Unraveling the Indo-European Enigma: The Indo-European puzzle may be explained by a hybrid of "farming" and "Steppe" hypotheses, yet also offers some differences from these earlier proposals.

MAIN POINTS OF THE NEW ANALYSIS:

Languages of the Indo-European family are spoken by almost half of the world’s population

Heggarty et al. present a database of 109 modern and 52 time-calibrated historical Indo-European languages

Analysis suggests the emergence of Indo-European languages around 8000 years before present

The findings lead to a “hybrid hypothesis” that reconciles current linguistic and ancient DNA evidence

Indo-European languages had an initial origin south of the Caucasus, followed by a branch northward into the Steppe region

Ancient DNA evidence brings valuable new perspectives but remains indirect interpretations of language prehistory

Language phylogenetics and ancient DNA suggest a hybrid hypothesis

The resolution to the Indo-European enigma lies in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses

A new database of Indo-European cognate relationships, called IE-CoR, is created.

IE-CoR covers 161 languages with a denser and more balanced sampling. The database provides more accurate date calibrations for nonmodern languages.

Lexical differences exist between major sublineages of the "same" language.

Divergence within Romance is accurately dated to the Roman Empire in the first centuries CE.

Divergence within Indic is dated to ~4370 yr B.P., in line with Vedic Sanskrit already being slightly divergent from the lineage(s) ancestral to modern spoken Indic languages.

The inference of an Indo-Iranic split at ~5520 yr B.P. may seem surprising, but it is consistent with the level of cognacy overlap between Early Vedic and Younger Avestan.

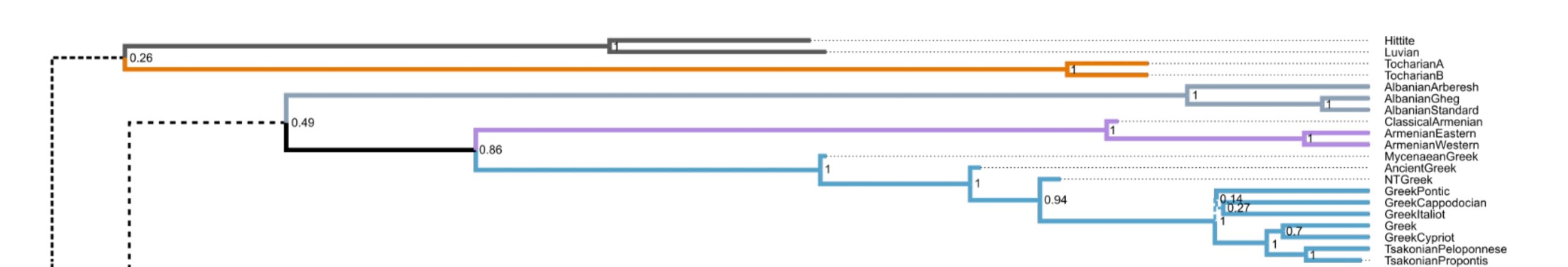

Greek goes with Armenian and Albanian, and a separate main European clade brings together Germanic, Celtic, and Italic. The Albanian, Greek, Armenian, and Anatolian branches separated much earlier than the others.

At the root of Indo-European, our results return Anatolian and Tocharian as deeply divergent clades with limited support for forming a joint clade.

The results contradict the idea that all branches of Indo-European originated on the steppe. Indo-Iranic branched off early, around 6980 years ago, contrary to the Steppe hypothesis. Steppe ancestry in South Asia cannot be reconciled with the earlier date for the separation of Indo-Iranic. Indic and Iranic had diverged from each other by ~5520 years ago.

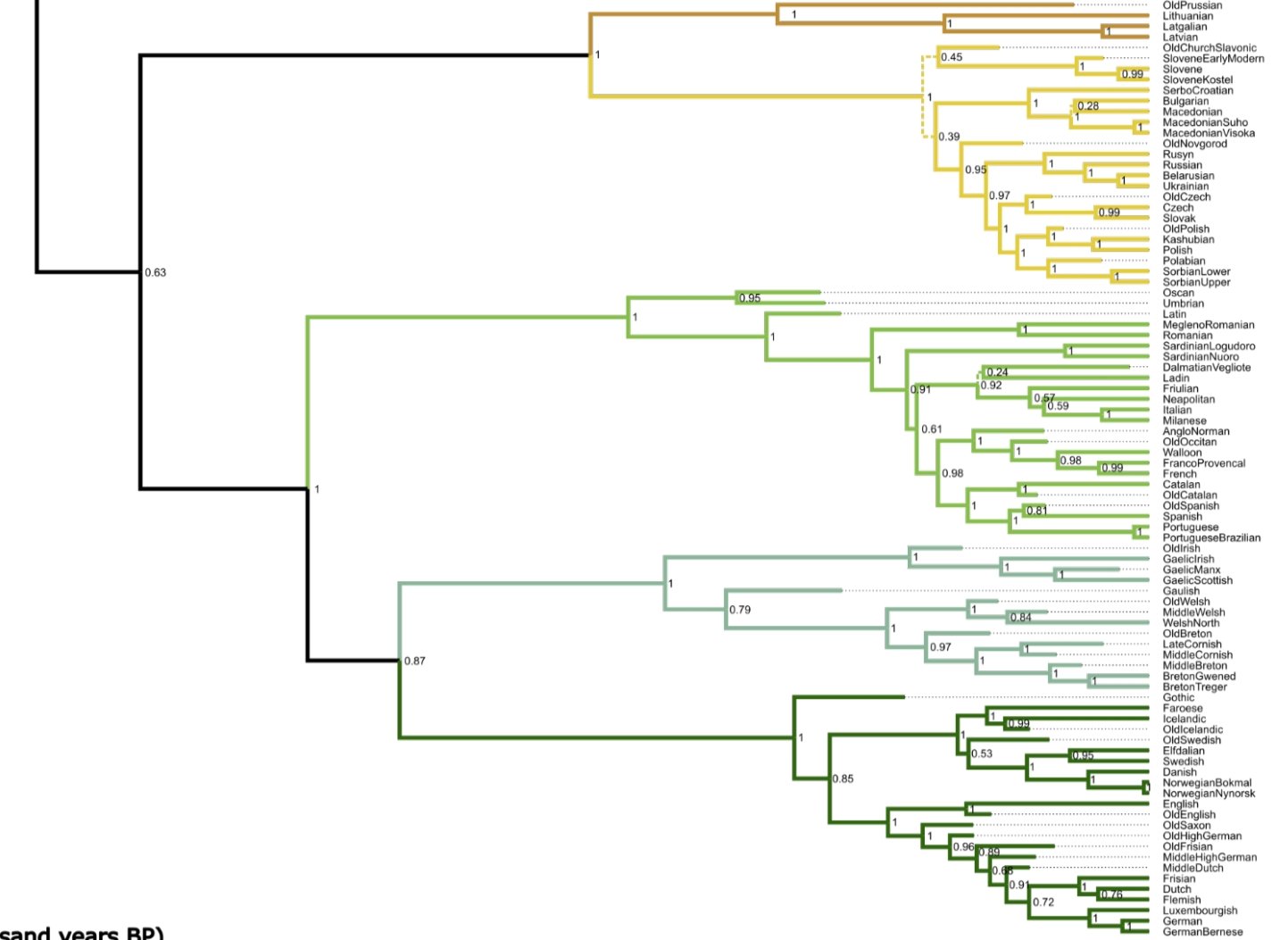

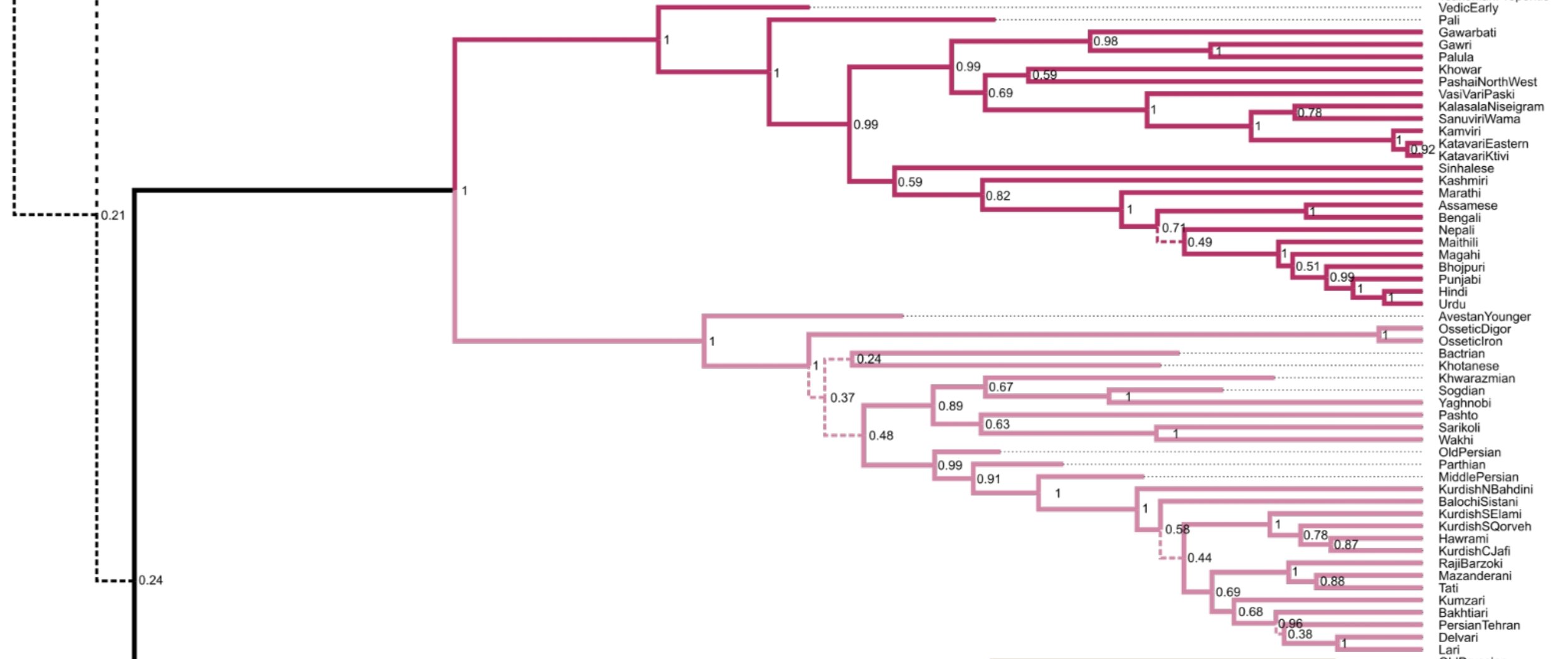

The posterior probability distribution of trees for the Indo-European family.

Distribution visualized using DensiTree (71). The time axis shows the estimated chronology of Indo-European expansion. Languages whose tips do not reach the right edge are the 52 nonmodern written languages such as Hittite, Tocharian, Mycenaean Greek, and Old English. These languages were used in the analysis as time calibrations. The two gray curves show the distribution of root date estimates for the tree. The prior is light gray, and the posterior estimate is dark gray. RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Indo-European languages, which include the vast majority of languages spoken in Europe as well as many spoken in Asia, have long been the subject of intensive research and debate. Their origins, dispersion patterns, and timeline of evolution are topics that have fascinated linguists and anthropologists for centuries. Recent evidence from a new analysis in Science Magazine suggests that the roots of these languages may go back as far as 8000 years before the present, considerably extending our understanding of their genesis.

The Indo-European language family, with over 400 languages, is the largest in the world. This family includes major world languages like English, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Greek, and Hindi, among others. Linguists have long tried to understand the origin of these languages, and the conventional wisdom is that they originated around 5000 to 6000 years ago. However, the latest analysis has proposed a significantly earlier date. Recent advances in linguistic and ancient DNA analysis are shedding new light on this complex puzzle, leading to what some researchers are calling a “hybrid hypothesis” that reconciles current linguistic and ancient DNA evidence.

This new revelation is the result of an international research collaboration that combined linguistic analysis with archaeology, anthropology, and genetics. The research involved an extensive study of ancient DNA samples and archaeological artifacts and a systematic comparison of linguistic patterns across different Indo-European languages.

By meticulously analyzing linguistic similarities and differences, researchers mapped out relationships between languages and constructed a tree-like model of language evolution. This allowed them to estimate a timeline for the development of various languages in the Indo-European family.

The study of ancient DNA samples and archaeological artifacts provided insights into the migrations of early humans. The researchers cross-referenced this data with linguistic evidence, allowing them to pinpoint the regions and approximate timelines for when different languages began to differentiate.

A DensiTree showing the probability distribution of tree topologies for the Indo-European language family.

The time axis shows the estimated chronology of the family’s geographical expansion and divergence, calibrated on 52 nonmodern written languages. Annotations add chronological context relative to selected archaeological cultures and expansions of significant ancestry components in the aDNA record. CHG, Caucasus hunter-gatherers; EHG, Eastern (European) hunter-gatherers; BMAC, Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Database of Indo-European Languages

In a groundbreaking effort, Heggarty et al. have presented a database encompassing 109 modern and 52 time-calibrated historical Indo-European languages. The meticulous analysis of this data suggests the emergence of Indo-European languages around 8000 years before the present (B.P.). This database, labeled IE-CoR, marks a significant upgrade over previous databases in terms of its comprehensive and balanced sample of languages and the accuracy of its date calibrations.

The implications of the lack of direct ancestry in languages, particularly those of the Indo-European family, can be deeply significant for our understanding of linguistic evolution. Contrary to common perceptions, lineage splits in phylogenetic analyses do not necessarily represent major differences between languages, indicating that languages can diversify and evolve independently while maintaining a common heritage. Furthermore, it is crucial to note that ancestry between historical, written languages and modern, spoken ones may not be fully direct. This suggests a complex interplay of linguistic influences and transformations over time that shape the way languages are spoken today. Additionally, the existence of lexical differences within major sublineages of the "same" language emphasizes the fluidity of linguistic evolution, illustrating how even seemingly similar languages can possess distinctive features and characteristics. Therefore, a deep understanding of these factors is paramount to fully grasping the complexities inherent in the study of Indo-European languages.

Linguistic Divergence and Splitting

The new process of linguistic divergence and splitting within the Indo-European language family represents a fascinating journey through history. For instance, divergence within the Romance languages is pinpointed with a high degree of accuracy to the era of the Roman Empire in the first centuries CE, reflecting the far-reaching influence of Roman civilization on language evolution. Meanwhile, divergence within the Indic languages can be traced back to approximately 4370 years before the present. This timeline aligns with evidence showing that Vedic Sanskrit, one of the oldest forms of Sanskrit, was already exhibiting a slight divergence from the ancestral lineages that would eventually evolve into the modern Indic languages. Perhaps more surprising is the hypothesized split of the Indo-Iranic languages around 5520 years before the present. While this may initially seem unexpected, it is indeed consistent with the degree of cognacy overlap found between Early Vedic and Younger Avestan, providing a unique insight into the intricate evolution of the Indo-European languages.

Indo-European languages through space and time.

(A) Indo-European languages covered in the IE-CoR database: 109 modern languages (round dots) and 52 nonmodern languages (diamonds). An interactive version is available at https://iecor.clld.org/languages. Colors distinguish the 12 main clades of Indo-European (other potential clades went extinct without sufficient written record). (B to D) Maps showing alternative hypotheses for the first stages of Indo-European expansion. The hypothesis of an origin in the western steppe (B) contrasts with the hypothesis of an earlier spread with farming (C). The map in (D) shows a hybrid of parts of both hypotheses. Date estimates for the start of divergence within each main clade are given in years before present. Language labels on the hypothesis maps reflect recent end points, not necessarily earlier movements. RESEARCH ARTICLE

Indo-European branches in Europe

The divergence of Indo-European branches in Europe and Asia represents a critical aspect of linguistic and ancestral history. The Germanic, Celtic, and Italic branches split around 4890 years ago, with the Balto-Slavic division happening earlier, approximately 6460 years ago. The separation of the Albanian, Greek, Armenian, and Anatolian branches occurred even earlier, indicating a complex and spread-out timeline of linguistic divergence.

The Hybrid Hypothesis

Through their analysis, Heggarty and colleagues propose a hybrid hypothesis that posits an initial origin of Indo-European languages south of the Caucasus, followed by a northward branch into the Steppe region. This hypothesis aims to reconcile two rival theories: the "Steppe hypothesis," which suggests an expansion out of the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, and the “farming” or “Anatolian” hypothesis, which proposes that Indo-European dispersed with agriculture out of parts of the Fertile Crescent.

Contradictions with the Steppe hypothesis

The Steppe hypothesis, which suggests that all branches of Indo-European originated in the Steppe region, encounters several contradictions. One significant contradiction involves the early branching of Indo-Iranic around 6980 years ago, which does not align with the Steppe hypothesis. Steppe ancestry wasn't discovered until about 3500 years ago in the Gandhara Grave Culture, further complicating the hypothesis. The presence of Steppe ancestry in South Asia is irreconcilable with the earlier separation date for Indo-Iranic, given that Indic and Iranic had already diverged around 5520 years ago.

Additionally, significant branching events within the Indo-European language family further contest the Steppe hypothesis. Seven distinct branches of Indo-European were already established before Steppe ancestry spread into Europe. Notably, the Anatolian, Greco-Armenian, and Indo-Iranic branches demonstrated little or no genetic influx from the Steppe region. Contrarily, CHG/Iranian ancestry, originating south of the Caucasus, was found to spread into the Steppe region, thereby linking past populations in Europe and those south or east of the Caucasus. The spread of Steppe ancestry emerged as a secondary phase, ushering only certain branches into Europe. Interestingly, Steppe ancestry was absent in the Bronze Age Balkans and Early Bronze Age Greeks, making its appearance in Greece and Armenia approximately 5000 years ago. Prior to this, CHG/Iranian-like ancestry had already diffused across regions including Anatolia, the Caucasus, northern Mesopotamia, and southeastern Europe. This CHG/Iranian-like ancestry stands as an alternative candidate for spreading the early branches of the Indo-European languages, offering a unique perspective on our understanding of the propagation of language and ancestry. The earlier estimates for the separation of Indo-Iranic further corroborate this scenario, challenging the validity of the Steppe hypothesis.

The Indo-European Puzzle

Despite the use of advanced linguistic methodologies and phylogenetic analysis, there remains a degree of uncertainty around Indo-European origins. Ancient DNA evidence, although valuable, offers indirect interpretations of language prehistory. Both the Steppe and farming hypotheses have their own strengths and weaknesses. For instance, the median root age for Indo-European is estimated to be around 8120 years B.P., a date not entirely consistent with either hypothesis.

more Linguistic Divergence and Ancient DNA Evidence

New genetic evidence suggests that the Anatolian branch of Indo-European cannot be traced to the steppe. While potential candidate expansions out of the Yamnaya culture are detectable in ancient DNA for other branches, these appear to have had limited genetic impact in Anatolia. Moreover, divergences within Romance and Indic languages are more accurately dated with the new approach, aligning with historical data on the Roman Empire and the divergence from Vedic Sanskrit.

A Hybrid Resolution

Language phylogenetics and ancient DNA suggest a resolution to the Indo-European enigma. The proposed hybrid hypothesis postulates that Indo-European languages originated from a homeland located south of the Caucasus, in the northern Fertile Crescent. From this point, one major branch spread northward onto the steppe, spanning much of Europe. The genetic ancestry associated with Indo-Iranic and primary European branches materialized in southeastern Europe. This hybrid hypothesis diverges from the Steppe and farming theories.

This hypothesis is supported by newer genetic evidence. Steppe ancestry, for instance, is found to have appeared as a secondary phase, carrying only some branches into Europe. Importantly, Steppe ancestry is not found until around 3500 years ago in the Gandhara Grave Culture, a discrepancy with the earlier date for the separation of Indo-Iranic around 6980 years ago. Moreover, a CHG/Iranian-like ancestry, representing an alternative candidate for spreading early branches of Indo-European, had spread across Anatolia, the Caucasus, northern Mesopotamia, and southeastern Europe well before the Steppe ancestry reached Greece and Armenia.

The map in (D) shows a hybrid of parts of both hypotheses. Date estimates for the start of divergence within each main clade are given in years before present. Language labels on the hypothesis maps reflect recent end points, not necessarily earlier movements. RESEARCH ARTICLE

The early Bronze Age predates the spread of "steppe" ancestry, supporting the idea that the Indo-European homeland was located south of the Caucasus. From here, early migrations split Proto-Indo-European into multiple branches. Indo-Iranic emerged as a distinct branch during these early phases of Indo-European divergence, contradicting the Steppe hypothesis, which assumes Indo-Iranic spread via the Steppe and Central Asia.

Another branch reached the steppe directly to the north, establishing the steppe as a secondary homeland for subsequent expansions into Europe and north-central Asia. The specific route of Indo-Iranic's eastward spread remains unclear.

Incorporating insights from ancient DNA research, the hybrid hypothesis suggests a South Caucasus homeland for Indo-European. This idea aligns with observations that Indo-European languages spread concurrently with past population expansions. It's noteworthy that the Anatolian branch did not originate in the steppe.

The origin of other branches remains an open question. While some branches show limited genetic impact from past population expansions, a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses might best account for the enigmatic spread and evolution of the Indo-European language family.

Beyond the Hypotheses

The hybrid hypothesis reconciles the Steppe and farming hypotheses, yet it does not provide a definitive answer to Indo-European origins. The findings by Heggarty et al. underline that the question of the origin of other branches remains, with some branches showing limited genetic impact from past population expansions.

The extensive data collected in the IE-CoR database, combined with improved data collection and coding methods, offer a robust platform for further research. In addition, the use of Bayesian inference for root age estimation and models such as the Covarion model and the uncorrelated relaxed clock as substitution models present a new methodological approach.

Despite the advances, the enigma of the Indo-European languages persists. As the study continues, the hybrid hypothesis provides a unique lens through which to view the complex history of the Indo-European language family. As Heggarty and colleagues highlight, the resolution to the Indo-European enigma lies not in a single theory but rather in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses, providing a nuanced understanding of the past that aligns with the complexity of human history itself.