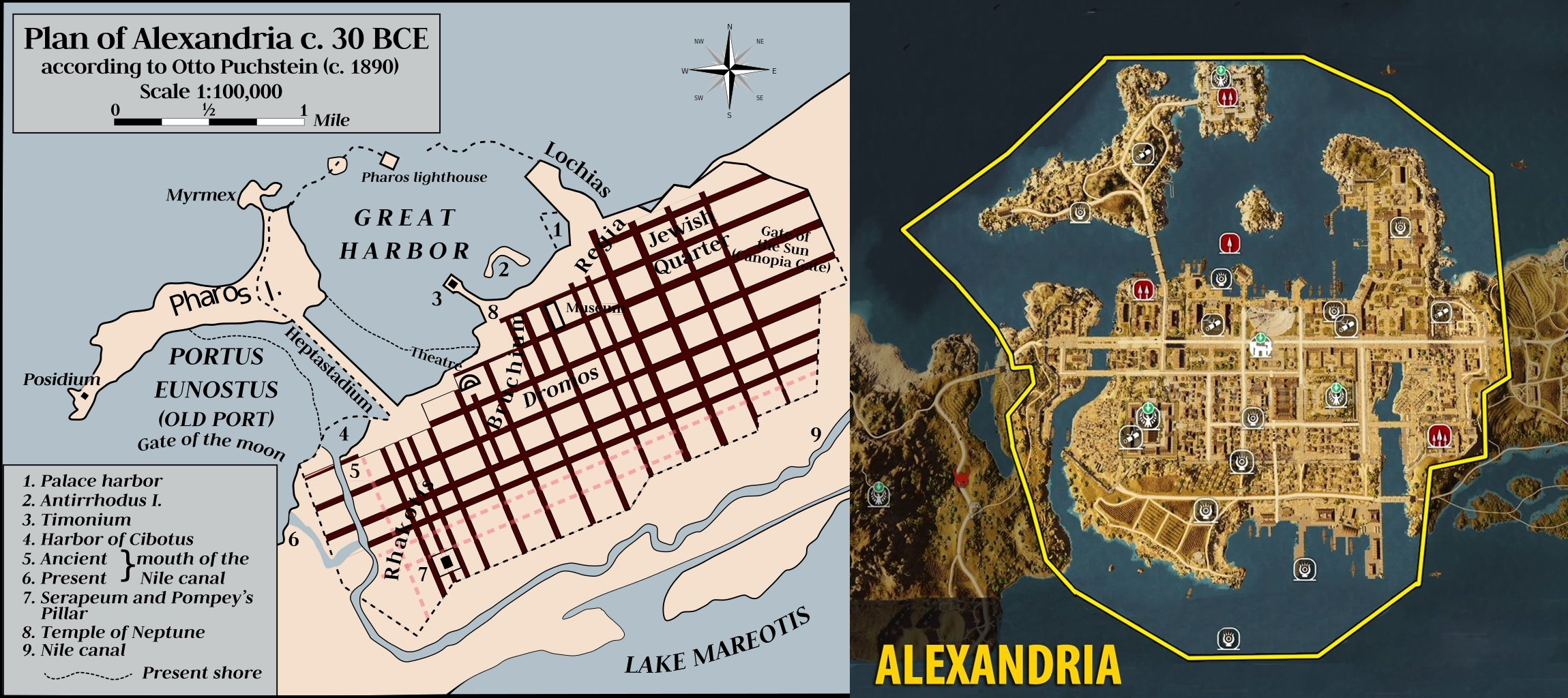

In the center of ancient, but also of modern Veria, in Macedonia, Greece, very close to the visitable archeological site of Agios Patapios, in a rescue excavation of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, in one of the few non-reconstructed plots of the city, an unexpected find came to light on Friday 17 December: a marble statue almost one meter (about 3/5 of the natural) that dates back to imperial period, when Veria, as the seat of the Macedonian Commonwealth and the official city of the imperial cult, was the first city of Macedonia, the center of political and cultural developments in the region and at the same time an axis of cohesion and a point of reference of the ancient Macedonian traditions.

With a chlamydia thrown around his left shoulder and wrapped around his arm, the naked young man with the athletic body emerges from the volume of the marble, recalling classic patterns, images of statues related to Apollo or Hermes. It is the work of a very skilled craftsman who, however, obviously never finished. For unknown reason, the sculptor, although he had advanced a lot in the elaboration of the main aspects, reaching an almost final stage, decided to abandon the effort unfinished.

This fact makes the small statue especially valuable for the study, not only of the style, but mainly of the production techniques of these works, exact copies or even more free repetitions of famous originals and helps us to approach the Veroia school of sculpture from a completely different point of view, which appears with particularly recognizable features already in the Hellenistic years and reaches its apogee at the time of the great prosperity of the city, when the Antoninians and the 'Philalexander' Severus reigned (2nd-beginning of the 3rd century AD).

The excavation on the plot continues.

The Roman imperial period is the expansion of political and cultural influence of the Roman Empire. The period begins with the reign of Augustus (r. 43 BC – AD 14), and it is taken to end variously between the late 3rd and the late 4th century, with the beginning of Late Antiquity. Despite the end of the "Roman imperial period", the Roman Empire continued to exist under the rule of the Roman emperors into Late Antiquity and beyond, except in the western empire, over which the Romans' political and military control was lost in the course of the 5th-century fall of the western Roman empire.

![screenshot-www.culture.gov.gr-2021.09.07-21_15_56https_www.culture.gov.gr_el_Information_SitePages_view.aspx_nID=3934&fbclid=IwAR36aTey5gRC9VXO4ojhQhznquFn9eI-QPFpWcs3m_OpqrTNs_V5-4a9W-0_prettyPhoto[Gallery]_3_{date}.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6047d405b02148755fb6e601/1631038628230-5R32F4XYYBNL6VL7M90M/screenshot-www.culture.gov.gr-2021.09.07-21_15_56https_www.culture.gov.gr_el_Information_SitePages_view.aspx_nID%3D3934%26fbclid%3DIwAR36aTey5gRC9VXO4ojhQhznquFn9eI-QPFpWcs3m_OpqrTNs_V5-4a9W-0_prettyPhoto%5BGallery%5D_3_%7Bdate%7D.jpg)

![A general view from the restoration of the theatre in the ancient city of Laodikea, Denizli, western Turkey [Credit: Anadolou Agency]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6047d405b02148755fb6e601/1629895858947-71NC8ITZAMIOUDUUO95P/Laodikeia-02.jpg)