If you have a long second toe, you might have heard it called “Greek foot” or “flame foot”—a distinct trait where the second toe is longer than the big toe and the others. Though often linked with Greek ancestry, this trait is actually an inherited genetic variation that isn’t confined to any one ethnicity.

What Is "Greek Foot" and Where Did It Come From?

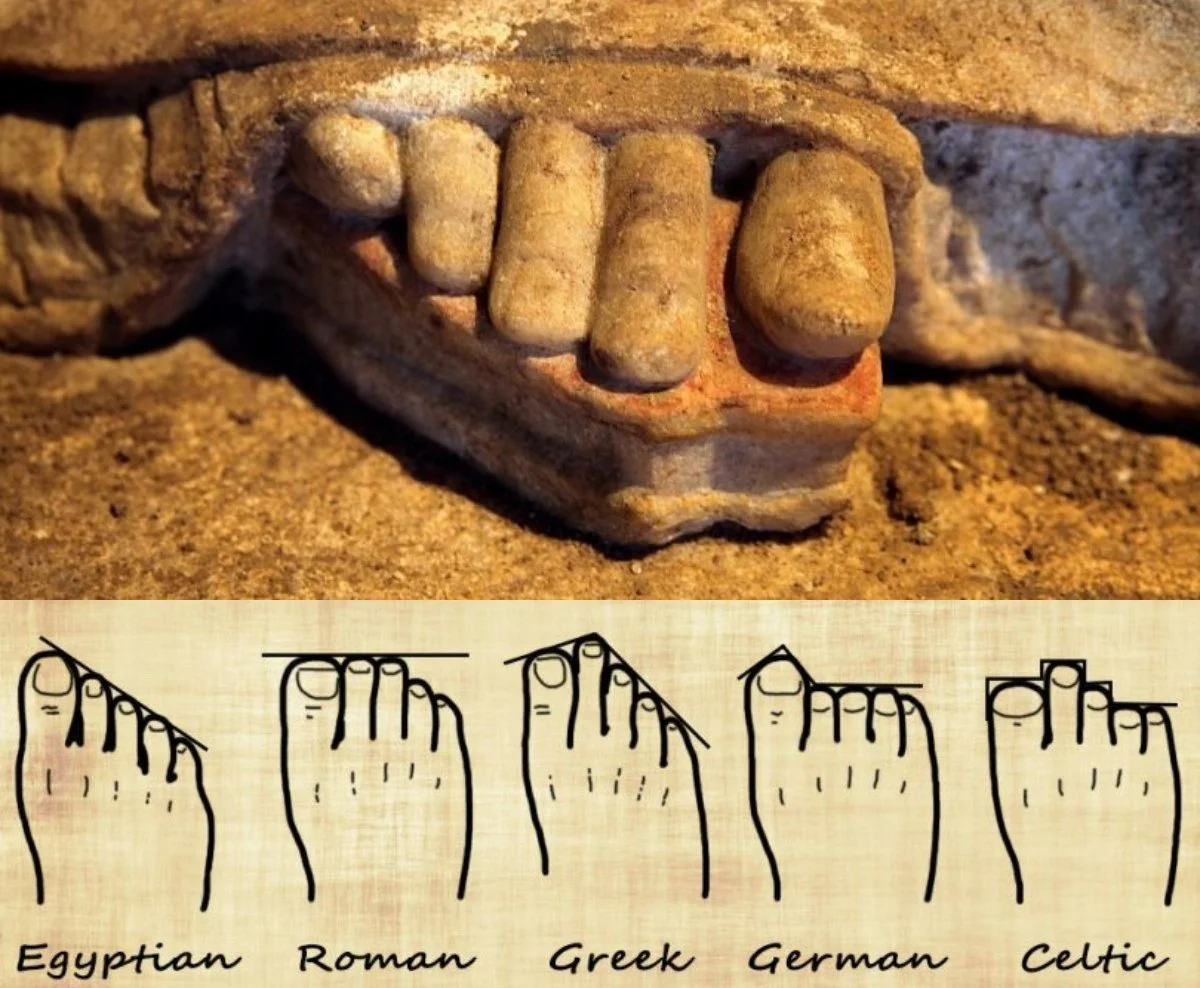

This foot shape, with a prominent second toe, is known scientifically as Morton’s toe. Named after the American orthopedist Dudley Morton, it affects the way weight is distributed across the foot and can sometimes lead to specific foot issues due to this altered weight distribution. Interestingly, this type of foot structure was idealized in Greek art and sculpture, seen in iconic figures like the Caryatids and other famous statues.

The concept of the “Greek foot” can be traced back to the aesthetic ideals of Ancient Greece. The Greeks considered this foot shape harmonious, and it became a defining feature in their depictions of the human form. This visual ideal was not just an artistic choice but also found its way into Greek architecture and geometry, influencing proportions in design and even economic practices. The famous Caryatids—stone maidens holding up the Erechtheion in Athens—are perfect examples, each displaying this classic "Greek toe."

Greek Foot in Genetics: An Inherited Trait, Not Greek Ancestry

Despite its association with Greek heritage, having a “Greek foot” is more about genetics than lineage. Studies show that this foot shape is actually an X-linked recessive trait, meaning the gene responsible for the longer second toe is located on the X chromosome. This trait can be passed down through families, but it isn’t exclusive to people of Greek descent. Populations all over the world have this feature, including groups as far-flung as the Ainu of Japan and certain indigenous groups in South America.

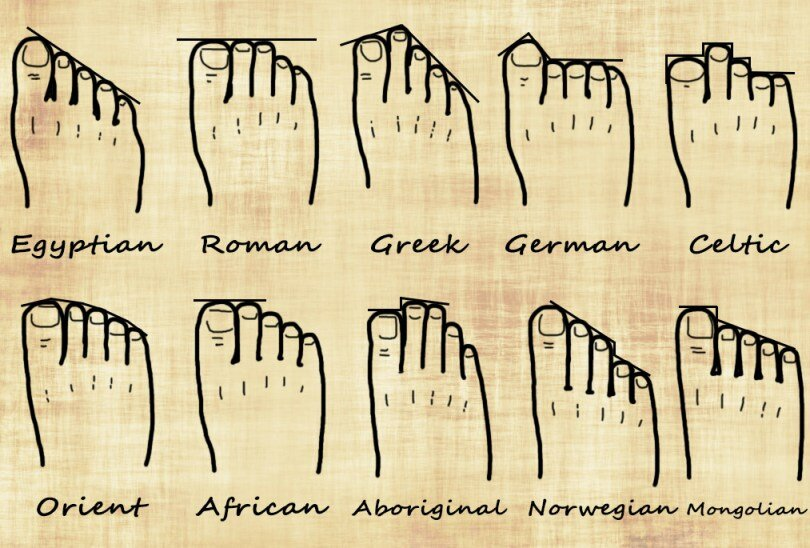

The Prevalence of Greek Foot Across Cultures

Estimates on how common “Greek foot” actually is vary, with research suggesting prevalence rates between 5% and 30% worldwide. This wide range might be due to how different populations inherit the trait and how often it’s passed along. Despite its name, “Greek foot” is not unique to Greece and has even been observed in Celtic ancestry, sometimes referred to as “Celtic foot.”

So, if you have a long second toe, you share a trait with various cultures and ancient artistic ideals. It’s an inherited quirk rather than a genealogical signature of Greek heritage.

The Physical Impact: Does Greek Foot Give You an Advantage?

Having a longer second toe doesn’t just alter appearance—it can also affect foot mechanics. Morton’s toe can sometimes lead to discomfort due to uneven weight distribution. Those with Greek foot may experience specific types of foot pain or even calluses if they frequently wear ill-fitting shoes.

However, some suggest that Greek foot might offer an advantage in certain athletic activities. A 2004 study showed this trait was more common in professional athletes, potentially because it changes balance and how pressure is applied to the foot. This might mean a slight edge in sports that involve a lot of running or jumping, though this theory needs further research.

A Universal Trait in a Unique Context

Greek foot, while widely recognized for its prevalence in Greek art and sculpture, isn’t limited to Greece or even Europe. It's a fascinating example of how genetic traits can cross boundaries, showing up in people across continents and cultures. So, the next time you catch a glimpse of a statue with a pronounced second toe, remember: it’s not just a Greek trait, but part of a global genetic tapestry.