The whale escaped, but not unscathed.

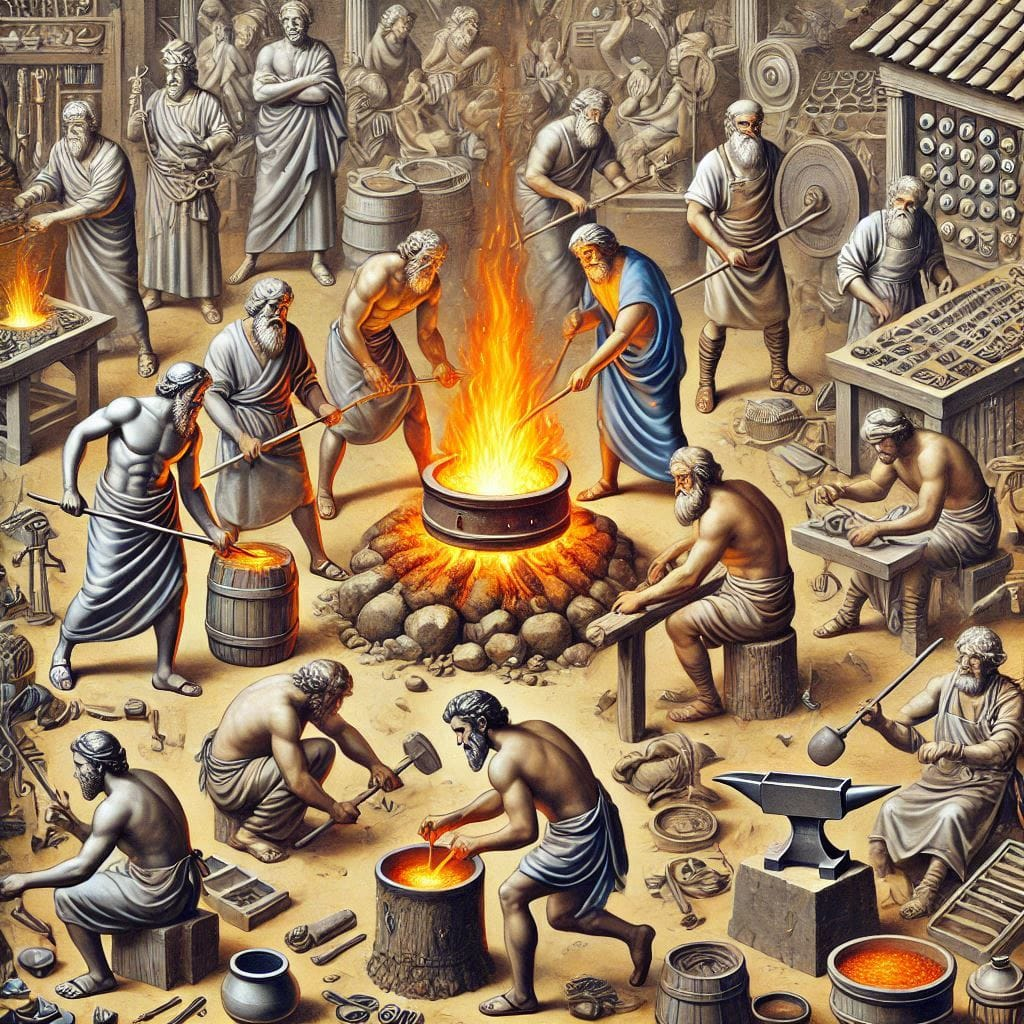

Visual representation of Otodus megalodon’s predatory attack on a small whale, with possible origin of the crushed vertebra. (Image credit: Art by Clarence (Shoe) Schumaker, image courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum)

About 15 million years ago in a warm coastal sea covering what is now southern Maryland, the ocean surface suddenly erupted in a violent upheaval as a shark the size of a five-story building — the mighty and massive megalodon (Otodus megalodon) — launched itself at a whale near the surface, clamping its 250 serrated teeth around the whale's midsection. As the struggling pair broke the surface in a bloody breach, the force of the attack bent the whale's back and caused a violent compression fracture.

That's the scenario proposed by scientists who recently examined two of the whale's fractured vertebrae and one megalodon tooth, which were found close together in Maryland's Calvert Cliffs, a site dating to the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago). The researchers described the whale's injuries — and what might have caused them — in a new study, published online Aug. 25 in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica(opens in new tab).

"We only have circumstantial evidence, but it's damning circumstantial evidence," said Stephen J. Godfrey, a curator of paleontology at the Calvert Marine Museum in Maryland and lead author of the study. "This is how we see the story unfolding," Godfrey told Live Science. "Although there are limitations to what we can claim, and we want the evidence to speak for itself."

The scant remains of what was likely a 13-foot (4 meters) whale, dating to about 15 million years ago, were initially discovered by Mike Ellwood, a Calvert Marine Museum volunteer and fossil collector. It was not possible to determine if the specimen was a toothed whale, a baleen whale or even a large dolphin, but Godfrey was instantly enthralled nonetheless.

"In terms of the fossils we've seen on Calvert Cliffs, this kind of injury is exceedingly rare," he said. "The injury was so nasty, so clearly the result of serious trauma, that I wanted to know the backstory."

Godfrey suspected that he might learn more by looking inside the damaged vertebrae with CT scans, and a local hospital offered to help assess the fossil with modern medical imaging techniques. The scans showed a textbook compression fracture — a type of break in which vertebrae crumble and collapse — that was so distinctive in its pattern as to be instantly recognizable.

"Any radiologist would look at this and recognize the pathology," Godfrey said.

One of two whale vertebrae found in the Calvert Cliffs, with the bottom displaying extensive trauma that occurred during life, not fossilization. (Image credit: Image courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum)

The scientists also discovered that the membrane surrounding the bone, known as the periosteum, had produced new bone after the injury. Regardless of whether the periosteal bone formed to repair the wound, as it often does in humans, or as the result of an infection or arthritis, the growth of new bone post-injury suggests that the whale lived for several weeks after experiencing the fracture.

But as compelling as the megalodon hypothesis may be, other factors could have fractured the whale's vertebrae millions of years ago. Extinct marine megafauna other than a megalodon — such as its close relative Otodus chubutensis, the false mako shark (Parotodus benedenii), the Miocene white shark (Carcharodon hastalis) or even a macroraptorial sperm whale (Physeteroidea) — could have delivered similarly punishing blows. It's even possible that the whale ingested toxic algae and vigorously convulsed until the animal essentially broke its own back, the study authors suggested.

A CT scan shows damage to the vertebra and bone growth that took place after the injury. (Image credit: Image courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum)

But Godfrey thinks a megalodon attack is the most plausible explanation. For one thing, there's the sheer magnitude of the trauma — one vertebra actually telescoped inward from the force of the other vertebra smashing into it. "It's just so over the top in terms of the violence," Godfrey said, adding that it's hard to imagine any seizure or convulsion packing such a punch.

And then there's the megalodon tooth, found alongside the vertebrae. Closer examination of the tooth revealed that its tip broke off during the Miocene, likely after striking something like bone. And while it is possible that a Miocene megalodon may have simply shed its old tooth while swimming over a long-dead whale carcass, or lost it while hunting an injured whale and feeding on its remains, it is tempting to reconstruct a scene in which the apex predator of the day blunted and ultimately lost its tooth while dealing the compression fracture itself.

"We don't know the full repertoire of predatory techniques that megalodon could have employed, but it's possible that, like living sharks, they ambushed their prey from below," Godfrey said. During a high-energy breach with prey between its jaws, he explained, the megalodon could have easily flexed the whale's backbone against gravity with enough force to create the observed injuries.

But Godfrey isn't ruling out alternative explanations. "Our paper covers the breadth and scope of the conditions that could have caused this kind of damage, and hopefully that will spur further research," he said. "These are amazing stories. We get to tell the initial story, but whether that turns out to be the best explanation really remains to be seen."

Originally published on Live Science.