The "Red Basilica" (Turkish: Kızıl Avlu), also called variously the Red Hall and Red Courtyard, is a monumental ruined temple in the ancient city of Pergamon, now Bergama, in western Turkey. The temple was built during the Roman Empire, probably in the time of Hadrian and possibly on his orders. It is one of the largest Roman structures still surviving in the ancient Greek world. The temple is thought to have been used for the worship of Egyptian gods – specifically Isis and/or Serapis, and possibly also Osiris, Harpocrates and other lesser gods, who may have been worshipped in a pair of drum-shaped rotundas, both of which are virtually intact, alongside the main temple.

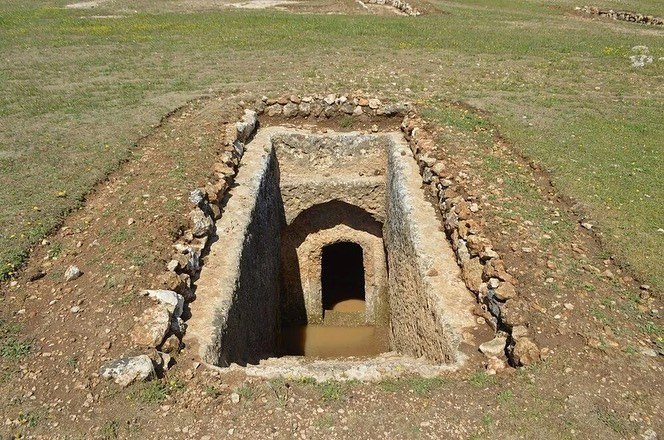

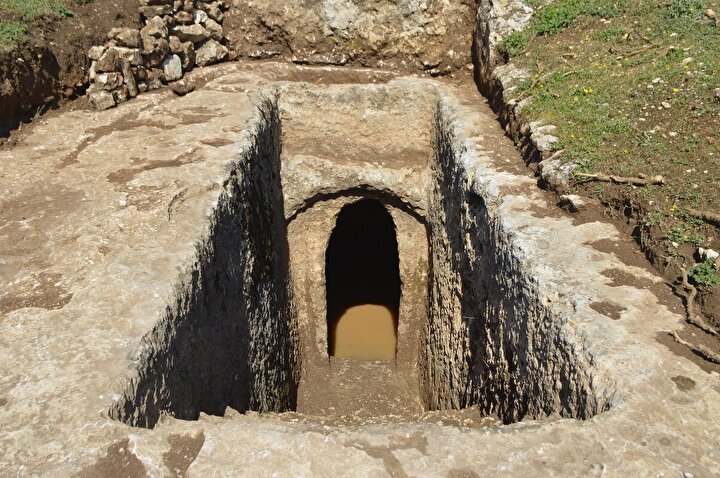

Although the building itself is of an immense size, it was only one part of a much larger sacred complex, surrounded by high walls, that dwarfed even the colossal Temple of Jupiter in Baalbek. The entire complex was built directly over the River Selinus in a remarkable feat of engineering that involved the construction of an immense bridge 196 metres (643 ft) wide to channel the river through two channels under the temple. The Pergamon Bridge still stands today, supporting modern buildings and even vehicle traffic. A series of tunnels and chambers lies under the main temple, connecting it with the side rotundas and giving private access to different areas of the complex. Various drains, water channels and basins are located in, around and under the main temple and may have been used for symbolic reenactments of the flooding of the Nile.

The temple was converted by the Romans into a Christian church dedicated to St John but was subsequently destroyed. Today the ruins of the main temple and one of the side rotundas can be visited, while the other side rotunda is still in use as a small mosque.

West view of the Red Basilica

History

The temple's date of construction is not recorded, but from the style of the sculptures and the building techniques a date in the first half of the second century AD has been proposed. Its use of red brick on a massive scale, unique in Asia Minor but relatively common in Italy at the time, indicates that the architect was not local. The immense size and lavish construction of the complex points to an extremely wealthy patron who sent a Roman architect and brick masons to Pergamon to build the temple. The most likely candidate is the emperor Hadrian himself. He is known to have been an enthusiastic sponsor of the Egyptian gods; he built temples of Isis and Serapis at various places in the Roman world, including at his own villa in Tivoli.

At some point during the Christian era the temple was gutted by fire. It was not restored, but was redeveloped in the 5th century AD as a Christian basilica, built inside the shell of the destroyed temple. Arcades were built dividing the interior into a central nave and two side aisles. The eastern wall was demolished and replaced with an apse. The floor level was raised by about 2 metres (6.6 ft), obscuring the original Roman floor, though the former floor level has since been restored by archaeologists. The church was probably destroyed by the forces of the Arab general Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik, who besieged and looted the city in 716–717 during his unsuccessful bid to conquer Constantinople. Pergamon fell into Turkish hands in 1336 and the building was converted into a mosque.

Interior of the temple, showing the podium and (left) the base of the cult statue. Smaller statues of the gods would have stood in the side alcoves.

The complex has been investigated and excavated in a series of campaigns by the German Archaeological Institute. In 1906–1909 P. Schazmann prepared detailed drawings of the ruins during a German excavation of the Hellenistic city. The temple and temenos were excavated by Theodor Wiegand from 1927. New archaeological studies were carried out from 2002 to 2005 under A. Hoffmann. Restoration efforts have also been pursued, first in the 1930s under O. Bayatlı, the Director of the Bergama Museum, and later in the 1950s and 1960s. Further restoration work was conducted on the main temple in 2006 and the south rotunda was restored between 2006 and 2009.

Description

The temple was built in the lower city of Pergamon at the foot of the hill on which the ancient city's acropolis stood. It was located at the eastern end of what was originally an immense sacred precinct or temenos, 270 m long by 100 m wide (890 ft × 330 ft), which was surrounded by stone walls standing at least 13 metres (43 ft) high. Most of the temenos was destroyed and built over long ago, but substantial fragments of the walls remain standing to a height of 13 m today. The main entrance lay on the western side of the temenos through a colossal marble gateway; smaller gateways were located on the same side, north and south of the main gate. From there, visitors walked some 200 metres (660 ft) to an immense propylon (or monumental gateway) in front of the temple, supported by a row of columns standing 14 metres (46 ft) high.

The temenos was built on top of the River Selinus, presumably because the person who commissioned the complex wished it to be located in the city centre rather than in an outlying district. As the city was already substantially built up, the river bed offered an otherwise unused location for the temple complex and reduced the number of properties that would have to be demolished to make way for it. The river was channelled into two tunnels passing diagonally for a distance of about 150 metres (490 ft), northwest to southeast, under the temenos and temple. This structure, the Pergamon Bridge, still stands today and continues to drain the river underneath the complex.

Photo from the end of 19th century

Use and purpose

The temple was certainly used to worship Egyptian gods, as the presence of Egyptianised atlantids indicates. Which specific gods were worshipped there is, however, unclear. An inscription referring to the temple mentions "Serapis, Isis, Harpocrates, Osiris, Apis, Helios on a horse ... Ares and the Dioskouroi". Another inscription mentions Serapis, and a small terracotta head of Isis was discovered in the area of the temenos. One of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri from Egypt refers to Isis as ὲν Περγάμῳ δεσπότις ('she who rules in Pergamon'). The temple may well have been dedicated to Isis, though some historians have interpreted it as a Serapeum (temple of Serapis) instead. The two rotundas may have been used for the worship of Horus and Anubis.

The layout of the temple provides more clues about how it was used. Unlike Greek temples, where the entire building was considered to be the house of the divinity, the god worshipped in the "Red Basilica" was confined to the eastern half of the temple. Similar layouts are found in other Isis and Serapis temples elsewhere in Asia Minor and Greece. The temenos is a vastly enlarged equivalent of enclosures found elsewhere in Greek mystery sanctuaries, such as the one as Eleusis in Greece where the Eleusinian Mysteries were performed annually. The purpose of its high walls was to prevent outsiders from witnessing ceremonies held within the temenos and temple precinct, thus preserving the mystery of the rituals.

The ancient cult complex in an 18th century gravure

Water appears to have been a central theme of the ceremonies held at the temple, judging from the number of water features (basins, troughs and so on) in the complex. The basins outside the temple may have been purely decorative but those inside seem to have been intended for use in ceremonies. These may have included purification rituals – sprinkling the faithful with water – and possibly also a ritual re-enactment of the flooding of the Nile. Robert A. Wild suggests that the deep basin dividing the temple into its eastern and western halves may have been designed to convey flood- or rainwater into the temple during peak rainfall periods in the winter. The basin also served to separate the public western half of the temple from the sacred eastern half. Initiates may have been taken through the underground passages to the cultic area, where they would be presented to the worshippers filling the western end of the temple. Something of this nature is hinted at by Apuleius in Metamorphoses: "There in the middle of this sacred temple before the image of the goddess I was made to stand on a wooden pulpit."