Princeton Researchers Reveal the Complex History of Neanderthals

Since discovering the first Neanderthal bones, scientists have been curious about how these ancient humans lived and interacted with us. Questions about our differences, similarities, and interactions—whether friendly or hostile—have persisted. The discovery of Denisovans, a Neanderthal-like group in Asia and Oceania, added more intrigue.

Now, a team of geneticists and AI experts, led by Joshua Akey from Princeton, is rewriting this history. They found that modern humans and Neanderthals had a much closer and frequent contact than previously thought.

"This is the first time we've identified multiple waves of mixing between modern humans and Neanderthals," said Liming Li, who worked in Akey’s lab.

For most of history, modern humans and Neanderthals interacted. Humans split from the Neanderthal family tree about 600,000 years ago and developed our modern features about 250,000 years ago. From then until Neanderthals disappeared 30,000 years ago, they regularly met and mixed with modern humans.

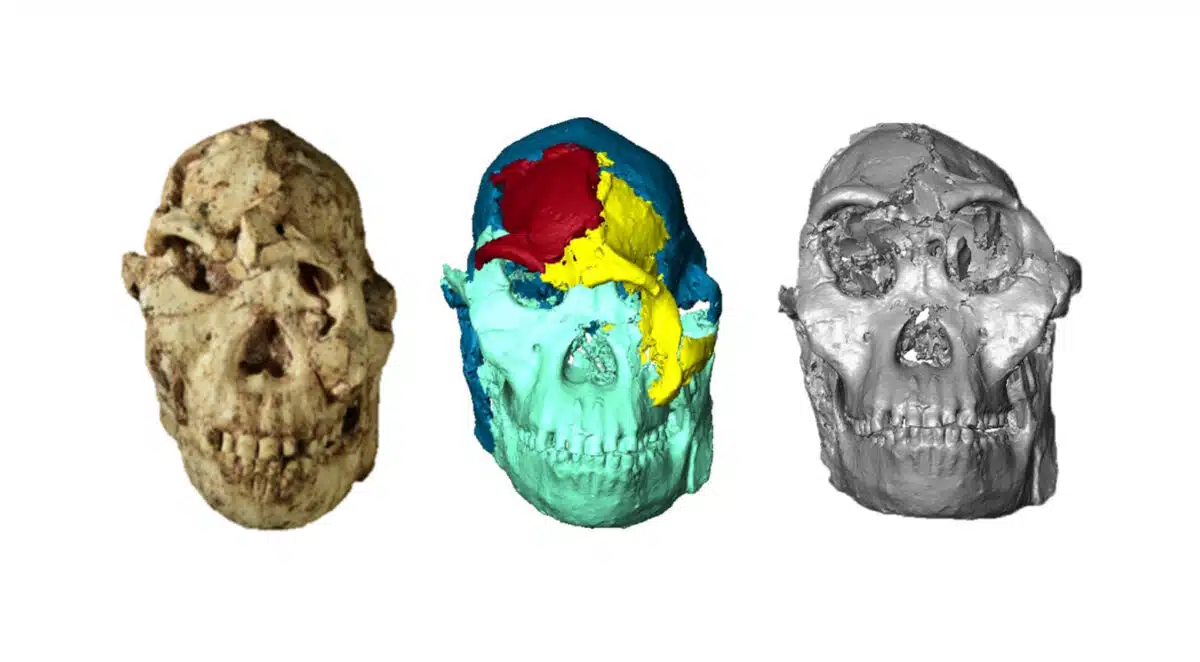

Illustration by

Matilda Luk, Office of Communications

Mapping Genetic Interactions

Using genomes from 2,000 living humans, three Neanderthals, and one Denisovan, Akey’s team mapped genetic exchanges over the past 250,000 years with a tool called IBDmix. This tool uses machine learning to decode genomes, revealing more detailed interactions than previous methods.

Their findings showed waves of contact about 200-250,000 years ago, another wave 100-120,000 years ago, and the largest wave about 50-60,000 years ago. This contrasts with the earlier belief that humans stayed in Africa for 200,000 years before spreading out.

"This shows humans were migrating out of Africa and back much earlier and more often than we thought," Akey said. This frequent movement led to many interactions with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

A New Look at Neanderthal Extinction

The study also revealed that Neanderthals had a smaller population than previously believed. Traditional genetic modeling used gene diversity as a proxy for population size. However, using IBDmix, Akey’s team showed that much of the genetic diversity in Neanderthals came from modern humans.

As a result, the estimated population of Neanderthals was reduced from 3,400 to about 2,400 breeding individuals.

Illustration by Michael Francis Reagan

How Neanderthals Disappeared

These findings suggest that Neanderthals didn't go extinct but were absorbed into human populations. Fred Smith first proposed this "assimilation model" in 1989. Akey supports this idea, saying, "Neanderthals were slowly shrinking until they merged with human communities."

"Modern humans gradually overwhelmed Neanderthals and incorporated them into our populations," Akey explained.

The research, titled “Recurrent gene flow between Neanderthals and modern humans over the past 200,000 years,” was published in the journal Science on July 13. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01GM110068 to JMA).

Read the full research here: “Recurrent gene flow between Neanderthals and modern humans over the past 200,000 years,” by Liming Li, Troy J. Comi, Rob F. Bierma, and Joshua M. Akey, appears in the July 13 issue of the journal Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1768). This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01GM110068 to JMA).