In the intricate tapestry of European languages, the predominance of the Indo-European (IE) language family is both profound and extensive, encompassing a vast array of tongues from the Romance languages of the south to the Germanic and Slavic languages of the north. However, nestled within this linguistic landscape are outliers—languages that do not belong to the Indo-European family, yet have managed to persist through the ages, particularly in Southern Europe. Among these, the Basque language, ensconced in the Pyrenees region, stands out as a remarkable enigma, offering a fascinating glimpse into the survival of non-IE languages in an Indo-European-dominated continent.

The survival of non-IE languages in Southern Europe can be attributed to several factors, including their proximity to the literate Mediterranean world. This geographical advantage may have played a crucial role in preserving these languages, as it facilitated interactions with advanced civilizations and cultures, thereby enabling them to maintain their distinct linguistic identities amidst the encroaching Indo-European languages. Additionally, historical migration patterns and cultural assimilation processes have likely contributed to the persistence of these languages, as they adapted and evolved in response to the changing demographic and cultural landscapes of Southern Europe.

Cultural and linguistic changes in ancient Iberia and Northern Europe further elucidate the persistence of non-IE languages. While ancient Iberia witnessed a significant replacement of its male lineage, the continuity of neolithic farmer ancestry ensured the survival of older linguistic elements. Conversely, in parts of Northern Europe, such as Britain, the neolithic population underwent a drastic replacement, possibly due to factors like disease or famine, during the Bronze Age. This stark contrast highlights the varied historical trajectories that influenced linguistic survival in different regions of Europe.

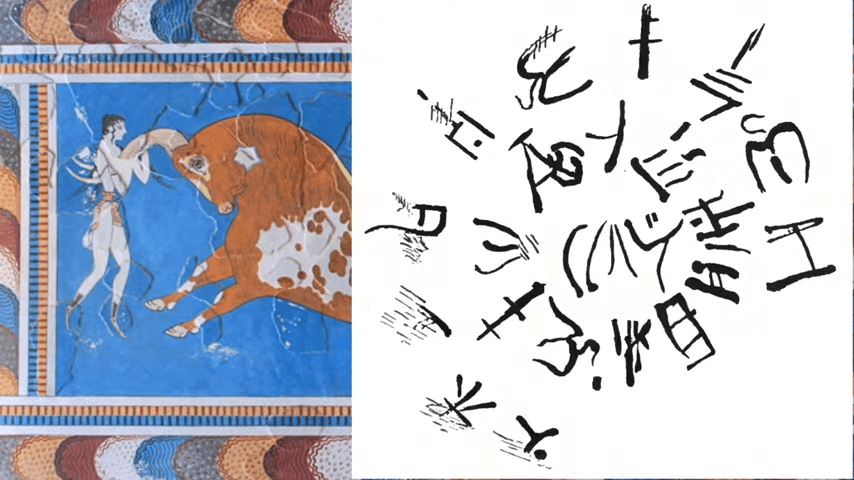

The persistence of non-IE languages in southern Europe is also linked to the survival of old populations in isolated areas. For instance, Minoan, an ancient language that thrived on Greek islands like Crete, and Etruscan, the language of the first mainland Italian civilization, are prime examples of how isolated communities could preserve their linguistic heritage over millennia. These languages not only survived but also influenced subsequent civilizations, demonstrating the resilience and impact of non-IE linguistic traditions.

The influence of local and Mediterranean cultures on non-IE languages in Southern Europe is another factor contributing to their persistence. For instance, Eastern Mediterranean cultures had a significant influence on the Etruscans, who according to some authors, were originally from the East. Similarly, ancient Sardinian languages may contain a pre-Indo-European substratum related to Basque, suggesting the existence of a West Mediterranean language family that has withstood the test of time.

The advanced societies of Bronze Age Sardinians and the possible survival of languages spoken by Neolithic Aegean farmers further underscore the resilience of non-IE languages. The Basque language, in particular, stands as a testament to this enduring linguistic legacy, being the only extant non-Indo-European or Uralic language in Europe today.

The synthesis of pre-Indo-European or proto-Indo-European and Indo-European cultures in southern Europe has played a pivotal role in the survival of older Iberian languages. The assimilation of early Indo-European-speaking newcomers into the pre-existing cultures, coupled with the adaptation of language, facilitated the preservation of these ancient tongues. This synthesis not only ensured the survival of non-IE languages but also enriched the cultural and linguistic diversity of Southern Europe, allowing these ancient languages and cultures to be carried into the historical period.

In conclusion, the persistence of non-IE languages in Southern Europe is a multifaceted phenomenon rooted in geographical, cultural, and historical factors. From the enigmatic Basque language to the ancient tongues of the Minoans and Etruscans, these languages offer a window into the past, revealing the complex interplay between migration, assimilation, and survival. As living relics of Europe's diverse linguistic heritage, they remind us of the enduring power of language to connect us to our ancestors and the stories that shaped our world.