In the heart of Maharashtra, India, stands a fortress unlike any other — a monolithic marvel known as Daulatabad Fort, or Devagiri ("Hill of the Gods"). This ancient citadel, carved into a single rock formation, is a testament to the architectural ingenuity and military strategy of its creators. With its imposing cliffs rising 50 meters high and a labyrinthine design, Daulatabad has captivated historians, archaeologists, and travelers for centuries. It is not merely a stronghold but a symbol of endurance and an echo of the dynasties that once ruled its walls.

The Birth of a Legendary Fortress

Daulatabad Fort's story begins in the 12th century with the Yadava dynasty, who recognized the strategic potential of this rocky hill. Devagiri was initially chosen as a capital due to its natural defenses. The steep cliffs and towering rock face provided an almost impenetrable barrier against invading forces, while the surrounding plains offered a clear view of approaching armies. This unique location enabled the Yadavas to fortify the site further, transforming it into one of the most secure fortresses in the Indian subcontinent.

The fort's construction is a marvel of medieval engineering. The builders carved the fortress directly into the rock, creating a seamless blend between natural landscape and man-made architecture. The outer walls and bastions are hewn from the living rock, making it nearly impossible for enemies to breach the defenses. The fort's design exemplifies an ingenious use of the terrain, a principle that would be adopted by later rulers who sought to fortify their own domains.

A Fortress That Changed Empires

Daulatabad's strategic importance made it a coveted prize for many rulers throughout history. In the 14th century, the fort was seized by Alauddin Khalji’s forces during the Delhi Sultanate’s expansion into the Deccan region. However, it was the decision of Muhammad bin Tughlaq that truly marked a turning point in the history of Daulatabad.

In 1327, Tughlaq famously moved his entire capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in a controversial and ill-fated attempt to consolidate power in the south. The forced migration of Delhi's population, spanning nearly 1,500 kilometers, was an ambitious and disastrous plan. Though the capital was eventually moved back to Delhi, this episode underscored the perceived invincibility of Daulatabad Fort. It was believed to be so secure that Tughlaq saw it as the ideal seat of his empire.

Unraveling the Ingenious Architecture

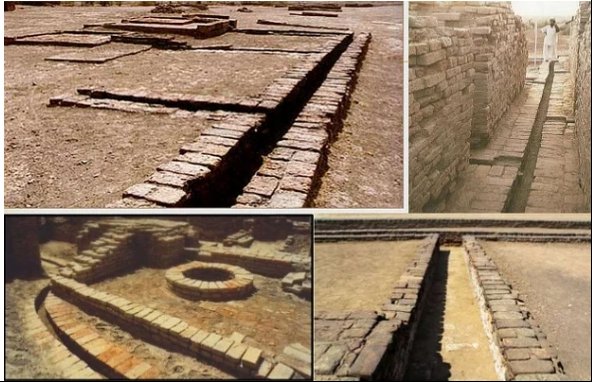

The architectural brilliance of Daulatabad Fort lies not only in its location but in its intricate defenses. The approach to the fort is designed to bewilder and exhaust attackers. The pathways wind steeply, forcing invaders into narrow, twisting passages where they are vulnerable to counterattacks. The fort features a complex series of moats, gates, and walls that create a layered defense system.

One of the most famous defensive features is the "Andheri" or dark passage, a narrow, pitch-black tunnel that winds through the rock. This passage was designed to disorient invaders and lead them into traps, such as concealed pits or dead ends. Defenders would have the advantage in these dark, confined spaces, making any assault a deadly endeavor.

Another remarkable feature is the "Chand Minar," a 30-meter tall minaret built in the 15th century by the Bahmani Sultanate, who later controlled the fort. The minaret, constructed from red stone, served as both a watchtower and a symbol of victory. It adds a striking element to the fort’s silhouette, showcasing the blend of architectural influences from different rulers over time.

The Legacy of Invincibility

Daulatabad Fort's legacy as an impenetrable stronghold is reinforced by its history of withstanding numerous sieges. During the reign of the Bahmani and later the Mughal empires, the fort saw countless attempts at conquest. Yet, it was rarely taken by force; more often, it changed hands through strategic negotiations or betrayal rather than open battle.

In the 17th century, the fort played a significant role during the Maratha-Mughal conflicts. The Maratha leader, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, made attempts to capture it but faced immense difficulty due to its formidable defenses. The fort was eventually controlled by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, who recognized its strategic importance in controlling the Deccan region.

A Timeless Monument of India’s Heritage

Today, Daulatabad Fort stands as a monument of India’s diverse and tumultuous history. The site offers visitors a glimpse into the past, where each stone and passage tells a story of ambition, warfare, and resilience. Walking through the fort, one can still sense the echo of ancient battles and the strategic minds that once shaped its defenses.

The ascent to the summit rewards visitors with breathtaking panoramic views of the surrounding countryside, a reminder of why this fortress was deemed the "Hill of the Gods." The experience is both physically demanding and spiritually uplifting, as one navigates the steep stairways and dark tunnels that have remained unchanged for centuries.

Daulatabad Fort is not just a relic of history; it is a living testament to the skill and vision of its creators. It continues to inspire awe and wonder, standing defiant against time, much like it did against the countless armies that sought to conquer it. For those seeking to explore the depths of India’s architectural and cultural heritage, a visit to Daulatabad is a journey back in time — to a place where rock, history, and legend converge.

Visiting Daulatabad: A Practical Guide

For those planning a visit, Daulatabad Fort is easily accessible from Aurangabad, Maharashtra. It is best explored in the cooler months, between October and March, when the weather is pleasant for trekking up the steep slopes. Be prepared for a challenging climb, but rest assured, the journey is well worth the effort.

In the shadow of the towering cliffs, where ancient dynasties once stood guard, one can truly appreciate the grandeur of Daulatabad Fort — a masterpiece of stone, strategy, and resilience that has stood the test of time.