Exploring the Polyglot World of the Hittite Empire: The Eight Languages of the Boğazköy Tablets

The Boğazköy Archive, discovered amidst the ruins of ancient Hattusa (now Boğazköy), stands as a remarkable testament to the Hittite civilization, a dominant political force in the Middle East during the 2nd millennium B.C. This vast collection of nearly 25,000 cuneiform tablets is the primary source of our knowledge about the social, political, commercial, military, religious, legislative, and artistic facets of this era in Asia Minor and the broader Middle East.

Key Contents of the Archive

The Boğazköy tablets cover an array of subjects, from royal annals, chronicles, decrees, and treaties like the famous Treaty of Quadesh with Egypt to legal codes, mythological texts, lists of rulers, diplomatic correspondence, deeds, codes of laws, court records, mythological and religious texts, astrological predictions, Sumero-Akkado-Hittite dictionaries, and even practical guides on horse breeding. This variety provides a comprehensive view of the Hittite civilization's complexity and sophistication. The overwhelming majority of texts found in the Boğazköy archive belong to the New Hittite period (14th and 13th centuries B.C.), and only a small number of them (including the early version of the laws) go back to the 17th and 16th centuries B.C.

Lion Gate, Hatussa

Archaeological and Linguistic Significance

The discovery and ongoing study of these tablets, initiated by H. Winckler together with Greek-Ottoman archeologist Theodore Makridi Bey, from 1906 to 1912, have significantly advanced our understanding of the Hittite civilization and its interactions with neighboring cultures. The linguistic findings, in particular, have revolutionized Indo-European studies, revealing previously unknown languages and dialects within this family.

The Linguistic Landscape of the Boğazköy Archive

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Boğazköy Archive is its linguistic diversity, which encompasses texts in eight different languages. This polyglot nature highlights the cultural and political influence of the Hittite Empire.

1. Cuneiform Hittite: The role of Cuneiform Hittite in the Hittite Empire cannot be overstated. As the predominant language of the Boğazköy Archive, it offers a direct insight into the administrative, legal, and diplomatic workings of the empire. This version of the cuneiform script, adapted from the earlier Akkadian system, was a vital tool for recording laws, treaties, and royal decrees, serving as the backbone of governance and order in the Hittite state. Its use in diplomatic correspondence, especially in treaties such as the Treaty of Quadesh, underscores its significance as a language of international relations in the ancient Near East.

2. Akkadian: Serving as one of the main languages of the archive, these represent the administrative and diplomatic lingua franca of the ancient Near East. Akkadian, an ancient Semitic language, originated in Mesopotamia around 2500 BC and was extensively used for administration, diplomacy, and literature. Akkadian is divided into two major dialects: Assyrian and Babylonian. It was written using the cuneiform script and is of great historical significance, providing insights into ancient Mesopotamian civilization and culture. Akkadian's influence declined around the 1st millennium BC but left a lasting impact on subsequent languages in the region.

3. Sumerian: A dead language by 1200 B.C., Sumerian's inclusion indicates its continued scholarly significance. The ancient non-Indo-European language of the Sumerian civilization was the first to develop the cuneiform script, which, although already dead at that time, was still being taught.

4. Hurrian: Neither Indo-European nor Semitic, Hurrian reflects Mitanni's influence on the Hittite Empire. It was the language of the Land of the Mitanni, to the east of the Hittite Empire, a significant cultural and political group in the region encompassing parts of modern-day Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. The language is known from texts dating from around 2300 BC to the first century AD. Hurrian played a crucial role in the cultural and political tapestry of the area, especially in the context of its interactions with neighboring civilizations like the Hittites and Assyrians. The language's structure and vocabulary remain a subject of study for linguists, offering insights into the diverse linguistic landscape of the ancient Near East.

5. Luwian: An Anatolian Indo-European language probably spoken in western Anatolia, closely related to Hittite and possibly a precursor to Lycian. The Luwian language, part of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European family, played a crucial role in the geopolitical dynamics between the Hittite Empire and the independent states of western Anatolia during the Bronze Age. As a language closely related to Hittite, Luwian served as a linguistic bridge, facilitating diplomatic and cultural exchanges between the Hittites and their western neighbors. The presence of Luwian in the Boğazköy Archive, especially in texts related to western regions, indicates its importance in maintaining relationships and asserting influence over these independent states. Luwian's use in regional administrative and diplomatic documents reflects its status as a regional lingua franca, essential for the negotiation of treaties, trade agreements, and alliances.

6. Palaic: Palaic, an ancient Indo-European language, was one of the lesser-known members of the Anatolian language family, alongside Hittite and Luwian. It was primarily spoken in the region of Pala in north-central Anatolia, now part of modern Turkey. Known mainly from cuneiform tablets of the Boğazköy Archive, Palaic's use seems to have been largely religious, dedicated to ritual and liturgical texts. The language provides a glimpse into the linguistic diversity of ancient Anatolia and the religious practices of its people, but much about Palaic remains obscure due to the limited number of texts available.

7. Hattic (Proto-Hittite): A non-Indo-European language, mainly used in ritual texts, offers a window into the religious practices and beliefs of the Hittites. It was primarily used by the Hattians, indigenous inhabitants of central Anatolia. Primarily known from Hittite texts where it is used in religious contexts, Hattic is distinctive for its unique vocabulary and structure, differing significantly from the surrounding Indo-European languages. Despite its limited corpus, Hattic is crucial for understanding the cultural and linguistic prehistory of Anatolia.

8. An Unidentified Language: The eighth language, which is different from the others, has not yet been precisely identified. The only evidence we have is that it contains some Indo-European terms that correspond to a treatise on equestrian art written in Hittite by Kikkuli, a Hurrian from the Land of the Mitanni. There is a possibility that this is the new Anatolian language that linguists have identified as Kalasma.

Anatolia's Linguistic Mosaic: Unraveling the Indo-European and Non-Indo-European Language Blend

The Anatolian languages, a group of now-extinct languages once spoken in ancient Anatolia, have long been shrouded in mystery, particularly to those outside the academic community. The 20th and 21st centuries witnessed a renaissance in the study of these languages, propelled by archaeological discoveries like the Boğazköy Archive. Prior to these findings, knowledge of these languages was limited and fragmented. The decipherment of cuneiform scripts and the unearthing of texts in Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic, among others, revolutionized our understanding of these ancient tongues. Linguists and historians have used comparative methods, drawing parallels with other Indo-European languages, to piece together their phonology, grammar, and vocabulary. This linguistic detective work has been augmented by advancements in technology, including digital analysis and database compilation, allowing for more nuanced and comprehensive interpretations.

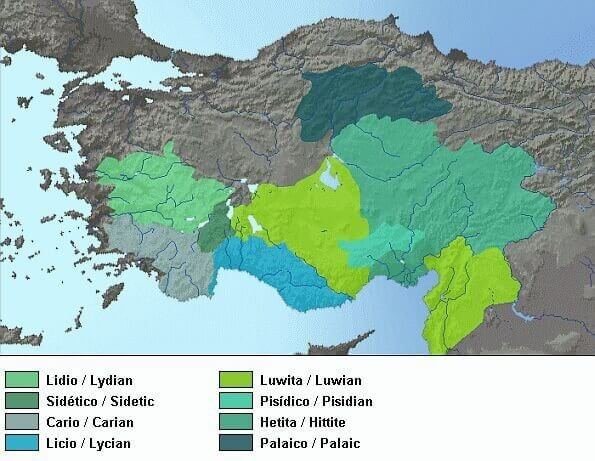

Anatolian languages map

These efforts have not only shed light on the linguistic landscape of ancient Anatolia but also provided insights into the historical interactions, migrations, and cultural exchanges in the region. The study of Anatolian languages has thus transformed from a niche academic pursuit into a key component of understanding the ancient world's complexity.

In ancient Anatolia, a fascinating linguistic tapestry emerged from the mix of Indo-European and non-Indo-European languages. This region, a crossroads of cultures and peoples, featured Indo-European languages like Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic alongside non-Indo-European languages such as Hattic and Hurrian. This linguistic diversity reflects Anatolia's role as a melting pot of different civilizations, where a variety of ethnic and linguistic groups interacted, traded, and coexisted, contributing to the rich cultural and historical heritage of the area.

Cuneiform treaty between Hittite ruler Hattushili III and Ramses II, 13th cent. BCE; Pergamon Museum, Berlin

The Boğazköy Archive is not just a collection of ancient texts; it's a cultural and linguistic mosaic that gives us a detailed picture of the Hittite Empire and its interactions with the ancient world. The diversity of languages in the archive reflects the cosmopolitan nature of Hattusa, mirroring the complexity and interconnectedness of ancient civilizations. As studies continue, the archive promises to further illuminate the rich tapestry of human history and language.