titles.

Oluf Gerhard Tychsen studied the inscriptions from Persepolis in 1798 and found that the characters indicated individual words by oblique wedges. He also noticed a recurring group of seven letters and some common terminations.

Friedrich Münter, the Bishop of Copenhagen, built upon Tychsen's work and suggested that the inscriptions belonged to the time of Cyrus and his successors, likely in the Old Persian language. He identified a recurring sequence as "King" and correctly deciphered it as "King of Kings," with its Old Persian pronunciation as xšāyaθiya.

This Old Persian cuneiform sign sequence, because of its numerous occurrences in inscriptions, was correctly guessed by Münter as being the word for "King". This word is now known to be pronounced xšāyaθiya in Old Persian (𐎧𐏁𐎠𐎹𐎰𐎡𐎹), and indeed means "King".

These efforts by early scholars laid the foundation for the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform and the understanding of ancient Persian history.

A pivotal moment in the decipherment occurred in 1823 when French philologist Champollion, who had deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, confirmed the accuracy of Grotefend's identifications by reading an Egyptian dedication to King Xerxes I in a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription.

In 1836, French scholar Eugène Burnouf identified and published an alphabet of thirty letters used in cuneiform inscriptions. This discovery marked a significant step in understanding the Cuneiform script.

Decipherment of Elamite, Akkadian, Sumerian, and Babylonian

Henry Rawlinson's visit to the Behistun Inscriptions in 1835 was crucial as they contained identical texts in three official languages: Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite. Rawlinson successfully deciphered Old Persian cuneiform and laid the foundation for deciphering the other scripts present in the Behistun Inscriptions.

The decipherment of Old Persian paved the way for deciphering Akkadian, a close predecessor of Babylonian. The techniques used to decipher Akkadian remain somewhat mysterious, but the work of Henry Rawlinson, Edward Hincks, Julius Oppert, and William Henry Fox Talbot played essential roles in deciphering Akkadian and eventually Sumerian.

The decipherment of cuneiform script is a testament to human curiosity, perseverance, and collaboration across centuries. From the first observations by early travelers to the groundbreaking work of scholars like Grotefend, Burnouf, Rawlinson, and Hincks, the journey of deciphering cuneiform has unlocked the ancient history of Persia and provided insights into the rich tapestry of human civilization. Today, modern technology continues to aid in the study of cuneiform, preserving this invaluable piece of our past for generations to come.