In a remarkable archaeological find, a trove of more than 100,000 ancient coins has been unearthed in Maebashi City, Japan. Discovered at the Sosha Village East 03 site during excavations initiated by the construction of a new factory, this discovery offers a unique glimpse into Japan's historical and economic connections with neighboring regions. Among the coins, some date back more than 2,000 years, with many believed to be of Chinese origin, highlighting ancient trade and cultural exchanges across East Asia.

A Treasure Trove of History

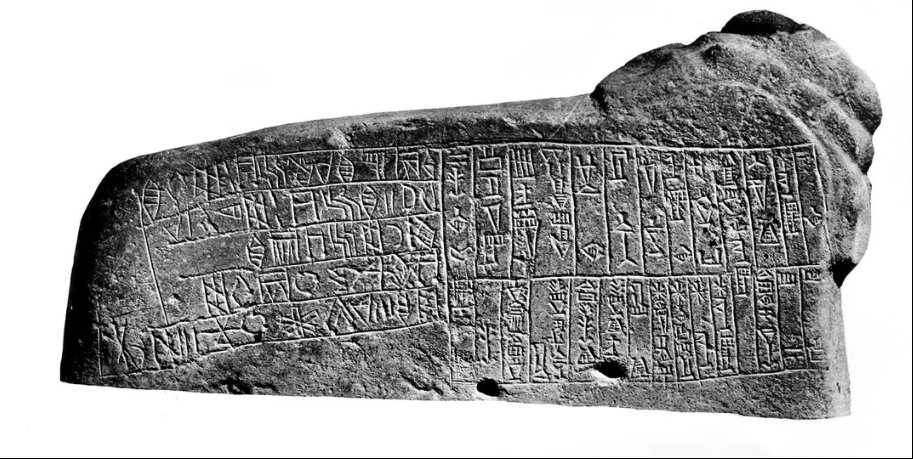

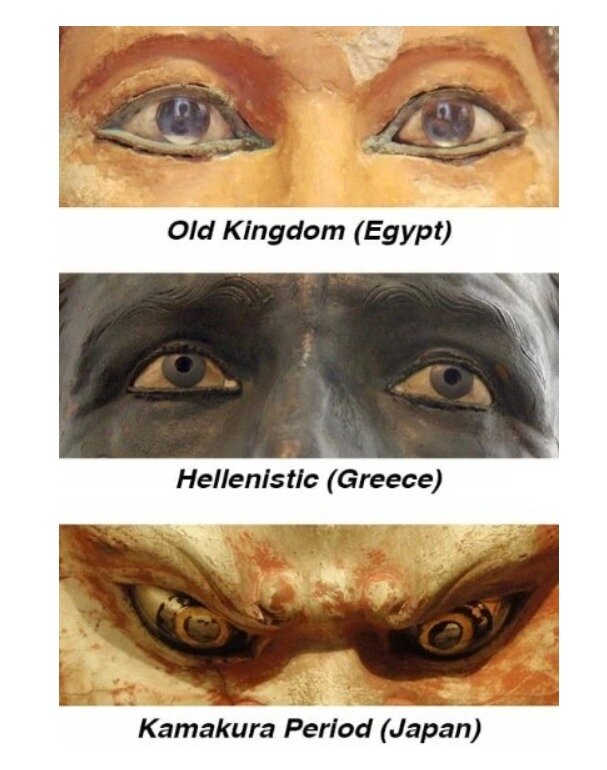

The coins uncovered include the “Ban Liang,” China’s first unified currency, minted in 175 B.C. during the Western Han Dynasty. This particular coin is significant, measuring 2.3 centimeters in diameter with a distinct 7-millimeter square hole in the center. Alongside the Ban Liang, other coins span from the seventh to the thirteenth centuries, illustrating centuries of circulation and economic activity in both China and Japan.

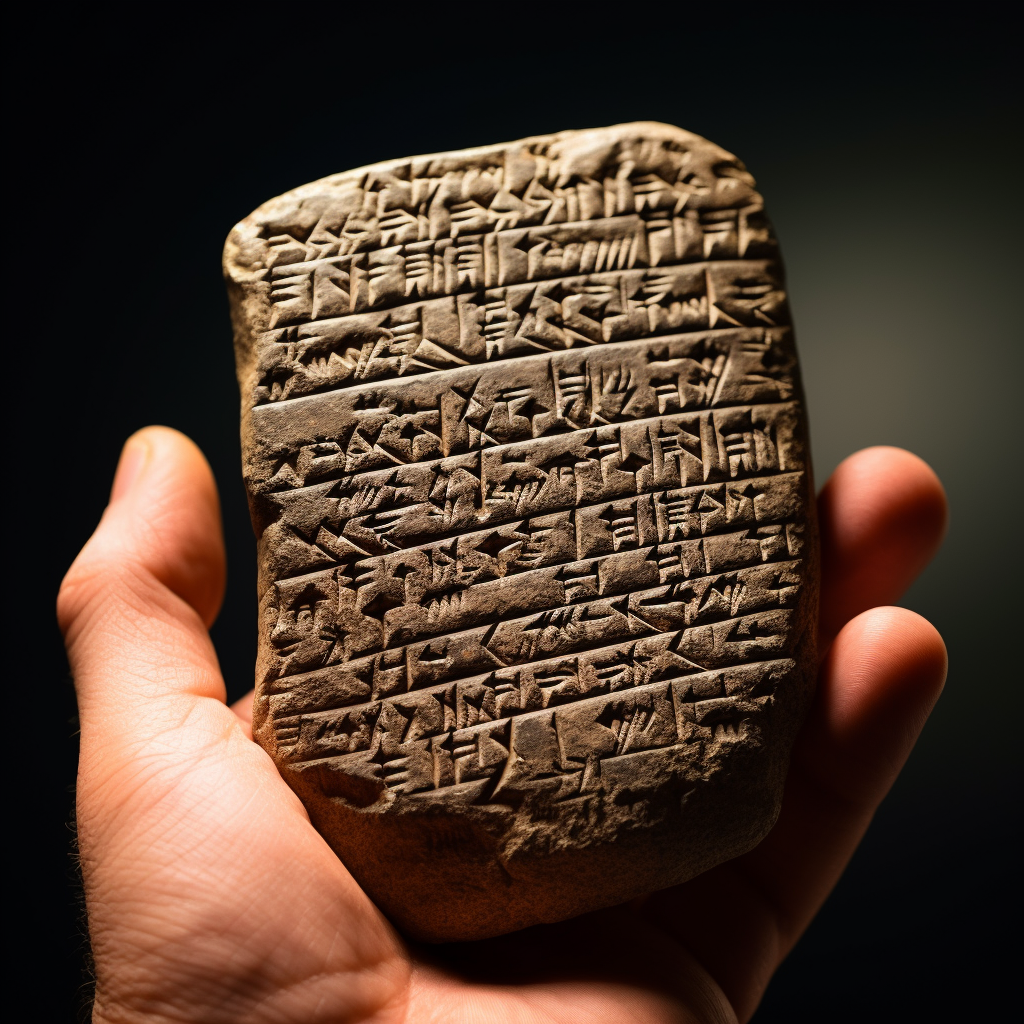

The sheer volume of the find is staggering, with the coins discovered bundled in groups of around 100, secured with straw cords known as “sashi.” Evidence suggests that some bundles consisted of 10 sashi clusters, translating to around 1,000 coins each. The discovery site, located in Gunma Prefecture, reveals layers of ancient commerce and wealth accumulation, likely tied to the region's influential residents.

The massive trove of ancient coins was dug up in Gunma Prefecture.

Historical Context

The coins were likely buried quickly as a precaution, perhaps in response to impending conflict during Japan’s medieval period. Their proximity to opulent homes suggests that local elites, wary of instability, may have hidden their wealth to protect it. The time period aligns with Japan’s Kamakura period (1185-1333), a time of political upheaval and frequent wars, reinforcing the theory that these coins were buried during a time of crisis.

Analysis of 334 coins from the cache has revealed an incredible diversity of 44 different currency types, ranging from the Western Han Dynasty in China to the Southern Song Dynasty. This wide variety of coins speaks to the extensive trade networks that existed in East Asia during this time and Japan’s interaction with the larger world.

The Role of Gunma Prefecture

The site where these coins were found holds even more significance when considering its broader historical context. It lies within a region approximately one kilometer in area that includes important sites such as the Sosha burial mounds, the San’o Temple Ruins, and the Ueno Kokubunji Temple. These ancient locations mark the region as an important cultural and political center from the late Kofun period to the Ritsuryo period, reflecting centuries of continuous activity.

Given the range of coinage and historical artifacts, archaeologists believe this area served as a bustling hub for trade and political activities. The burial of these coins could suggest that residents were preparing for potential threats to this hub, safeguarding their wealth in case of disaster.

Public Exhibition

The discovery has generated significant public interest, and the ancient coins are currently on display as part of the “Newly Excavated Cultural Artifacts Exhibition 2023” in Maebashi City’s Otemachi district. The exhibit, which runs until the 12th of this month, offers the public a rare chance to view this astounding collection of historical artifacts free of charge.

A Ban Liang coin dating from 175 B.C. Photo: Eiichi Tsunozu

The find has sparked curiosity about the nature of medieval Japan’s relationship with the rest of East Asia, as well as the local historical significance of the Gunma region. Future studies and analyses will likely provide further insights into the economic and cultural exchanges of the time and how these coins came to be buried in this location.

This discovery underscores the richness of Japan’s archaeological landscape, revealing layers of history that connect the country not just to its own past, but to a broader narrative of global commerce and interaction across centuries.

A New Chapter in Archaeological Research

While the preliminary results offer a wealth of information, further research will continue to refine our understanding of this extraordinary find. As scholars examine the coins more closely, they hope to pinpoint the exact circumstances under which they were buried and better understand the economic dynamics of the region during the medieval period.

The Sosha Village East 03 site is poised to become a key focus for archaeologists studying the intersection of Japanese and East Asian history, offering new perspectives on the flow of goods, currency, and cultural practices in ancient times. The ongoing study of these ancient coins promises to shed light on a complex and interwoven historical period, demonstrating the importance of archaeology in uncovering the many layers of our shared past.

Maebashi City Government

Cover Photo: Maebashi City Government