The ancient Aztecs were not ignorant of the wheel, as is often claimed. In fact, they were well aware of it and used it to create wheeled animal figurines intended as toys for children. With just one more step, they could have developed the cart, all without any contact with the Old World.

The concept of the wheel is often seen as a hallmark of advanced civilization, a symbol of humanity’s progress from primitive existence to organized society. In the context of Mesoamerica, however, the wheel presents an intriguing paradox. While the ancient Aztecs and their predecessors were familiar with the wheel, they did not develop it into a form of transportation technology as seen in the Old World. Instead, they used the wheel in a very specific and limited way—primarily in the creation of wheeled animal figurines, often regarded as toys.

Discovery of Wheeled Figurines

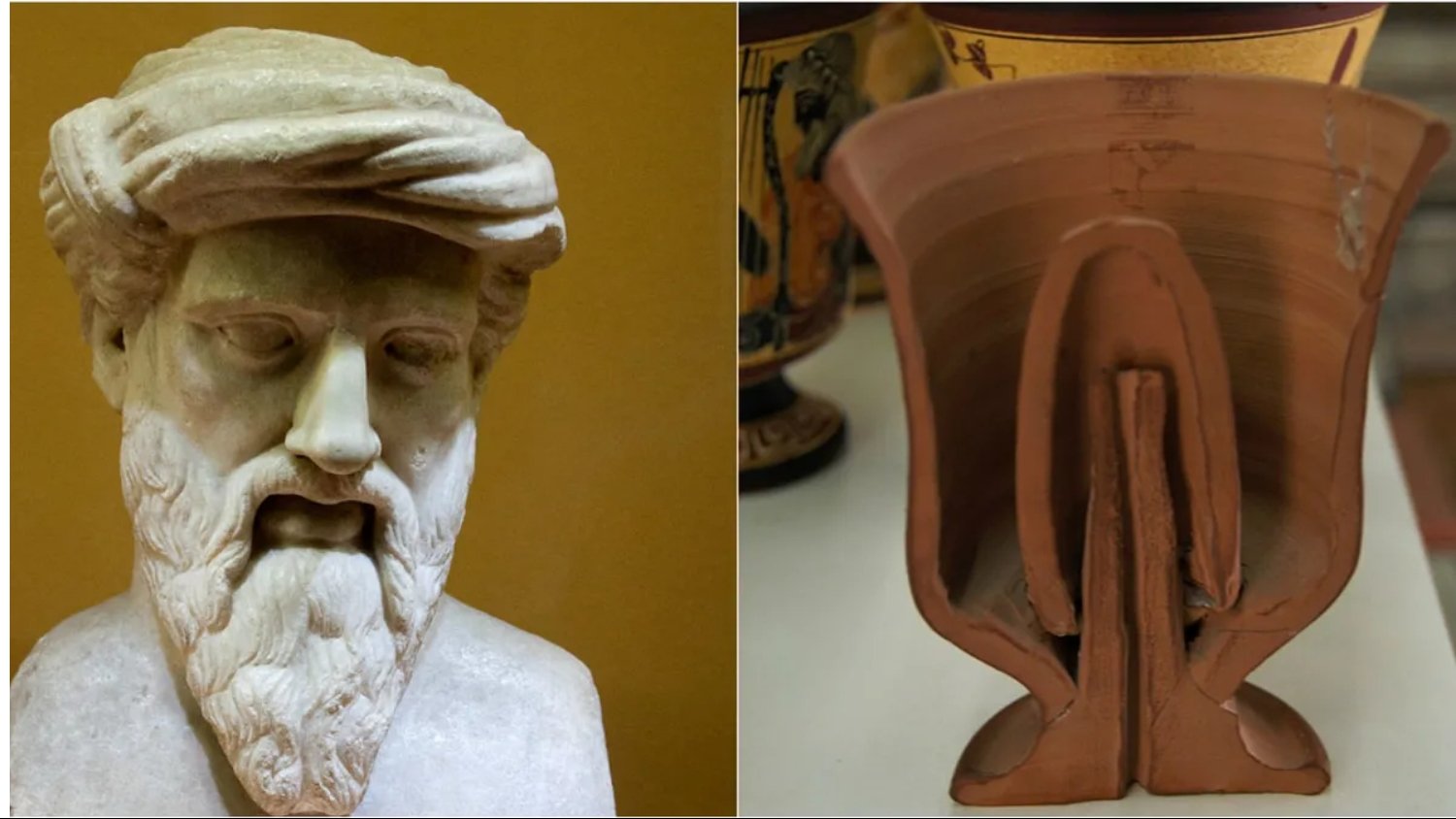

The existence of Mesoamerican wheeled toys was first brought to light in the late 19th century by the French explorer Désiré Charnay. His discovery was initially met with skepticism, but further controlled excavations at sites like Tres Zapotes in the 1940s confirmed the authenticity of these artifacts. To date, around 100 examples of these wheeled figurines have been found, primarily in regions like Veracruz, Michoacán, Guerrero, and even as far south as El Salvador. These figurines, often shaped like animals such as dogs, jaguars, monkeys, and deer, vary in construction from solid-bodied to hollow forms, with some even doubling as flutes or whistles.

Photos by Ian Mursell/Mexicolore

These artifacts, typically made by threading an axle through loops on the legs of the figurines, are robust and mobile, making them ideal for what we would consider toys. However, their purpose might have extended beyond simple toys. Given their widespread distribution and the sophistication of their construction, these wheeled figurines likely held a deeper cultural or religious significance, possibly symbolizing movement or life itself.

The Puzzle of the Wheel's Limited Use

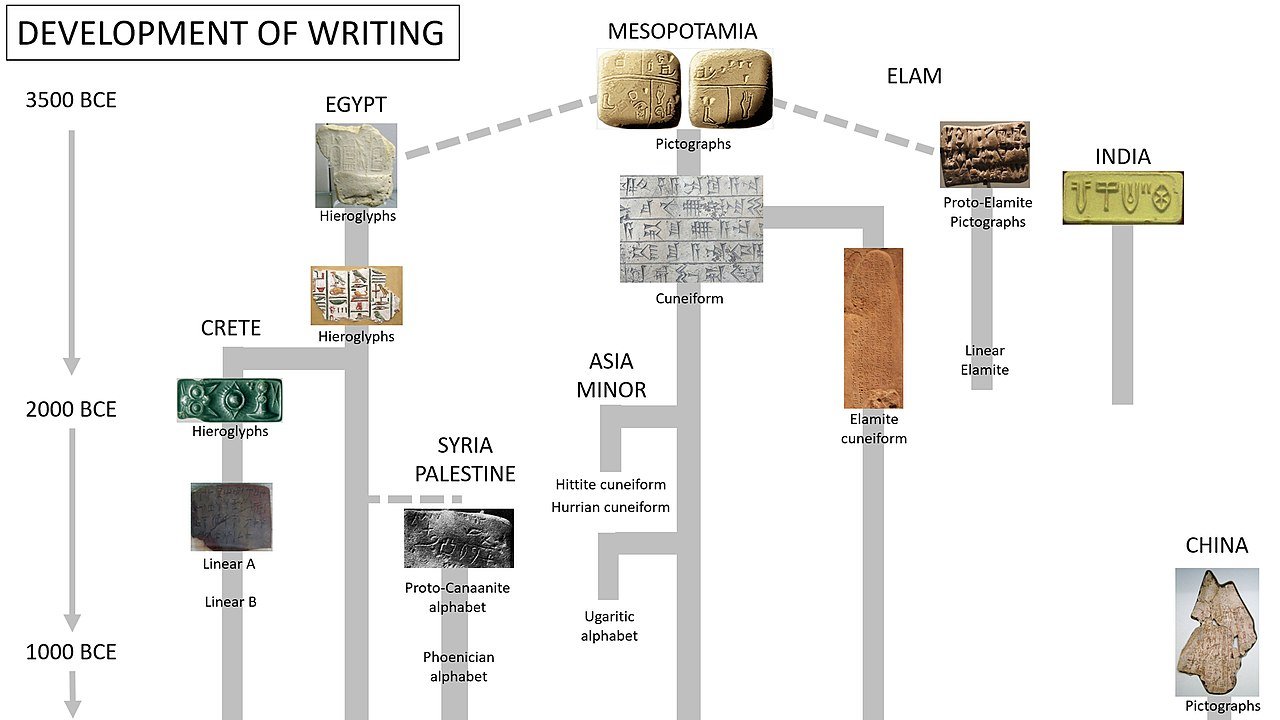

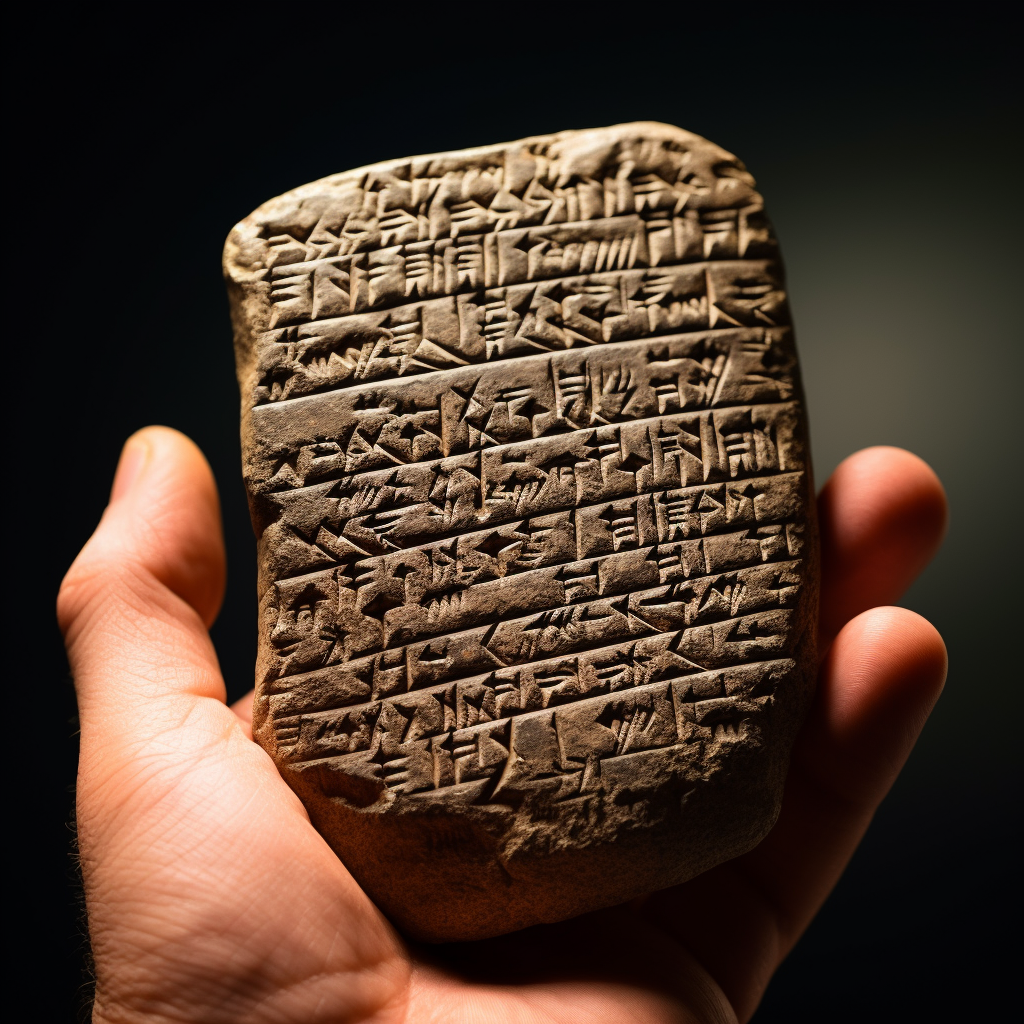

The use of the wheel in Mesoamerican culture is puzzling when compared to its role in other parts of the world. While the wheel was invented in the Old World around the 4th millennium BC and gradually spread across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, its adoption in Mesoamerica was markedly different. Despite their familiarity with the concept, Mesoamericans never applied the wheel to transportation or industrial purposes. Several theories attempt to explain this anomaly.

Firstly, the geographical and environmental conditions of Mesoamerica may have rendered the wheel impractical for transportation. The rugged terrain, dense forests, and lack of suitable draft animals (such as horses or oxen) would have made carts difficult to use. Secondly, Mexican society was deeply religious, and their beliefs could have influenced their technological choices. It is possible that the use of wheels for labor-saving purposes was seen as contrary to their spiritual values, which emphasized hard work and devotion as pathways to divine favor.

Moreover, while wheeled carts could have been useful in certain areas, such as the plains surrounding Teotihuacán, the absence of evidence for such technology suggests that cultural or religious prohibitions may have prevented their development. The effort required to move massive stones by hand, for example, might have been seen as a necessary form of sacrifice to the gods, a way of demonstrating commitment and earning spiritual rewards.

Symbolism or External Influence?

The question of why the Aztecs and their predecessors invented the wheel only to limit its use to small figurines remains open to interpretation. One theory posits that these figurines were not just toys but carried a symbolic message, perhaps reflecting a belief that the wheel was a tool meant for animals, not humans. Alternatively, some scholars suggest that the presence of the wheel in Mesoamerica might be the result of external influence, possibly from across the Pacific. The appearance of dragon-like feathered serpents and other Asian-like imagery in Mesoamerican art has led to speculation that there could have been ancient trans-oceanic contacts that introduced the concept of the wheel to the region.

However, no concrete evidence supports this theory, and it remains a topic of debate among archaeologists and historians. The idea that the wheel was considered sacred or taboo in some way also raises intriguing questions about the intersection of technology and religion in Mesoamerican culture.

The wheeled toys of the Aztecs and other Mesoamerican cultures are fascinating enigma. They demonstrate that these civilizations were aware of the wheel and its potential applications yet chose to limit its use in ways that contrast sharply with other ancient societies. Whether due to environmental, cultural, or religious reasons, the wheel in Mesoamerica serves as a reminder that technological development is not always linear or universal. It is shaped by the values, beliefs, and needs of each society, leading to unique paths of innovation and expression.