When Artifacts Speak: The Veracity of Ancient Art in Archaeological Finds

The discovery of artifacts that closely resemble depictions in ancient art offers an extraordinary window into the aesthetic preferences, cultural practices, and craftsmanship of past civilizations. Through these findings, we gain invaluable insights into the daily lives of those who once wore such personal adornments and how these items were represented in their visual culture. The funerary portrait from Roman Egypt and the jewelry from Mycenaean Greece present remarkable cases where archaeological findings correlate directly with artistic representations, serving as a testament to the accuracy and value of ancient art as a historical source.

Eternal Adornment: The Intersection of Life, Death, and Jewelry

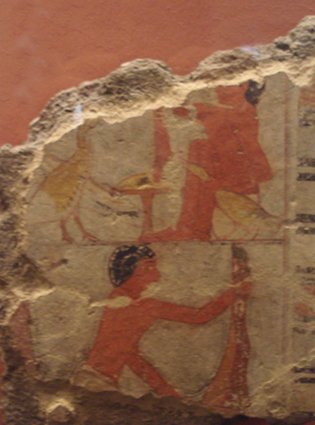

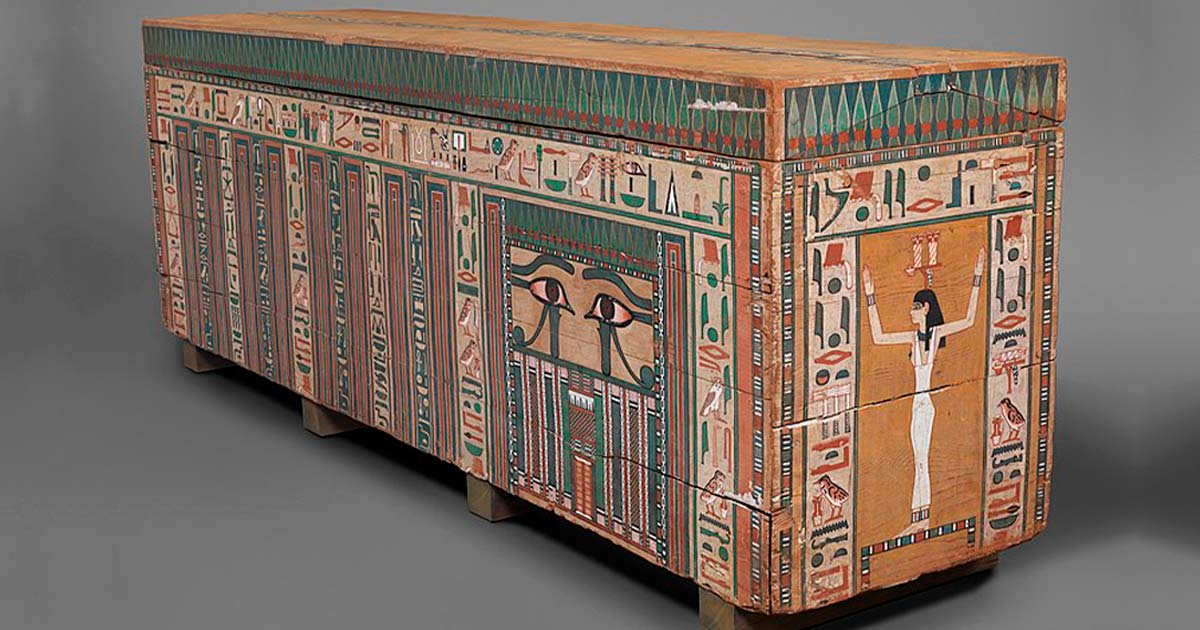

The first example features a funerary Fayum portrait of a woman from Roman Egypt, adorned with a necklace of emeralds and gold, dating back to the 2nd century AD. This era, often referred to as the period of Roman Egypt, highlights a convergence of cultural elements where traditional Egyptian practices and Roman influences coexisted and influenced one another. The encaustic painting method used to create such portraits provided a durable and lifelike representation of the deceased, making these funerary items not just art but intimate tokens of memory and identity. The fact that a real necklace mirroring the one worn in the portrait has been discovered affirms the importance placed on such objects in both life and death and suggests that the portrait likely aimed to represent the individual as she lived, with her personal belongings.

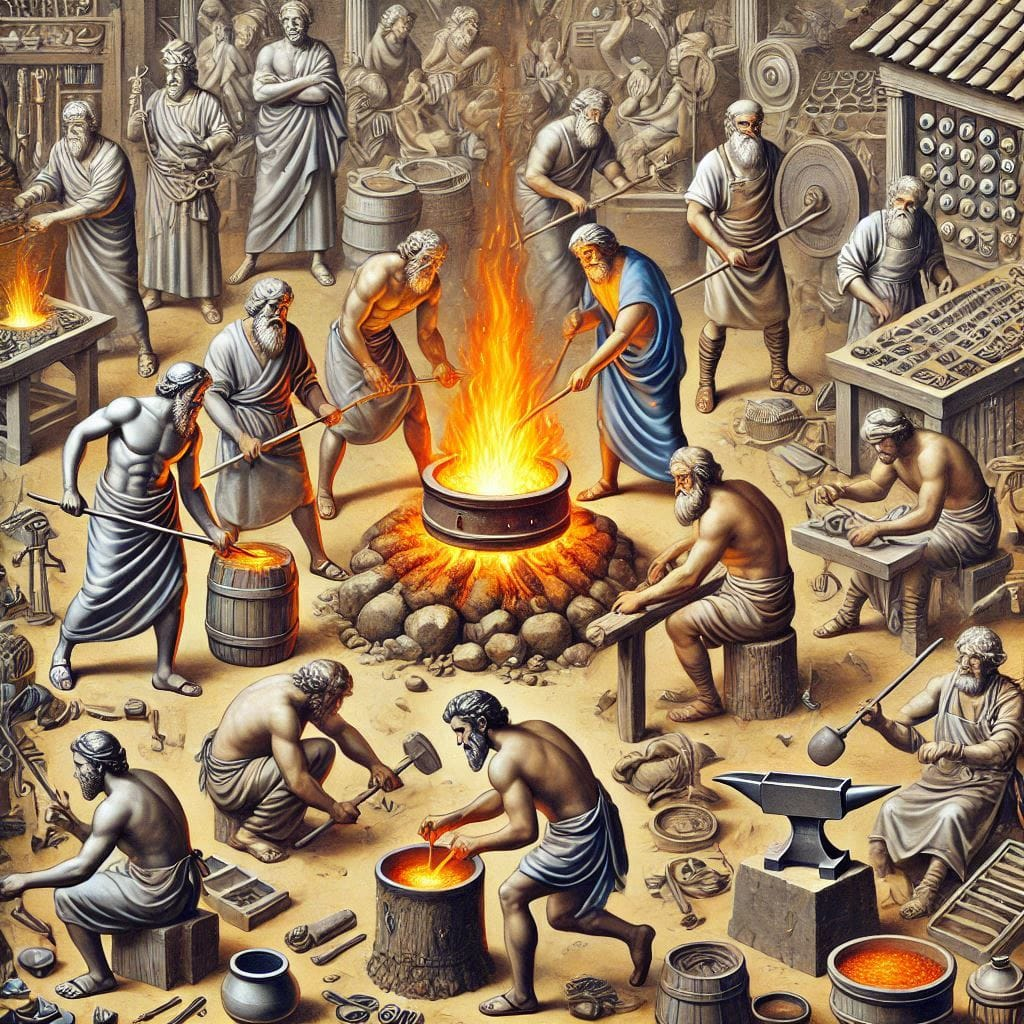

Golden Circles of Mycenae: Artistic Echoes in Aegean Goldsmithery

In the second instance, we examine a pair of gold earrings from the famed Burial Circle A of Mycenae, Tomb III, dating back to the second half of the 16th century BC. These exquisite pieces of jewelry embody the sophistication of Creto-Mycenaean goldsmithing techniques, showcasing a combination of relief work and granulation—a testament to the skill and artistry of Mycenaean craftsmen. The correlation between these earrings and those depicted on the women in the frescoes of Akrotiri on Santorini is startling. The fresco known as the "Saffron Gatherers" portrays women with similar earrings, providing not just an artistic representation of fashion of the time but an indication of trade, cultural exchange, and the flow of artistic motifs across the Aegean Sea.

Art and Archaeology in Dialogue

These correspondences between art and actual items carry profound implications. They validate ancient artworks as reliable sources for understanding the past, proving that these were not merely imaginative creations but genuine reflections of contemporary styles and customs. Moreover, they emphasize the role of personal adornments in ancient societies—not only as indicators of social status, wealth, or aesthetic preference, but also as objects of personal significance that accompanied individuals in life and, quite often, into the afterlife.

The interplay between archaeology and art history is beautifully illustrated in these examples. While archaeology provides us with the tangible remnants of the past, ancient art breathes life into these findings, allowing us to envision how these items were once used and perceived. Such discoveries underline the necessity for interdisciplinary approaches in historical inquiries, where artifacts and art coalesce to shape a fuller, more nuanced understanding of ancient peoples and their worlds. Through the careful examination of these items and their artistic counterparts, we not only reconstruct past realities but also honor the legacy of craftsmanship and expression that has endured through millennia.