Polyzalos, the tyrant of Gela and brother of Hieron of Syracuse, celebrated his chariot race victory by dedicating an elaborate monument to Apollo at Delphi. This grand offering—a quadriga (four-horse chariot) with Polyzalos himself aboard, accompanied by a charioteer—once stood proudly at the sacred site. But in 373 BCE, a devastating rockslide from the Phaedriades cliffs destroyed much of the sanctuary, crushing the bronze horses, the chariot, and the rider. Only the charioteer survived.

And yet, art has its own logic in destruction. While we lost a remarkable composition crafted by master bronze-workers—renowned for their depictions of athletic triumphs in Elis and Delphi—what remained became even more captivating. The charioteer, now alone without his horses, without his chariot which once concealed him up to the waist, and without the noble figure beside him, stands as one of the most intriguing and evocative figures in ancient sculpture. His very isolation stirs the imagination—of the lost companions, the unknown sculptor. The work was completed by two creators: the artist and time. And time, in this case, proved to be an inspired collaborator.

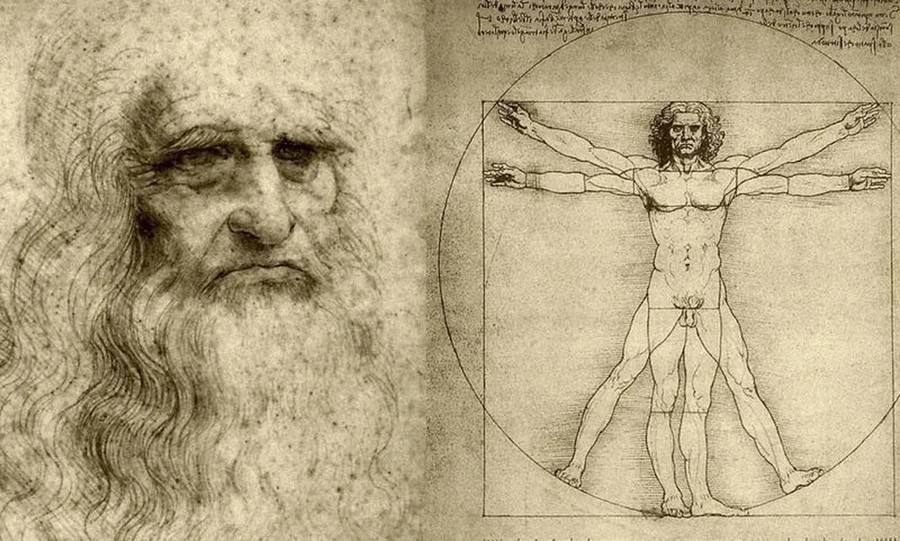

Mastery in the Details

What remains most striking are the charioteer’s lower limbs—bare feet that were never meant to be seen. Even knowing they would be hidden behind the chariot, the sculptor gave them meticulous attention, carving the feet and legs with such grace and anatomical precision that they remain among the finest examples in all of Greek sculpture. Each toe is individually rendered, the ankles defined, the shins rising in subtle curvature. The soles plant firmly, grounding the figure with calm assurance. These elements together create a distinct harmony—an archaic purity that resonates with timeless aesthetic appeal.

A Moment of Poise After the Storm

In the charioteer's stillness, we glimpse the frenzy that came before. There is a quiet grandeur—a body soothed by victory. This is the moment after the contest, during the slow ceremonial parade when the champion, motionless in his chariot, receives the jubilant applause of the crowd. The statue captures this pause, this reward. It stands straight, both feet flat, robed in a long, heavy chiton with deep, unbroken folds. His posture is disciplined, composed—an embodiment of dignity and triumph.

Two subtle motions give the figure its life. One is the slight lean of the body, and even more so of the head, to the right—a tilt that suggests introspection or calm elation. The expression on his face, eyes cast with a serene intensity, conveys a quiet pride. The lips, gently parted; the nostrils, flaring with the breath of exertion; the brows, arching in perfect curves—all contribute to a sense of vivid realism.

Most astonishing are the eyes: crafted with inlays of different metals set against a light-colored enamel base, they seem to shimmer with thought and emotion. They reflect victory—not as spectacle, but as lived experience. A triumph captured in bronze.

A Sculptural Mystery

The Charioteer is youth in sculpted form—youth touched by light, shaped by discipline and purpose, yet brimming with vitality. No other ancient work combines such poised stillness with freshness, such formal strength with human softness. The chiton reveals a powerful right arm, and the relaxed hand that holds the reins displays a musical elegance in its curves.

But who was the artist behind this marvel? Some suggest Pythagoras of Rhegion, others Kritios or Kalamis. We may never know. What we do know is that this masterpiece emerged in a pivotal moment—the end of the Archaic period, just before the dawn of Phidias. Like a tree bursting into bloom just before decline, archaic art gave us a few final works of concentrated beauty, full of mystery and emotional depth.

The Charioteer Rediscovered

The Charioteer, the most iconic piece in the Delphi Archaeological Museum, was unearthed on April 16 (28, New Style), 1896, during the “Grande Fouille”—the great excavation carried out by the French School at Athens between 1892 and 1901, under official license from the Greek government.

The statue was originally part of a larger dedication made by Polyzalos to commemorate (most likely) his victory at the Pythian Games, either in 478 or 474 BCE. The offering included the four-horse chariot, the charioteer, and two stable hands who likely walked beside the horses. It was all likely destroyed by the great earthquake of 373 BCE.

No surviving records definitively attribute the Charioteer to any known sculptor. Over the years, scholars have linked it with Pythagoras of Rhegion, Kritios, or Kalamis, but without consensus. What remains clear is that this bronze figure, both grounded and exalted, marks the final moment before the classical bloom—a "pre-Phidian" miracle in bronze.