Directions in Democracy: Interview with Prof. Paul Cartledge. Richard Marranca for The Archaeologist

Q1. Can you define the word “democracy”? Where did it begin (and end) and how far did it spread?

A. Etymologically, the ancient Greek coinage dêmokratia (first attested c. 425 BC/E) combined dêmos and kratos. The meaning of kratos is unambiguous: power or might. The meaning of dêmos, however, is ambiguous: either ‘people’ (the people as a whole, the city or state, e.g., Athens) or the majority of the empowered (adult male citizen) people, a.k.a. the masses or (if you didn’t like them) the mob or rabble. So, ancient Greek dêmokratia could mean either ‘the power of the people’ (as in Lincoln’s ‘government of the people by the people for the people’) or the power of the masses (over both the organs of state governance and over the elite few citizens). If you were a member of the elite Few rich citizens, you might well prefer oligarchy (rule of the elite Few) to democracy, which you might see as merely mobocracy or mob-rule (further below, Q5).

Origins and spread: Some scholars have sought to identify ‘democratic’ or ‘proto-democratic’ institutions in other times and places and cultures (see further below, towards the end of this interview), but if what is taken to matter most is the power of decision-making and, as part of that, the power to call executive office-holders to account by judicial or other means, then the first democracy properly so called anywhere in the world was that of Athens, brought into being in stages during the approximately half-century between c. 508/7 and 462/1 BC/E. There were some 1000 separate political entities in Hellas (the Greek world) between about 500 and 300 BC/E; of those, perhaps a quarter, perhaps as many as half at one time or another within those two centuries experienced some form of democracy (Aristotle in his Politics treatise of c. 330 identified four main types); but pioneering Athens (which experienced three or four forms over time) was the most consistently and extensively democratic of all.

The Roman conquest of Greece in the last two centuries BC/E put an end to all forms of ancient Greek (direct) democracy. The recuperation and revival of (indirect, representative) democracy began in the 17th century in England, spread from there to the United States and France in the 18th, and more widely in the world from the end of the 19th. Full adult (women as well as men) suffrage democracy was an achievement of the 20th century. The ‘largest’ existent democracy (since 1947) is India. But all modern democracies (especially those that are democracies merely in name, e.g., the People’s Democracy of China) are representative, not direct: it is representatives (however selected, whether nominated or elected) who actually govern and rule on a day-to-day basis, not ‘the people’ (however defined) as such.

Q2. According to your brilliant, wide-ranging study, Democracy: a Life (O.U.P., NY & Oxford, new edition 2018), there are solid reasons for the invention of democracy. Can you situate us back then to show what inventions and trends in Greece, and specifically in Athenian society, led to democracy?

A. This is an exceptionally tough ask! Preconditions of what I take to be the origins of democracy at Athens (see below on Solon v. Cleisthenes) include: invention c. 700 BC/E of the polis (city-state, citizen-state), a rule-bound political entity based on a definition of the privileges and duties of citizens (always free adult males); weakening of the original rule over poleis by exclusive aristocracies (literally ‘the power of the best’, in fact of the richest and most noble families) through such factors as intermarriage between noble and non-noble families, the impoverishment of some aristocrats, and the rise of new-wealthy families due to for example success in overseas trade; the shift from long-range fighting conducted only by the most wealthy to the dominant role of infantry phalanx fighting undertaken by more middling-rich heavy-armed soldiers; and the emergence in some of the larger, more important poleis(Athens was one) of sole-ruler autocrats called ‘tyrants’ who found it helpful to dispossess or weaken the older ruling families by spreading political power more widely down to poorer, commoner citizens.

Q3. What about Greek religion, oracles and such? How was that part of the conversation on democracy? And how about science and democracy?

A. Religion, oracles, etc. Religion was never seen as a distinct sphere, separate from a secular sphere, so democratic politics was always heavily invested in and inflected by religion. Yet the Greeks had no single word for ‘religion’, but used periphrases such as ‘the things of the gods’, ‘gods’ being understood as a plural, polytheistic term embracing both gods and goddesses. The overriding goal of human relations with the divine pantheon was to keep the most relevant gods and goddesses happy, to maintain the ‘peace’ of the gods, by duly ‘acknowledging’ them through animal blood-sacrifices, prayers, festivals, etc. The democratic Athenians between them devoted more days of the year to festivals of the various divinities than did any other Greek city. All such Athenian festivals, whether national or local, were managed democratically. Likewise, all matters of religion, including oracles,. There were many Greek oracular shrines scattered throughout the Greek world (in Asia and Africa as well as Europe), but the most famous was that of Apollo at Delphi in central mainland Greece. Consultations here, both personal and state, began in the 8th century BC/E. One of the most famous episodes of the Athenian official state consultation of the Delphic Oracle occurred under the democracy in the 480s BC/E in anxious preparation to face a massive impending invasion by the empire of Persia. The Delphic priestess gave conflicting responses to different consultations, so it fell to the Assembly of the Athenians to decide which interpretation to favour and act upon. Happily, they chose correctly, built a large fleet of trireme warships, and Athens emerged victorious from the Persian Wars—and with its still-evolving democracy intact.

Science: Around 600 BCE, there emerged a tendency for a very small elite group of Greek intellectuals on both sides of the Aegean Sea to question the inherited religious worldview in favour of a more scientific, mechanistic understanding of the cosmos, how it came into being, and what it was composed of. But it took a very long time before the role of gods and goddesses in making and determining the nature of the world was seriously challenged by any large number of citizens. The earliest thoroughgoing Greek atheists are not attested until towards the end of the 5th century BC/E, well after the introduction of democratic systems of government.

Q4. In order to understand Athenian democracy, is Solon or Cleisthenes a good starting point? Who are the major Democrats? And what were the major institutions of democracy?

A. Solon or Cleisthenes? Greeks liked the idea of ‘founding fathers’, people they called ‘legislators’ or ‘lawgivers’ and to whom they sometimes actually paid religious worship as ‘heroes’ after their deaths. The earliest of them belonged to what we call the 7th century BC/E, but some of them (e.g., Lycurgus of Sparta) were more mythical than historical. The Athenians had two rival ‘Founders’ of their democracy: the more conservative citizens looked back to Solon (c. 600 BC/E), the more radical to Cleisthenes (c. 500 BC/E). Both men belonged by wealth, family, and upbringing to the elite few, but both, like Pericles most famously later on (c. 450 BC/E), believed in giving power to the ‘People’. The question is: what kind of power, how much, and to which people? Most scholars now agree that Cleisthenes was the true founder of classical Athenian democracy. The reforms that went under his name in 508/7 included a redefinition of citizenship itself, a recalibration of relations between the central organs of governance and the local constituencies, the invention of a new council to serve as the standing committee for the Assembly, and a reorganisation of the regionally recruited and arrayed hoplite land army. Further reforms were introduced in a package proposed by Ephialtes with the support of Pericles in 462/1. But Ephialtes was murdered shortly after, in a contract killing, and rather unfairly, his name was never added to the list of ‘legislator’ founders.

Major Democrats: very few surviving writers were ideological Democrats (see further below), and none of the leading democratic politicians of Athens apart from Demosthenes (below) has left us any written works on the theme. The four most prolific extant authors on classical Greek democracy—the Athenian aristocrat Plato (c. 428–347) and his most famous pupil, originally northern Greek Aristotle (384–322), son of a royal physician; and the Athenian pamphleteers Isocrates (436-338) and Xenophon (c. 428–354)—were all non-democrats, though of these, Plato was by far the most hostile to democracy, which he saw as the rule of the ignorant, fickle, unenlightened majority over the educated, intelligent minority. Outside Athens, several tens of other Greek cities were at one time or another more or less democratic, e.g., Thebes in the 4th century BC/E, but, as at Athens, no leading democratic statesman (e.g., Epaminondas of Thebes) has left us any writings. Apart from Pericles (below) and Demosthenes, the leading Athenian democrats of different stripes included: Cleisthenes (c. 570–500), retrospectively credited as the founder of Athenian democracy as such, though he was by birth an aristocrat with a foreign (Sicyonian) mother; Cleon (??–422), the principal successor to Pericles as the most influential war politician of the 420s; and Aeschines (389–314), who lost out to Demosthenes on the major issue of resistance to the rise of the (non- and anti-democratic) kingdom of Macedon.

Institutions.

Local: At base were the 139 or 140 Attic (Athenian) demes: in order to be an active, empowered (free adult male) citizen, one had to be officially enrolled at the age of 18 on the register of the deme of one’s (citizen) father. One’s father or nearest relative swore that the 18-year-old was who he said he was and who his father was, and that his parents had been legally married when they produced him. Demes held assembly meetings, celebrated festivals, and managed military call-ups.

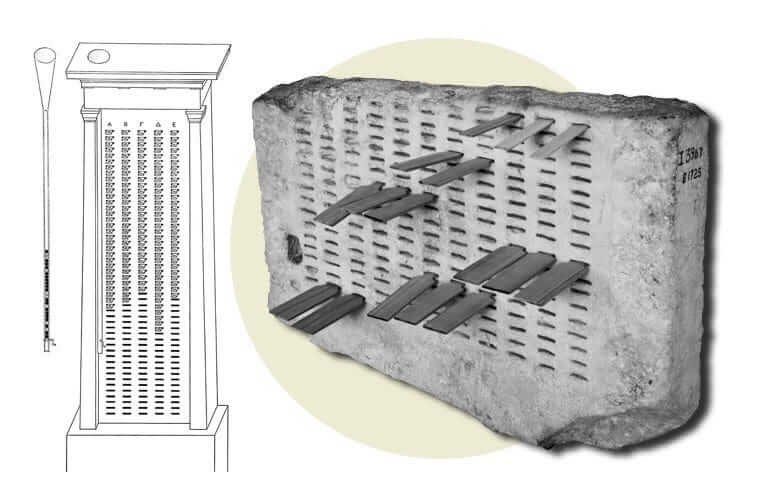

National/Central: The ultimate decision-making body was the ‘demos of the Athenians’, meeting regularly (at first once a month, eventually four times every 35 or 36 days) in Assembly to decide on matters put to them by a steering committee known as the Council (Boulê), a body of 500 citizens aged over 30 chosen by lot on a deme-quota basis, which was in almost permanent session throughout the civil year. Councillors counted as ‘officials’, of which there were altogether some 700 domestic and (during the last seven decades of the 5th century) a further 700 holding office abroad in what we call an Athenian ‘empire’ (though it wasn’t anything like the Persian, Roman, or British). Most officials were, like the 500 Councillors, selected by lot; only the top three executive offices, the Generals, Treasurers of Athena (Athens’s patron deity), and (in the 5th century only) the ‘Treasurers of the Greeks’, and one or two other officials (e.g., in the 4th century, the Water Commissioner), were chosen by election—partially because of the need for expertise and partly so that, if they failed or committed crimes in office, they could be brought to account through heavy fining—or worse (up to and including execution). Generals and Treasurers served on boards of 10, and almost all boards were appointed and reappointed annually. Elections were considered undemocratic or anti-democratic since they favoured notabilities, whereas the random lot encouraged, recognized, and favoured the essential contributions of ordinary citizens.

Q5. What about Greeks who didn’t like democracy? Did they see it as a precarious mob rule?

A. They did. They coined a special word, ochlokratia, meaning the power of the ochlos, or mob. An elite writer such as the historian Thucydides spoke scornfully of the ‘naval mob’, meaning that most of the Athenian citizen sailors who rowed the warfleets that were the basis of Athenian external power in the 5th century were drawn from the lower socioeconomic orders, the masses. Some fanatical Greek ultra-oligarchs, as reported by Aristotle (who was himself a moderate oligarch), even took a religious oath that they would do as much damage and harm as they possibly could to the hated poor masses of citizens! By that, they meant not only keeping them out of power by monopolising offices themselves and by making and enforcing other anti-democratic laws, but also using their monopoly power to exploit the masses economically through rack rent or other forms of debt.

Q6. You write about how Athens and its allies promoted democracy and how other powers (Sparta, Philip, Alexander, and Rome) didn’t. Were there common methods used to crush democracy?

A. It’s difficult to generalize. One of Thucydides’s major themes is stasis: civil strife (usually economic, often ideological) or outright civil war. He takes as his paradigmatic instance the outbreak on the island of Corfu (in ancient Greek, Kerkura) in 427 BC/E, in which the Athenians militarily supported the democrats and the Spartans the oligarchs. It was paradigmatic because, he says, from 427 on, stasis broke out ever more frequently throughout the Greek world, and the two great powers of the day, Athens and Sparta—who were also at the time warring enemies—would use their interventions on behalf of democrats and oligarchs in different cities as a technique of both imperial expansion and military engagement. The two typical demands of Democrats in oligarchically run cities give a clue as to the nature of the economic basis of stasis: ‘cancel debts’ (often agricultural loans or town rents) and’redistribute the land’. Most Greek cities and states were fundamentally agrarian, and the source of most oligarchs’ wealth, apart from trade, was agricultural landownership and surpluses of staple crops (cereals, olives, and wine grapes—produced for them by slaves or tenants). Oligarchs reinforced their economic superiority by making moral-cultural claims, saying that only they were the ‘good’ or ‘best’ citizens, whereas the poor Democrats were the ‘bad’ or ‘worst’.

Q7. Along with the political champions of democracy, who were the historians and authors who were on the side of democracy?

A. There were very, very few such champions! Of the historians, I’d single out Herodotus (c. 484–425), who, arguably, was a moderate democrat. When trying to explain the democratic Athenians’ unexpected victory over the Persians at the battle of Marathon in 490 BC/E, he put it down to their fundamental notion of citizen equality. (The other core concept of democracy was freedom—both freedom from and freedom to.) But even Herodotus reported scornfully that the Athenian democracy could make stupid collective decisions. Among other kinds of authors, the most prominent democrat on record is Demosthenes (384–322), super-wealthy like Pericles. His democratic views were expressed in the published versions of speeches he had delivered without a text in the Athenian Assembly meetings (held on the Pnyx hill), usually on matters of foreign policy, so that he would often contrast the (superior) Athenian democrats and democracy with their non-democratic Spartan opponents. But that didn’t stop him from also blaming the citizens of the Athenian democracy, either for being more interested in hearing speeches than taking appropriate action or (in the case of the richer citizens) failing to pay their taxes.

Q8. Was Aristotle for a mixed constitution and governing system? Is that the same kind of path as modern democracies? Is this similar to the balance of powers idea in the modern world?

A. Yes, Aristotle was for a mixed constitutional and governmental system, which he saw as a compromise between giving exclusive or preponderant power to either the rich Few or the poor Many citizens. It is and it isn’t similar to our ‘balance of powers’ notion. Similar, because it includes the idea of checks and balances between the two salient groups. Not similar, because our notion of a balance of powers depends on the prior notion of a separation of the powers of government: legislative, executive, and judicial. ancient Greeks did not hold that notion; they believed that political power-holders should exercise power in all three spheres alike, even to the point of acting in one sphere (judicial) to revise or counteract a decision they themselves had taken in another (legislative). An ancient Greek polity was seen as a strong community—strong but therefore all the more worth fighting for control over! Hence stasis; see above.

Q9. It was great the way you explained Pericles and the (5th-century) Golden Age (as well as Alexander the Great) on BBC’s In Our Time and in your books. Can you tell us about Pericles, his famous speeches, and his great role as a leader and promoter of democracy? Who advised him? What were his failings?

A. That’s a huge question, big enough for a whole book—there have been several life-and-times modern biographies of Pericles (c. 492-429), and I’m contemplating writing another soon! Our main surviving source is a life written by the famous Boeotian biographer Plutarch (c. 100 CE), and he had available to him many written texts that have since been lost. But he wasn’t a historian (he was mainly interested in moral character), and he didn’t know what to do with what seemed a contradiction to him, living as he did in a non- or anti-democratic age under the Roman Empire. The contradiction was that Pericles seemed to him to be, on the one hand, a true statesman who rose above sordid personal and ideological politics to act impartially for the good of the Athenians as a whole, but yet, on the other hand, just another political operator keen to achieve and maintain personal power by any means possible!

The answer to the apparent contradiction is that Pericles was probably quite a lot of both. The chief piece of evidence for his views on democracy as a governmental system and way of life is a speech that historian Thucydides wrote, based no doubt on what Pericles had actually said in a civic funeral oration in 431/0, but expressed according to Thucydides’ memory and in Thucydides’s own style of Athenian Greek. Since Thucydides was not himself a democrat (he was a somewhat moderate oligarch), it is thought that that explains why Pericles’ views expressed here are less than radically egalitarian and democratic. Pericles had a small coterie of intellectual advisers with whom he discussed and initiated policy. He regularly spoke persuasively in the Assembly before audiences of upwards of 5000 or 6,000 in the open air. But he was also a tireless backroom technocrat, particularly good at public finance, including helping to manage the public, religio-political (re)building programme on the Acropolis that produced the Parthenon temple. His one big failing was to overestimate the reserves and other resources Athens had at its disposal in 431 in order to resist the onslaught from Sparta and to underestimate the effect on morale that his strategy of mostly passive resistance would have on his people. He couldn't, of course, be blamed for failing to predict the Great Plague of Athens (from which he himself died, as did his two sons), but his policy and strategy did make the funereal effects of it much worse.

Q10. Did the Roman Republic (or other ancient societies) have any inkling of democracy? How about tribal or pre-political cultures? Do tribes have informal practices that can be identified as democratic?

It’s vital to distinguish between the supremely political Roman Republic and cultures that may be labelled ‘tribal’ but are certainly in key respects pre-political. This is a distinction that those who wish to assign the term ’democracy’ even to such pre-political societies, notably in Asia and Africa, fail to observe. For example, ‘primitive’ democracies have been identified in 3rd millennium BC/E Assyria or ‘traditional’ (pre-colonial) India, but in all such cases, not only is politics properly so-called absent, but the most that is permitted to ordinary ‘people’ (not of course citizens) below the (usually hereditary) tribal chief or dynastic monarch is some form or degree of ‘discussion’, but nothing approaching collective, popular decision-making power.

The Roman Republic is a special case—and a special problem—from the point of view of democracy. Its very name means, literally, the ‘popular thing’ or the ‘thing of the people’, and formally speaking, absolutely every public political decision, whether taken by vote in one other legislative or electoral assembly or in a ‘People’s’ lawcourt, was a decision of the Roman people. However, here we would do well to remember Lincoln at Gettysburg, quoted above: was the government of the U.S. ‘people’ in 1863 really, in any useful sense, democratic? The great historian Polybius, a conservative, oligarchic Greek of the 2nd century BC/E who was so much an admirer of the Roman governmental system that he attributed to it the source of Rome’s external power and empire, something of which he approved, thought that he could see a strong democratic element or elements in the Roman system, but even he categorised it overall not as a democracy but as a’mixed constitution’, the democratic elements being counterbalanced and outweighed by the oligarchic and the monarchic or residually regal. We, however, might better take our cue from another historian of Rome, the great Tacitus (c. 55–120 CE), who wrote that’mixed’ constitutions existed only in speculative theory and not in hard, material practice. For in reality, the Roman Republic was a traditional, aristocratically inflected oligarchy of wealth, in which there were no one-man, one-vote legislative, policymaking, or electoral assemblies, but state policy was determined by a handful of senior elected executives within the aristocratic-oligarchic Senate, literally a body of ‘Elders’ but actually composed of nobles and notables aged over 30, and delivered by a small body of all-powerful, non-responsible’magistrates’.

Q11. Was democracy too quixotic or odd for societies—from Imperial Rome to the 1600s or so—to bother with it? Was the subject too hot to handle?

A. Not, I think, too quixotic (though both Republican and Imperial Rome produced relatively few speculative, utopian political thinkers, as opposed to Cicero, the classic prophet-of-things-as-they-are, steady-state, reactionary oligarchic thinker), but, yes, too hot. Rome as an imperial power, first in Italy then throughout the Mediterranean and beyond, always followed the lead of Sparta, systematically favouring, to the extent of radically intervening militarily to impose, oligarchies of conservative, propertied aristocrats or semi-aristocrats among their subordinate ‘allies’. Imperial Rome from Augustus (27 BC/E-14 CE) on was of course an autocracy or dictatorship, no matter how hard at least the earliest Emperors tried to disguise it as a (restored) republic. For the nature of the Republic as a political system, see immediately above.

Q12. I recall a lot in your book about the Magna Carta, Machiavelli, Cromwell, Hobbes, Rousseau, Tocqueville, and more. Can you comment on some of the important aspects and people?

A. The reasons for which the object and persons you mention are included in my book vary greatly! Broadly speaking, Machiavelli, Rousseau, and Tocqueville may be invoked as democratic or proto-democratic, whereas Cromwell and Hobbes belong firmly to the anti-democratic tradition. In more detail, the Florentine Machiavelli (1469–1527), author of The Prince, was heir to a medieval Italian tradition of city-republics in which a political place was reserved for some construction of il popolo (‘the People’), but the very title of his most famous work tells us that in practice, the most he could have been hoping to achieve was moderate autocracy or dictatorship inflected in a vaguely populist direction. J-J Rousseau (1712–1778), a Swiss-French philosopher and educator, first formulated the notion of the ‘general will’, a far more democratic notion than, say, Cicero’s ‘will of the populus’. He was considered, together with Voltaire, one of the two greatest intellectual influences on the French Revolution (which had a democratic element). Alexis, count of Tocqueville (1805–1859), was the author of a brilliant, officially commissioned study that he entitled Démocratie en Amérique (1839–40). The word ‘democracy’ in its French form had been borrowed into anglophone discourse; Tocqueville repaid the compliment by emphasising the egalitarian, democratic spirit of (settler, colonial) Americans a score of years before Lincoln became the first US President to be elected, in 1860, on an explicitly anti-slaveowning ticket.

Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) was, of course, by definition, a small republican, since he led the movement of regicide that executed King Charles I in 1649. But as Lord Protector under the shortlived English Republic (1649–1660), he showed definite authoritarian, undemocratic, and even regal tendencies. Three authors of the Republican period exemplify the fierce ideological debates that caused and were caused by the act of regicide: the poet John Milton (1608-1674) and the political theorist James Harrington (1611-1677) were both for the Republic and showed proto-democratic leanings, whereas Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), a political philosopher, was all for the re-establishment of an all-controlling sole rule and blamed the ancient Greeks (some of them!) for being all too peskily democratic.

Magna Carta (1215 CE, sworn between King John of England and a select group of Barons) is ambiguous: a couple of its clauses, most famously the one prescribing habeas corpus, can be seen as folding without friction into more genuinely democratic regimes such as that (‘constitutional monarchy’) established by the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688/9, but in origin and intent there is nothing democratic whatsoever about Magna Carta as such.

Q13. There is little direct democracy in Western countries, though there are many representative democracies and republics. Can you explain that?

A. The issue is tripartite: size, ideology, and technology. In the ancient Greek world, which was endowed with communications technology at a distance, democracy had to be direct. But that technological necessity was reinforced by ideology: it was believed that the people as such ought to or had to govern, both as themselves and for themselves, for a set purpose. And the combination of low technology with a belief in the virtue of direct rule was further reinforced by the very small size of ancient citizen bodies, the modal size of which is estimated to be between 500 and 2000 adult males. The ancient Athenian democratic citizen body, normally around 30,000 but sometimes increasing up to 50 or 60,000 and sometimes decreasing to 20,000 or below, was altogether exceptional, off the scale. But a normal figure for the attendance at a regular Athenian democratic assembly meeting on the Pnyx hill is thought to have been a more manageable 5 or 6,000, with 6,000 being set as the minimum required, the quorum, for valid voting on certain issues, such as the award of citizenship to a non-Athenian foreigner. Whoever/however many turned up at an Assembly meeting or at an electoral meeting were officially deemed to be ‘the people’ for legal-constitutional purposes. Likewise, any ‘People’s’ jury, selected by lot from a panel of 6,000, whether 201 or 2,501; a usual figure (as at the trial of Socrates) was 501, the large size aimed at preventing effective bribery. The Athenians were therefore perfectly able to incorporate the idea of representation into their fundamentally and definitionally direct system of democracy.

Direct democracy within the basically representative systems of contemporary (Western) democracy is understandably very rare, given all the fundamental ways—size, technology, and ideology—in which contemporary democracies differ from those of ancient Greece. There is, however, one mode of democratic political action that, as used in some modern democracies and in some (e.g., Switzerland) much more frequently than others, approximates more nearly the ancient Greeks’ direct ways of reaching political decisions, and that is the use of the plebiscite or referendum. Significantly, both of those terms have a Latin, not a Greek, etymology, since far more contemporary European and Euro-American civil and criminal law is derived from Roman than from ancient Greek law. Different democratic countries have different rules for how, on what issues, or in what form a referendum may be couched, held, and evaluated in the overall process of governance. Radical Democrats today argue that direct democracy—or elements of direct democracy—should be enhanced, for example, by incorporating it into the very lawmaking process itself. But few if any argue that a modern democracy, one in possession of nuclear weapons of mass destruction, for instance, should take advantage of the latest digital communications technology to introduce direct self-government by referendum on a daily basis.

Q14: Is there an inherent contradiction? Like this: cities and civilization created democracy. But this produces extremely powerful individuals and groups—hierarchies. What do you think?

A. Only indirectly did cities and civilization (the latter derived etymologically from the former) produce/create democracy. It is true, however, that democracy was/is a culture, a way of life, not just a system of governmental organization and popular decision-making. For instance, humans in ‘nature’ aren’t all equal, so to make equality a fundamental core democratic value is to act culturally, not naturally. Institutions, of course, take time to establish and have to be forged and tested to destruction. Humans are social beings, but they require conscious acculturation to dominant shared values. Democracy is not the work of a day. On hierarchy, see answers to Q15 and 18.

Q15. Most, if not all, organizations have one leader or an oligarchy. Would that be the case for corporations and universities too, and so on?

A. In the early 20th century, German sociologist Robert Michels promulgated his ‘Iron Law’ of oligarchy, to the effect that, no matter how democratic any large organization—or society!—might intend and proclaim itself to be, actually in time it would in practice be run oligarchically, that is, by a small group of people effectively beyond the reach and control of the ‘ordinary’ members of the organization (whether a business corporation or a university). Specialists in the history of the ancient Athenian democracy have argued vigorously—and I believe successfully—against applying any such ‘iron law’ to Athenian politics between about 500 and 320 BC/E, but they are happy to claim (and again, I agree with them) that the ‘Law’ does apply to the Roman Republic. As for modern organizations and societies, I’d say that a weak version of Michels’s Law—a lead rather than iron law, perhaps—does generally apply universally, though in some cases (Xi Jin Ping’s China, e.g.) more obviously than in others.

Q16: Is direct democracy slow and inefficient for organizations? Is it also the case that the rich and powerful (or anyone) just prefer a steady state or enlargement of their position?

Q17. One thing I’ve noticed is that powerful people on the Left make all sorts of lovely ideal announcements, but that much of it doesn’t stand for themselves but for society or “the masses” out there. Like celebrities with their private jets. Or in the USA, people who tout the equality of public schools or busing their kids to more diverse schools or affirmative action—but don’t have that for their kids, of course.

A. I think those two questions/observations can usefully be answered together. It all depends on what you mean by ‘efficiency’, and whether you’re thinking only in terms of values that can be measured quantitatively or/and of issues that can and should be evaluated qualitatively. Aristotle was surely right to give an essentially economic, class-based analysis of how power was distributed and exercised in the Greek political communities and societies he knew. I would add that that analysis can also usefully be applied universally, mutatis mutandis. On the side of values, the Funeral Speech attributed by Thucydides to Pericles (see above) contains one remarkable passage on shirkers, or what we call free riders. Such people, who fail to make their proper civic contribution to the common good, have, Pericles says, no place in democratic Athens. Again, I would suggest that that argument doesn’t apply only to an ancient democracy.

Q18. Our cousins on the evolutionary scale are prone to having alpha males; chimpanzee colonies have male leaders that rule over everyone and rule by might.Is the hierarchical nature of things (as a researcher such as Jane Goodall might say) just built into human &comparable non-human animal social life?

Sociobiologists (such as the late E.O. Wilson) and ethologists would say yes, certain tendencies—such as the aggressive struggle for alpha status—are hardwired into, say, chimpanzee colonies and, insofar as humans are evolutionarily the direct descendants of such primates, into human ‘colonies’ (polities, societies) too. Against which I, as a historian, would urge the claims of ‘culture’ or ‘nurture’ as being comparable or even superior to those of ‘nature’, from two main points of view, one ancient, one modern. From the ancient point of view, I would call in evidence again Herodotus and his pioneering histories. Running like a red thread throughout is the interpretive notion that humans, when organized politically, make strikingly different political choices, often overdetermined by considerations such as religion or warmaking. Some go for imperial autocracy (the Persians), others for democracy (some Greeks). Yet evolutionarily speaking, they were all much the same as human social beings. Likewise in modernity: in 1934, brilliant US social anthropologist and ethnographer Ruth Benedict published her Patterns of Culture, in which she examined closely three ‘cultures’ widely scattered in space and therefore unable to interact with or upon each other. Her point was: My, how different! All three were human cultures, but their underlying norms and beliefs and their attitudes and social practices were so utterly different from each other.

Q19. You mentioned digital democracy on p. 310. What are the five major qualities of democracy?

A. I’m not sure that ‘digital’ is what I would have thought of first when thinking about democracy’s major qualities, partly because digital technology is an enabling and not intrinsically a determining factor, and partly because some of the consequences of the digital revolution have been, in my view, dire for my understanding of what democracy is or could best be. Ironically, ancient Athenian democracy was also digital: votes in assembly were taken by raising the right hand, and in the lawcourts, jurors scratched on wax tablets—a longer line for the heavier penalty, a shorter line for the lighter penalty.

Five major qualities (which all have to be interpreted, cashed out, and finessed): equality (especially of respect, and of opportunity); freedom (from slavery or other external force, and freedom to participate); what’s been known – since Aristotle – as the ‘wisdom of crowds’ (some people are smarter, more committed, more persuasive etc etc than others, but – throw as many persons’ opinions as possible into the mix and the resulting compromise agreement is likely to be as good or a better decision than one achieved by just one or a few persons); democracy of necessity uniquely fosters the four cardinal virtues both individually and more especially collectively (prudence, justice, courage/fortitude, and temperance/self-control); finally, negatively, as Prime Minister Churchill memorably put it, democracy is the least worst system of governance out of all those that have so far been tried!

Q20. Lately with students I’ve been discussing literature / culture from the 1920s, Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, Hemingway stories, the Harlem Renaissance… We were talking about how our era shares a lot of scary stuff from the 1920s -- the rise of fascism and nationalism,militarism, economic problems, and more? Lenin started the idea of the one-party vanguard state, and although he considered that to be a form of democracy, it was anything but liberal. The governments of China and Russia and others today hate any form of, and especially liberal Western-style, democracy. How fragile are our Western democracies? Is this authoritarian or fascist streak gaining ground around the world?

A. Very fragile, and yes, they are increasingly under threat globally, both externally and sadly, internally, from authoritarian or neofascist regimes. If I may, I would like to bring the debate much closer to home—that is, your home in the USA and mine in the UK. Was (ex-President) Donald Trump behind the January 6, 2021, insurrection and assault on the Capitol?The jury is still officially out, but the evidence is increasingly conclusive that he was. Likewise, there is surely little doubt that his other legal attempts to reverse the actual popular vote of November 2020 were similarly motivated, namely by a fierce desire not to surrender the exceptional powers entrusted to a US President in office and, above all, not to make himself vulnerable to due legal retribution for any crimes or misdemeanours he may have committed in or when seeking office. On my side of the pond, if on a far smaller scale, ex-Prime Minister Boris Johnson (trained as a classicalist) was the first PM in UK history to have been found guilty of a criminal offence and fined for it. But it is rather his reckless desire to ride roughshod over longstanding parliamentary conventions as well as over formal legal constitutional rules that concerned and still concerns me most as a Democrat. In both those individual cases, the norms, rules, and laws of democracy as currently framed seem to have triumphed. But for the future...

Q21. What about the misnamed countries with democracy in the title but which are totalitarian states? Or the democracies with antidemocratic qualities? It’s confusing out there! Can you comment on this?

A. The ‘People’s Democracies’ usually are or were not at all democratic: the People’s Republic of (Communist) China or the late and unlamented GDR (German Democratic Republic a.k.a. ‘East Germany’ – 1949–91) are classic cases. And those two are or were undemocratic for the same reason: ‘the People’ has been substituted politically by the (vanguard) Party, members of which are nominated and self-appointed and not responsible or accountable to the (real) People. To call the system ‘totalitarian’ is a rather more tricky issue conceptually, however, since the word implies that every political decision affecting individual and collective prosperity is taken centrally, hierarchically, and unidirectionally. Not even ‘absolute’ monarchs, however, actually wielded absolute power.

Q22. Overpopulation, climate change, the rise of technology, wealth inequality around the world, entertainment culture, and so on and so forth—what of those is a danger to democracy?

A. All of the above! But not only to democracy and democracies, of course. Climate change threatens us all alike with extinction. If by ‘entertainment culture’ is meant or included’social media’, then, alas, yes, the promised egalitarian and educational benefits of the online world have been overbalanced by fiercely regressive, antidemocratic exploitation.

Q23. What can each of us do to promote democracy, whether representative or direct?

A. Oscar Wilde, an Anglo-Irish writer, critic, and political activist (also classically educated), once observed that the trouble with socialism was that it took too many free evenings. Ditto democracy, or, at any rate, democratic activism. Since party politics seems to be here to stay for as long as representative democracy does, active membership in the local branch of a national political party is one obvious way to promote it. Another, purely modern way is to start and promote an online campaign, either as an individual or as hosted by an activist organization such as (in the UK) the New Citizenship Project. If by chance one’s campaign gains tens of thousands of supporters, even over 100,000, the UK government is obliged to hold an open debate on the topic, which might be a cultural-political issue such as the reunification back in Athens of all the Parthenon Marbles currently held outside (e.g., in the British Museum) or a definitionally political issue such as Brexit.

Q24. Do you have any favorite films, books, organizations, or people that promote direct democracy / democracy in general?

A. If I may interpret your question loosely: Aristophanes’s comedy Wasps (422 BC/E) is a brilliant satire on the workings of Athenian democratic justice, but its underlying message is that doing public-political community service as a juror was of the essence of being a democrat. If it’s the culture of modern democracy, its egalitarian spirit, that one is looking for, then US poet Walt (‘Leaves of Grass’) Whitman (1819–1892) and his Democratic Vistas (1871) are your men. Still, alas, of our own time and for our own time are George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949), which magnificently, terrifyingly, bear out Churchill’s ‘least worst’ dictum quoted above.

Q25. The future. It’s hard to see anything positive in most sci-fi literature and movies. Governments imagined there are often totalitarian and oligarchic. Do artists serve as radar—feeling and seeing something dreadful ahead? Are they warning us?

A. Apologies, but I must recuse myself here. My experience of sci-fi in any form is nugatory. But to use another analogy, independent, creative artists in all media may be likened to the topmost branches of a tree, which, in a storm, are the first to shake, bend, and even possibly break, giving advance notice of even greater change and either renewal or destruction to come down below.