Archaeologists have uncovered the earliest known evidence of human migration to the Pacific, dating back over 50,000 years. This significant discovery sheds new light on one of the most arduous sea migrations undertaken by our ancestors, revealing details about how they adapted to challenging new environments.

The breakthrough came from a surprising find—a tree resin artifact—uncovered in Mololo Cave on an Indonesian island. This artifact, the earliest of its kind found outside Africa, has provided crucial insights into the timing, methods, and routes early Homo sapiens used to migrate across the Pacific.

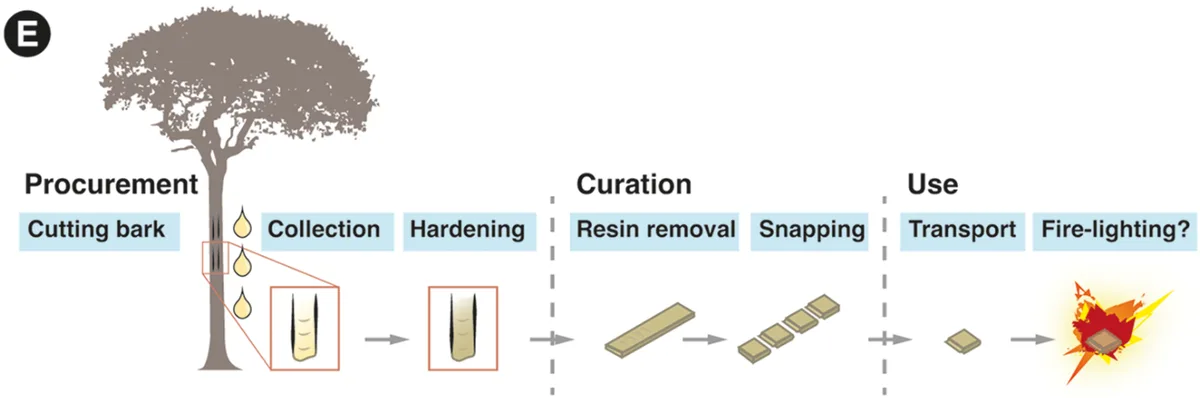

Illustration hypothesising sequence of resin artefact production (Antiquity (2024))

An international team of scientists, including researchers from New Zealand, West Papua, and Indonesia, believe the resin may have been used for a variety of purposes, including building fires, constructing boats, or making stone tools. The discovery points to the complex and resourceful strategies employed by these early humans as they navigated new and challenging environments.

Research indicates that the use of the resin involved a careful, multi-step process. The tree bark was first cut to allow the resin to drip out and harden, after which it was crafted into the desired shape. This process suggests a high level of adaptability and technological skill among early humans, essential for their survival in the rainforest regions of the Pacific islands.

The findings, published in the journal Antiquity, contribute to our growing understanding of early human seafaring. These ancient mariners made daring crossings from Asia to the Pacific Islands, eventually settling in rainforests where they adapted to a variety of environmental challenges. According to study co-authors Dylan Gaffney and Daud Aris Tanudirjo, this discovery is "an important example of human adaptation and flexibility in challenging conditions."

The exact timing and locations of these early maritime dispersals have long been unclear, although it was known that these early seafarers were the ancestors of indigenous people currently living in the Pacific islands, from West Papua to Aotearoa New Zealand. The recent excavations at Mololo Cave, located at the entrance to Mayalibit Bay in eastern Indonesia, have begun to fill in these gaps.

Within the over 100-meter-deep cave, archaeologists found layers of human occupation, along with animal bones, stone artifacts, shells, and charcoal. The animal bones suggest that the inhabitants of Mololo Cave were skilled hunters with a diverse diet that included marsupials, megabats, and ground-dwelling birds. This diversity in diet indicates that these early humans were not just maritime specialists but also adept at surviving in a variety of environments.

The deepest layers of the cave suggest that it was inhabited by early humans at least 55,000 years ago. This new evidence suggests that these prehistoric seafarers traveled along the equator to reach islands off the coast of West Papua more than 50,000 years ago. It also raises the possibility that humans settled the ancient continent of Sahul, which once connected West Papua to Australia, around 65,000 years ago.

“Seafaring simulations demonstrate that a northern equatorial route into New Guinea via the Raja Ampat Islands was a viable dispersal corridor to Sahul at this time,” the scientists wrote in their study.

Further excavations around Mololo Cave could provide even more precise information about the timing and routes of these early migrations. They may also shed light on whether these early humans played a role in the extinction of giant mammals in the region or whether these migrations involved individuals with Denisovan and Homo sapien ancestors.

This discovery marks a significant advancement in our understanding of human migration and adaptation, offering a glimpse into the resilience and ingenuity of our early ancestors as they ventured into uncharted territories.