The Many Faces of the Swastika: Understanding Its Ancient Legacy and Modern Impact

The swastika is a symbol that transcends time, geography, and culture, embodying a myriad of meanings and significances across the globe. Its origins, deeply rooted in ancient civilizations, reveal a complex narrative of religious symbolism, cultural exchange, and historical transformation. It is an ancient symbol that has been found in various archaeological contexts across Europe, Mesopotamia, the Eurasian Steppe, and India, among other locations. Its presence in such a wide geographical area and its usage dating back to prehistoric times make it a subject of significant interest for historians, archaeologists, and scholars studying the spread of cultures and ideas. This exploration delves into the swastika's journey from its earliest appearances to its modern-day interpretations.

Oldest Known Artifacts and the ancient history of swastika

The swastika's story begins thousands of years ago, with some of the earliest known artifacts dating back to the Paleolithic era. A striking example is a bird figurine found in Mezine, near Kiev, Ukraine, adorned with a swastika pattern, estimated to be up to fifteen thousand years old. This discovery, among others, underscores the symbol's ancient roots and its widespread use in prehistoric times.

According to Joseph Campbell, the earliest known swastika is from 10,000 BCE – part of "an intricate meander pattern of joined-up swastikas" found on a late paleolithic figurine of a bird, carved from mammoth ivory, found in Mezine, Ukraine.

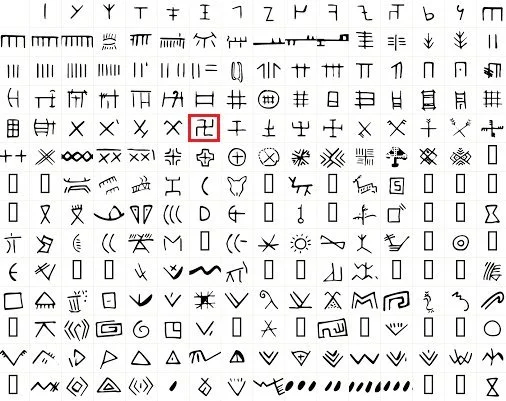

Other old, well-known artifacts bearing the swastika symbol date back to the Neolithic era. One of the earliest examples can be found in the Vinča culture, which flourished between 5500 and 4500 BCE in the Balkans, particularly in what is now Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Artifacts from this era, including pottery and figurines, showcase the swastika's role in Neolithic societies, hinting at a deep-seated cultural significance that predates many contemporary interpretations.

Another early example comes from the Indus Valley Civilization, particularly from artifacts dated around 3000 BCE. This civilization spanned across what is now Pakistan and northwest India, and the presence of the swastika here indicates its early significance in South Asian cultures as well. In the Indus Valley Civilization, the swastika was a prominent symbol, evident on seals and pottery. This early appearance in South Asia illustrates the symbol's integral role in the religious and cultural practices of one of the world's earliest urban societies. The right-facing variant of the swastika, in particular, was associated with auspiciousness and well-being, reflecting its sacredness in the region's spiritual life.

All symbols represent in Vinca culture. Swastika in a red square.

The swastika's significance was not confined to any single interpretation. In Hinduism, the right-facing swastika symbolizes the sun, prosperity, and good luck, while its left-facing counterpart, the sauvastika, represents the night or tantric aspects of Kali. This duality underscores the symbol's complex role in Indian religions, where it remains a revered emblem of divinity and spirituality.

Buddhism and Jainism too adopted the swastika, imbuing it with representations of auspiciousness, eternity, and the spiritual journey. In Buddhism, it symbolizes the Buddha's footprints as a mark of sacredness and a guide to enlightenment. Jainism associates the swastika with the seventh Tirthankara, Suparshvanatha, highlighting its spiritual significance and the ethical principles it embodies.

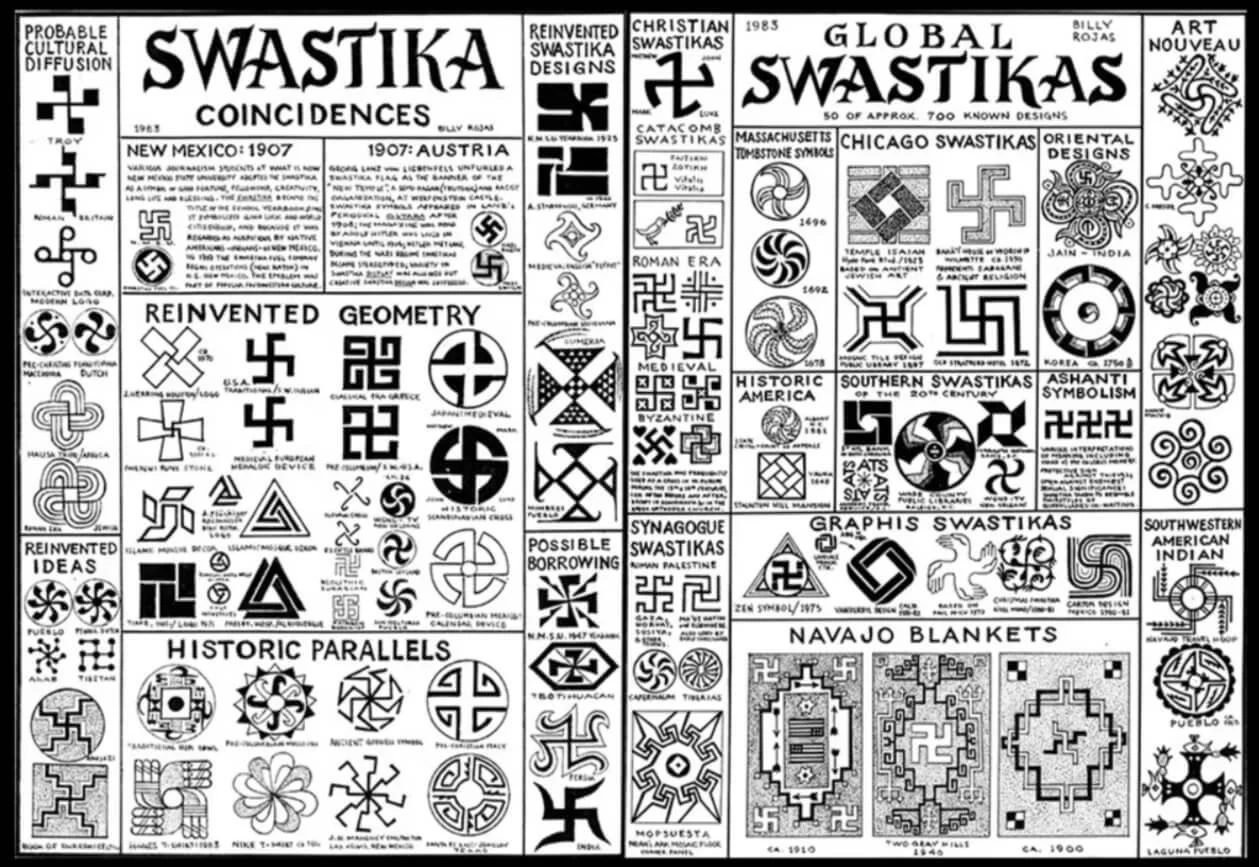

The symbol's diffusion across cultures and continents is a testament to its universal appeal and adaptability. From its use in ancient Greek and Roman mosaics to its significance in Norse mythology as a representation of Odin, the swastika's geometric simplicity and symbolic depth facilitated its adoption by diverse cultures. This widespread use suggests a shared human inclination towards symbols that embody life, continuity, and the cosmic order.

Swastika seals from Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan, of the Indus Valley civilisation, circa 2,100–1,750 BCE, preserved at the British Museum.

The Navajo and other Native American groups used the swastika in ceremonial contexts, further demonstrating its universal appeal. These uses highlight the symbol's capacity to convey meanings of fertility, prosperity, and the cyclic nature of life, themes that resonate across different belief systems and geographical regions.

Interpretation and Diffusion

The widespread distribution of the swastika symbol across such diverse regions raises questions about its significance and the means by which it spreads. There are several theories regarding this:

1. Indo-European Spread: One theory suggests that the diffusion of the swastika might be connected to the migrations of Indo-European peoples from the Eurasian Steppe. The Kurgan hypothesis, for instance, posits that the Proto-Indo-Europeans from the Pontic-Caspian steppe spread their culture and languages westward into Europe and eastward into Asia, potentially carrying with them symbols such as the swastika. This could explain its presence across a broad geographic area.

2. Anatolian Neolithic Farmers: Another hypothesis argues for the spread of agricultural and cultural practices (including symbolic systems) from the Neolithic Anatolian farmers into Europe. However, the evidence of the swastika in both the Vinča culture and the Indus Valley Civilization predates significant Indo-European migrations, according to this theory, making a direct link less clear.

3. Trade and Cultural Exchange: The diffusion of the swastika can also be attributed to extensive trade networks and cultural exchanges between ancient civilizations. These interactions would have facilitated the spread of symbols, ideas, and technologies without implying direct migration or conquest. The symbol’s presence in diverse cultures could therefore reflect shared human motifs or universals rather than the spread of a single cultural group.

The Samarra bowl, from Iraq, circa 4,000 BCE, held at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction. Dbachmann - Self-photographed

Twentieth-Century Ideological Turn

However, the symbol's appropriation by far-right Romanian politician A. C. Cuza before World War I as a symbol of international antisemitism and its subsequent adoption by the German Nazi Party as an emblem of the Aryan race dramatically altered its perception in the West. This appropriation has led to the swastika being predominantly associated with Nazism, antisemitism, white supremacism, and evil in the contemporary Western context. This shift has overshadowed the symbol's ancient and positive connotations, leading to its prohibition in several countries, including Germany, where its public display is restricted by law.

The swastika's history took a final dark turn in the 20th century with its appropriation by the National Socialist Party in Germany. This adoption transformed the swastika into a symbol of racial hate and the atrocities of World War II and the Holocaust. The profound impact of this period has overshadowed the swastika's ancient and diverse heritage in much of the Western world, altering its perception and use significantly.

Cuza's use of the swastika was part of a broader European interest in ancient symbols and their meanings, which was intertwined with rising nationalist sentiments and the search for symbols that could represent national identity and purity. This period saw various nationalist movements across Europe exploring ancient symbols, including the swastika, to serve as emblems of their cause, drawing on their supposed connections to the ancient past and Indo-European heritage.

While Cuza's adoption of the swastika is a documented example of the symbol's use by a political movement before the Nazis, it did not have the same widespread impact or global recognition as the Nazi Party's appropriation of the symbol. The Nazis' use of the swastika from 1920 onwards, and especially during their rule from 1933 to 1945, firmly established the symbol as a representation of their ideology, leading to its stigmatization in the post-World War II era.

Despite its controversial modern history, the swastika continues to hold sacred significance in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Its enduring presence in these religions underscores the complexity of symbols and their meanings, reminding us of the swastika's original connotations of well-being, auspiciousness, and spiritual depth. This duality highlights the importance of context and interpretation in understanding cultural symbols.

While the swastika's presence in prehistoric artifacts across Europe, Mesopotamia, the Steppe, and India is well documented, determining the oldest artifact definitively is challenging due to the variety of contexts in which the symbol appears. The diffusion of the swastika likely results from a complex interplay of factors, including migrations, cultural exchanges, and the spread of ideas and technologies through trade networks. Rather than proving a singular theory about Indo-European spread from the steppe or from Anatolian Neolithic farmers, the evidence suggests that connections and interactions between different cultures and regions played a significant role in the distribution of the swastika symbol. This complexity highlights the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations and the multifaceted nature of cultural transmission.