Unseen until now, a hidden, old Bible fragment was discovered by a historian in the Vatican.

A hidden passage from the Gospel of Matthew, written in Old Syriac and different from what is currently seen in the Bible, has been found by a historian examining a text in the Vatican.

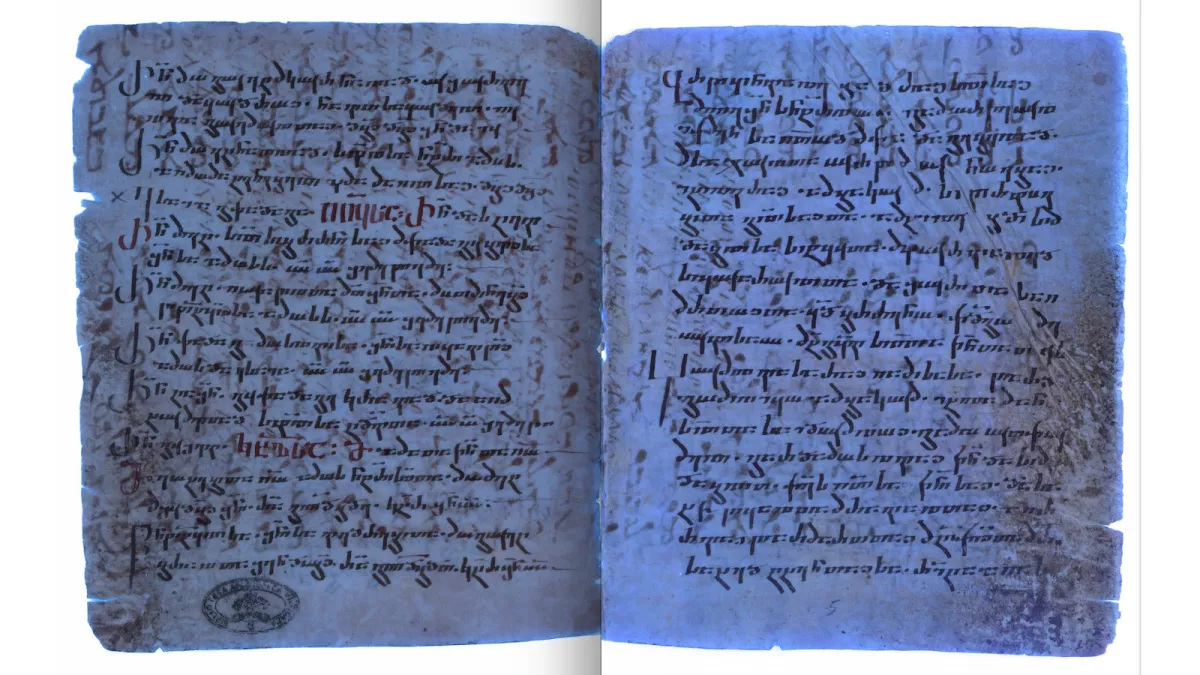

Ultraviolet photography revealed a hidden text containing part of the Gospel of Matthew written in Old Syriac. (Image credit: Image courtesy of Grigory Kessel)

Ultraviolet (UV) photography was used to uncover the alternative gospel. Scribes frequently reused parchments, writing over older manuscripts, because parchment was rare in the Middle Ages, according to a statement from the researchers.

The parchment's most recent writing is in Georgian, while a Greek earlier writing may be found beneath it. But when Grigory Kessel, a researcher at the Austrian Academy of Sciences who specializes in Syriac, looked at UV images from the Vatican library, he discovered yet another layer buried beneath the Greek text.

Matthew 12:1 is partially found in the Old Syriac text. Kessel hypothesized that someone in the sixth century transcribed the phrase onto the parchment. Kessel speculates that the original could have been written in the third century based on the language.

This gospel was probably written sometime in the second half of the first century and is typically credited to the apostle Matthew. Therefore, the recently discovered text is likely 200 years younger than the majority of the gospel.

The verse now reads, "at that time Jesus went through the grainfields on the Sabbath; and his disciples became hungry and began to pick the heads of grain and eat," according to the statement. The recently found Old Syriac text, however, states that the disciples "began to pick the heads of grain, rub them in their hands, and eat them."

According to Kessel, who spoke with Live Science, there is just one other Old Latin-written Gospel manuscript that makes the assertion that the disciples rubbed grain in their hands. If rubbing the grain had any religious significance is unclear.

In an email to Live Science, Sebastian Brock, a retired professor of Syriac at the University of Oxford, said, "This is indeed an exciting discovery, and a brilliant piece of decipherment." Brock observed that the gospels' copies in Old Syriac and Old Latin frequently diverge from other versions. The Middle Ages saw an increasing standardization of the gospels.

These kinds of findings are important for understanding the early development of the New Testament text before it took on the recognized form found in contemporary editions and translations, according to Brock.