A new study of Çatalhöyük, a prominent Neolithic settlement in Central Anatolia, sheds light on the intricate social structures, mobility patterns, and gender roles that characterized early farming societies. Occupied continuously from 7100 to 5950 BCE, Çatalhöyük is renowned for its elaborate symbolic culture, including vivid wall paintings and diverse female figurines. This research delves into the genetic, social, and cultural aspects of the Çatalhöyük community, providing a comprehensive understanding of its kinship patterns and evolving social dynamics over a millennium.

Researchers have long debated the existence of a "Mother Goddess" cult in early food-producing societies, inspired by the dominant female figurines found at various Pottery Neolithic sites across Anatolia and the Aegean. These figurines were initially interpreted as deities symbolizing fertility or as representatives of matriarchal organization. However, subsequent material culture and bioarchaeological studies have not conclusively supported the notion of dominant female roles in these societies. Genetic studies have emerged as a novel method to investigate social organization and mobility patterns in prehistoric communities, although most previous research has focused on Neolithic Europe.

In this study, a comprehensive genetic analysis was conducted using paleogenomic data from 131 individuals buried in the East and West Mounds of Çatalhöyük. These genomes were compared to those from other contemporaneous Anatolian sites to understand the genetic profile of the Çatalhöyük community and its changes over time. Additionally, the study analyzed burial practices and kinship patterns by examining the genetic relationships among individuals buried within the same buildings.

One of the central questions addressed by this research pertains to the mobility dynamics that shaped the Çatalhöyük community through the 7th millennium BCE. The genetic profile of Çatalhöyük remained relatively stable over its occupation, similar to other Pottery Neolithic sites in West and Central Anatolia. There were subtle temporal shifts in the gene pool, suggesting gene flow from neighboring regions, particularly from Central and West Anatolia. The study found no consistent affinity to populations from distant regions, such as the Levant, Zagros, or the Balkans. However, there was evidence of gene flow from genetically similar groups within the region, indicating that Çatalhöyük was not an insular community but received non-negligible levels of incomers from proximate communities.

The analysis of kinship patterns revealed that genetic kin ties were more frequently found within buildings and among neighbors during the Early period. However, this pattern weakened over time. Throughout the site's occupation, genetic connections within buildings were more often maternal than paternal. The study also identified differential funerary treatment of female subadults compared to males, with a higher frequency of grave goods associated with females. This finding suggests that key female roles persisted over time in the large Neolithic community of Çatalhöyük.

The research further explored the levels of inbreeding within the community, revealing relatively low levels of consanguinity. This suggests active inbreeding avoidance, possibly through exogamous reproductive practices or by choosing reproductive partners from outside the community. The genetic evidence indicated no practice of patrilocality in Çatalhöyük, in contrast to many Neolithic European societies, where patrilocal traditions were common.

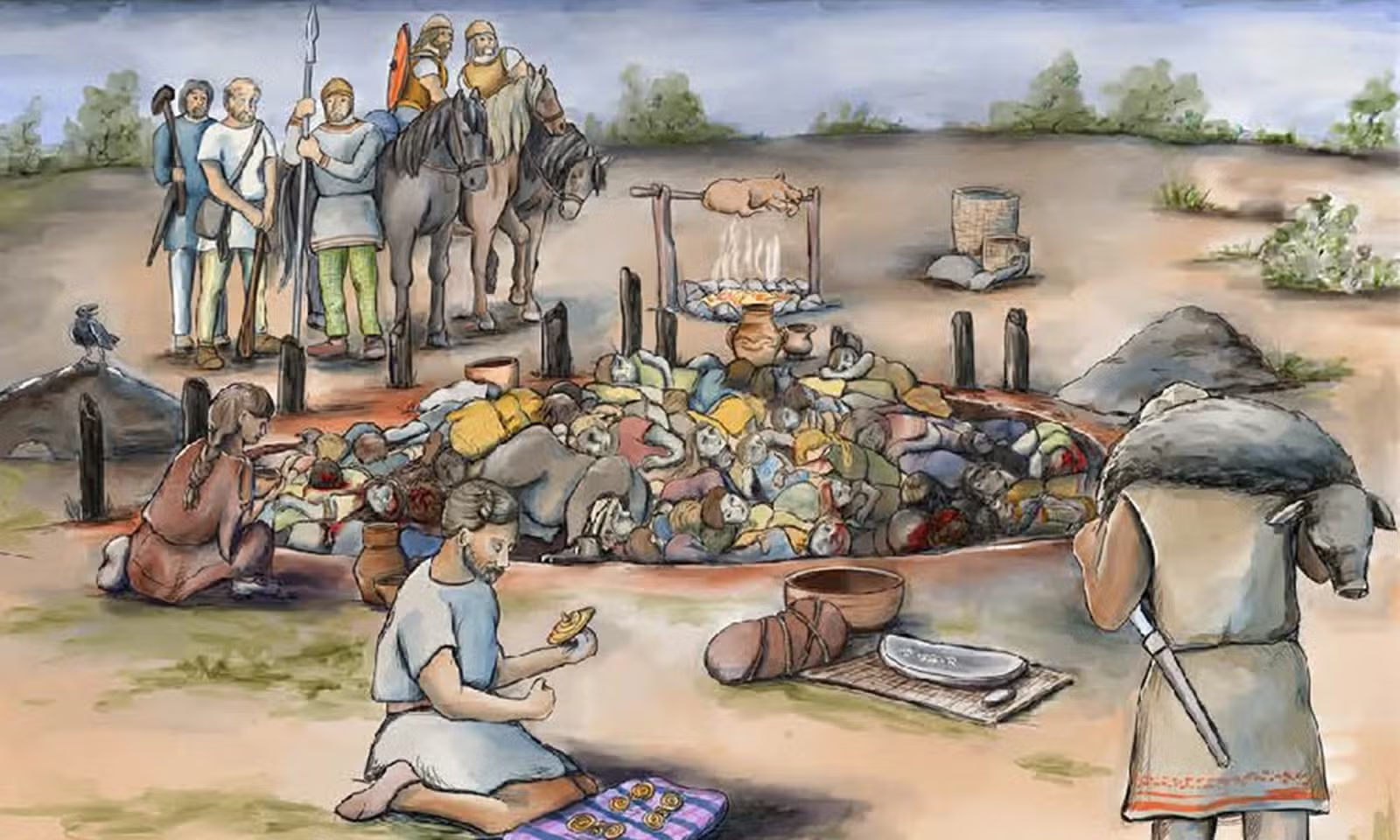

Excavations at the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Original image by Omar Hoftun.

One of the most intriguing findings of the study was the temporal change in burial practices. In the Early period, co-buried pairs within buildings were frequently close genetic kin, a pattern similar to that observed in Pre-Pottery Neolithic Anatolian settlements. However, in the Middle and Late periods, there was a significant increase in the co-burial of genetically unrelated individuals. This shift suggests changing social dynamics, possibly involving fostering or other social mechanisms that created shared environments for genetically unrelated individuals.

The research also highlighted a specific burial practice that appeared to influence body decomposition and DNA preservation. The study found that subadult burials, particularly those of female children and adolescents, had higher frequencies of grave goods compared to their male counterparts. This differentiated treatment upon death could be related to the significant role of female lineages in maintaining social continuity across generations.

The new genetic evidence from Çatalhöyük provides novel insights into the funerary practices and social organization of this major Neolithic community. It challenges previous assumptions about the dominance of patrilocality in early farming societies and highlights the unique aspects of Çatalhöyük's social structure. The findings suggest that mobility in Neolithic Anatolia might have been bilateral or matrilocal, potentially a continuation of earlier forager traditions in the region. The study also proposes that the observed changes in burial practices and kinship patterns over time might reflect the evolving social dynamics and economic independence of households within Çatalhöyük.

In conclusion, this research offers a detailed exploration of the genetic and social landscape of Neolithic Çatalhöyük. It emphasizes the persistence of maternal genetic connections and the evolving kinship practices that shaped this early farming community. The study contributes significantly to our understanding of social evolution in prehistoric societies and the complex interplay between gender, kinship, and social organization in one of the most well-documented Neolithic settlements in the world.

For a detailed examination of the study, please access the full document: Female Lineages and Changing Kinship Patterns in Neolithic Çatalhöyük.