BY HAARETZ

The mosaic more than 1,500 years old cites the church’s donor and a plea for intercession that shores up the case of el-Araj as Bethsaida and the basilica as the Church of the Apostles

An inscription with a plea to St. Peter found at the archaeological site of el-Araj strongly supports the case that this is the lost city of Bethsaida and that the basilica there is the Church of the Apostles, a discovery likely to further buoy Christian tourism at the Sea of Galilee.

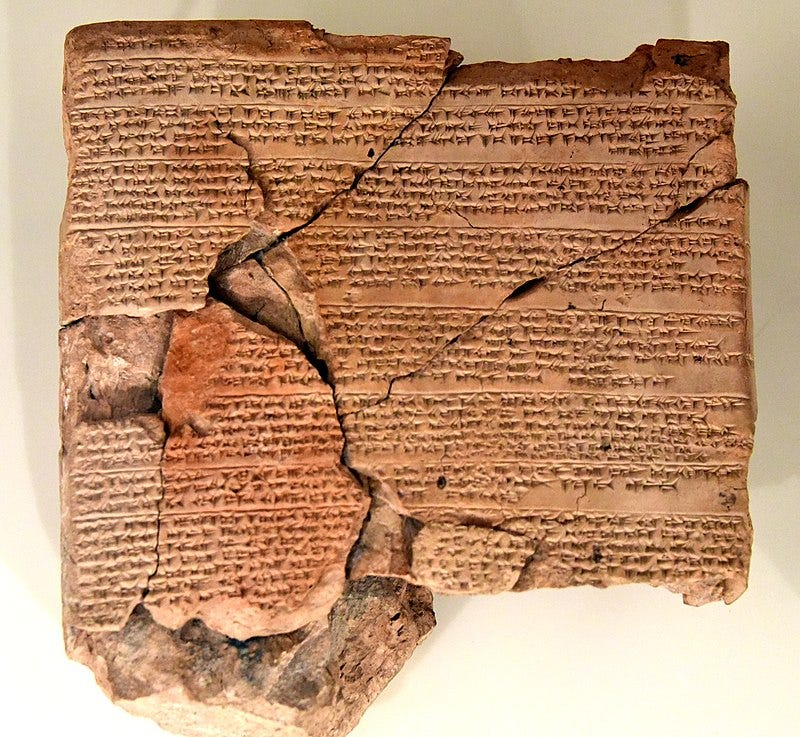

The mosaic was filthy, as is the case with inscriptions buried in silt for more than 1,500 years. Cleaning it off in the blistering heat of this summer’s excavation season at el-Araj – right by the Ottoman mansion Beit HaBek – was the season’s highlight, say archaeologists Prof. Mordechai Aviam and Prof. R. Steven Notley.

A mosaic floor found in the remains of what archaeologists believe is a Byzantine church standing over the home of biblical figure St. Peter and his brother, Andrew. (El Araj Expedition)

El-Araj is on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee and isn’t the only candidate for the biblical village of Bethsaida on which the Roman polis of Julias arose. The New Testament is inconsistent about the abode of Peter and his brother Andrew, but the evidence points to Bethsaida as their home, not the fishing village of Capernaum, many researchers say.

Among the highlights at el-Araj, the archaeologists found Roman-period ruins, homes from the Jewish village – and the ruins of a fifth-century Byzantine basilica.

For years, since discovering an ancient church at el-Araj, the archaeologists had dearly hoped to find a dedicatory inscription, as was typical of Byzantine churches. Now they have.

The inscription starts with “Constantine, the servant of Christ.” This refers to the donor to the church, in keeping with Byzantine tradition of dedicatory mosaics. It isn’t a reference to Constantine, the first Holy Roman emperor to embrace Christianity, the archaeologists explain.

Then comes the exciting bit: The inscription goes on to petition the “chief and commander of the heavenly apostles” for intercession, according to Prof. Leah Di Segni of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Prof. Jacob Ashkenazi of Kinneret College in the north.

Who is this chief and commander? Simon Peter was the first to declare that Jesus was the messiah (Matthew 16:16), and so was considered chief of the Apostles, according to tradition. His prominence is demonstrated by the construction of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, which was put up over his grave.

Chief and commander of the heavenly apostles is how the Byzantine Christians referred to Peter and only to him, not to any other apostle, say Aviam, professor at Kinneret College, and Notley, professor at Nyack College in New York and the dig’s academic director.

So here we have an inscription, framed with a round medallion made of two lines of black tesserae in the Byzantine style, that all but explicitly mentions St. Peter – in an early church dating to the fifth century in a Roman-Jewish city on the banks of the northern Sea of Galilee.

During the next excavation season in October, the archaeologists are keen to find an inscription to Andrew. Since he’s also supposed to have lived in Bethsaida, the church would presumably have been dedicated to them both.

The dedicatory inscription and plea to Peter (the first pope, in Catholic tradition) were part of the mosaic floor in the church’s sacristy, which, in Byzantine fashion, was decorated with floral patterns. For more information on the inscription we’ll have to wait, but the professors promise that it’s coming.

The mosaic floor of the Church of the Apostles, near the Sea of Galilee.

(Mordechai Aviam/Courtesy)

How Bethsaida was lost

Does this close the case that Aviam and Notley have found the biblical city of Bethsaida, as they have argued since 2017, and the Church of the Apostles – a more recent postulation?

“I would say yes on both,” Notley says. “I think this is clear evidence that the site we’re excavating is the church referred to by St. Willibald [in the eighth century] as the church built over the house of St. Peter and Andrew.”

It bears clarifying that the archaeologists aren’t claiming that the Church of the Apostles really was built on the homes of Peter and Andrew. They’re claiming to have found Bethsaida and the Church of the Apostles, and if it was built in the “right” place, we don’t know.

At least one reason Bethsaida was lost to posterity is that the Sea of Galilee – widely known as Lake Kinneret in Israel – is an inland lake that rises and falls. In fact, the archaeological site was underwater after heavy rain in 2020.

Bethsaida was a humble fishing village by the lake that, according to the Jewish-Roman historian Josephus Flavius, was transformed by local ruler Herod Philip into a polis, a Roman city. In recent years Aviam and Notley have found evidence of both periods of the settlement’s life.

“One of the goals of this dig was to check whether we have at the site a layer from the first century,” Aviam says. And they did.

The snag is that Bethsaida continued to appear in historical records – Christian and Jewish – until the late third century, then it vanished from the record for about 200 years. Research has shown that at about that time, the lake rose. Probably together with other sites around the lake, it was lost to flooding and silting.

There are around 40 centimeters (16 inches) of silt between the Roman layer and the Byzantine layer, thus the Roman city and the Jewish village lie below the silt and the fifth century church above it.

The point is that by the time Christianity took shape and by the time the lake receded, it’s possible that the local memory of where Peter and Andrew lived was gone. Come the fifth century, visiting Byzantine dignitaries could have been misled or otherwise erred in pinpointing where the apostles’ homes were when they had the basilica to be built at that spot.

The newly found inscription can’t speak to the accuracy of the choice of location, but it can lend support to the identification of el-Araj as Bethsaida and the basilica as the Church of the Apostles.

“This discovery is our strongest indicator that the basilica had a special association with St. Peter, and it was likely dedicated to him. Since Byzantine Christian tradition routinely identified Peter and Andrew’s home in Bethsaida, it seems likely that the basilica commemorates their home,” Notley says.

The mosaic thus also strengthens the case that this is the church described by the bishop of Eichstätt, Willibald, who in the eighth century made a pilgrimage to the sites where Christians believe that Jesus performed miracles around the Sea of Galilee. The bishop reported that the church was built over the house of Peter and Andrew. The Hodoeporicon – Willibald’s itinerary in the Holy Land – says he walked from Capernaum to Chorazin (Kursi) via the Church of the Apostles in Bethsaida.

“And [from Capernaum] they went to Bethsaida, from which came Peter and Andrew. There is now a church where previously was their house,” the bishop wrote.

Supporting the case of the church at el-Araj being that church, the archaeologists point out that there are no other ruined Byzantine churches on the shores of the Sea of Galilee in this area, which is now part of a nature reserve.

The inscription also supports Notley’s argument that Peter lived in Bethsaida, not Capernaum. In fact, 1,700 years of Christian tradition always placed Peter’s home in Bethsaida, he notes.

But in 1921 a theory raised by one Father Gaudence Orfali suggests Capernaum instead. There is indeed a Byzantine edifice at Capernaum too (not only at el-Araj) – an octagonal church that isn’t actually a basilica and therefore can’t have been the Church of the Apostles, Notley and Aviam contend.

So the inscription is another nail in the Orfali theory’s coffin.

The excavation is being assisted by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. “The inscription sheds light on the identification of the site with Roman and Byzantine Bethsaida, a place cursed by Jesus because the locals didn’t accept his message,” says Dr. Dror Ben-Yosef, head of heritage in the authority’s northern district, adding that inscription will be of great interest to Christian tourism.

“The dedicatory inscription with the entreaty for prayer by Simon Peter is very important for identifying the Apostle’s association with the Byzantine basilica. It confirms the testimony of the eighth century Bishop Willibald, who visited the church, that Christianity in the Byzantine period commemorated the house of St. Peter at Bethsaida and not at Capernaum,” Notley says.

“In addition, the persistent remembrance of the location of Peter’s home, in light of the recent archaeological evidence for a surrounding earlier Roman period settlement of at least 40 or 50 dunams [12 acres], adds weight to our suggestion that the site of el-Araj/Beit HaBek should be considered the leading candidate for New Testament Bethsaida.”