Follow the history of the Egyptian Language in this video created by Costas Melas, from the 4rth millennium until today. Archaic Egyptian, Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, Demotic, Coptic, Writing Systea, Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, Demotic and Coptic.

A policeman stands guard near the step pyramid of Djoser in Egypt's Saqqara necropolis, south of the capital Cairo, on March 5, 2020.

Mohamed El-Shahed / AFP / Getty

Djoser Pyramid Re-Opens to Public After 14 Years of Renovation Work

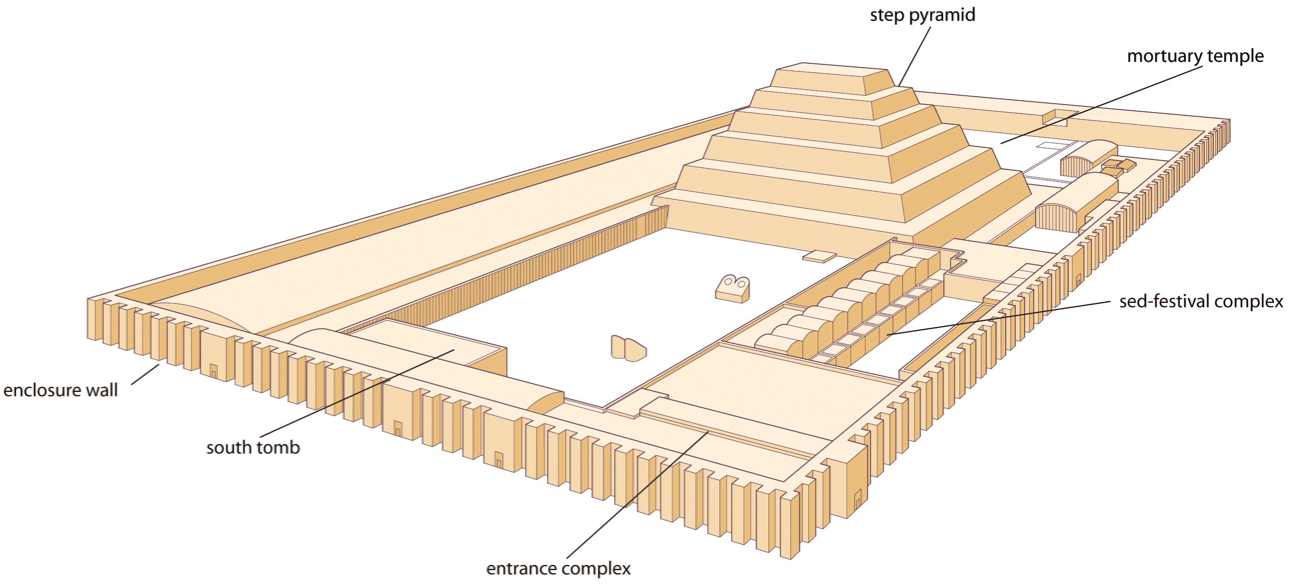

According to the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Egypt’s first pyramid and the first stone pyramid in the world – belonging to the dynasty 3 king Djoser – has reopened to the public following 14 years of renovation work.

People enter the Pyramid of Djoser in Saqqara outside Cairo.

Oliver Weiken/Picture Alliance / Getty

The opening of the pyramid, a beloved and popular tourist site around 35 km from Cairo, was attended by Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly and Khaled El Enany, Minister of Tourism and Antiquities.

Djoser pyramid’s renovation work cost around US$ 6.6 million (almost 103 million EGP) but many experts and Egyptologists agree that it was much needed as the structure had been deteriorating over the years, namely its facades, due to the harsh climate.

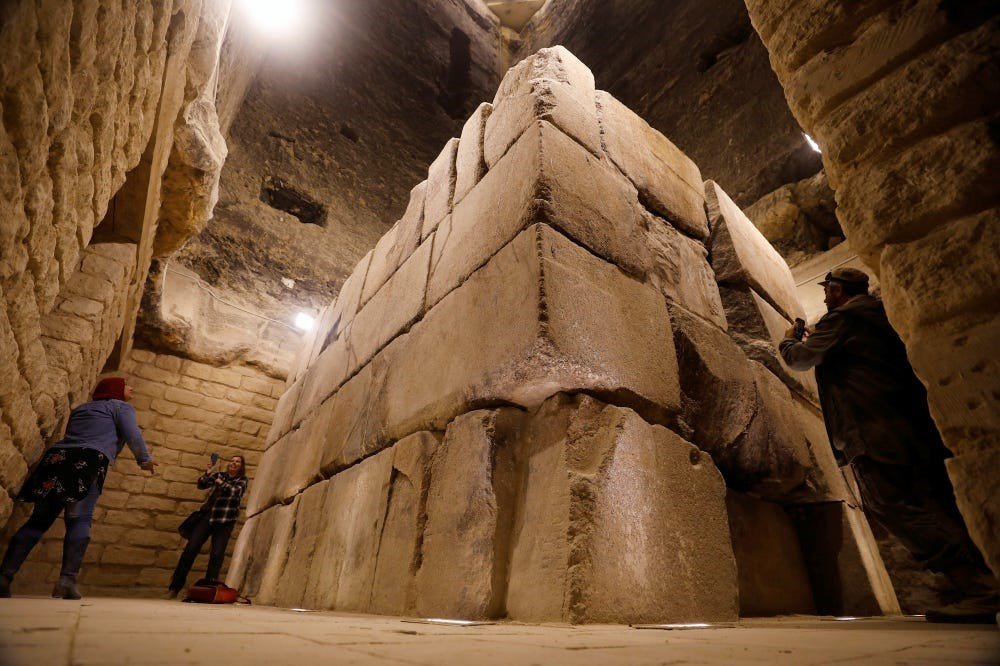

Tourists take pictures at the burial chamber and sarcophagus of King Djoser inside the standing step pyramid of Saqqara, south of Cairo, Egypt March 5, 2020.

Mohamed Abd El Ghany / Reuters

However, it was the pyramid’s interior which was considered in the worst state, having born the brunt of the destructive 1992 earthquake in Egypt.

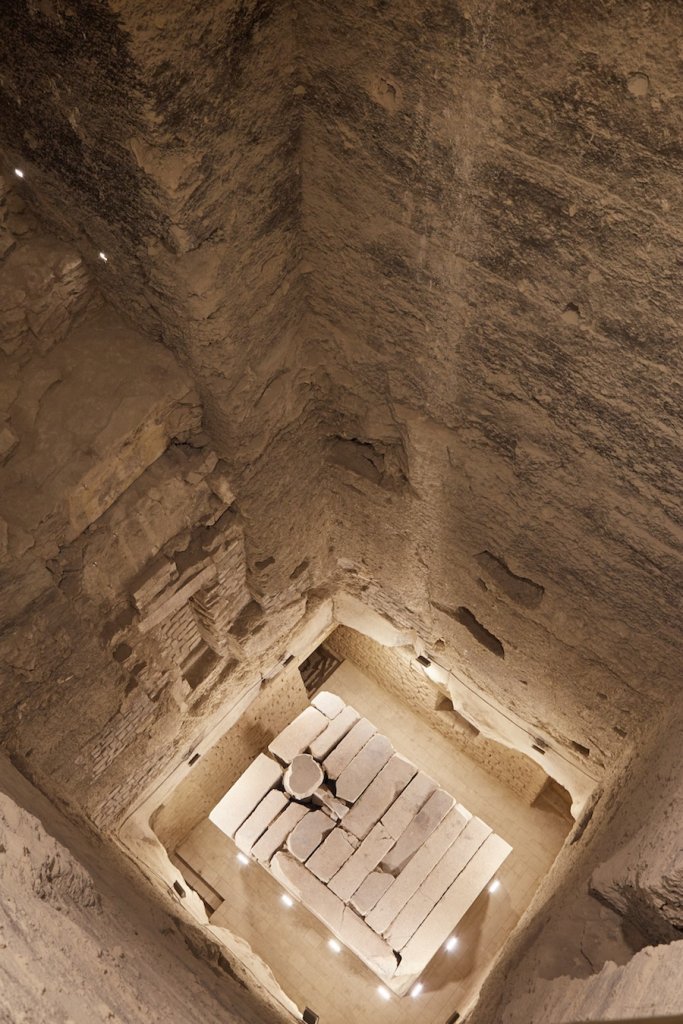

Accordingly, the restoration work oversaw internal and external restoration, with special focus given to clearing the pathway inside the 4,600-year-old pyramid as well as restoring the stone sarcophagus in which the ancient ruler would have been buried in.

Top view of the burial chamber and sarcophagus of King Djoser inside the standing step pyramid of Saqqara, south of Cairo, Egypt March 5, 2020.

Mohamed Abd El Ghany / Reuters

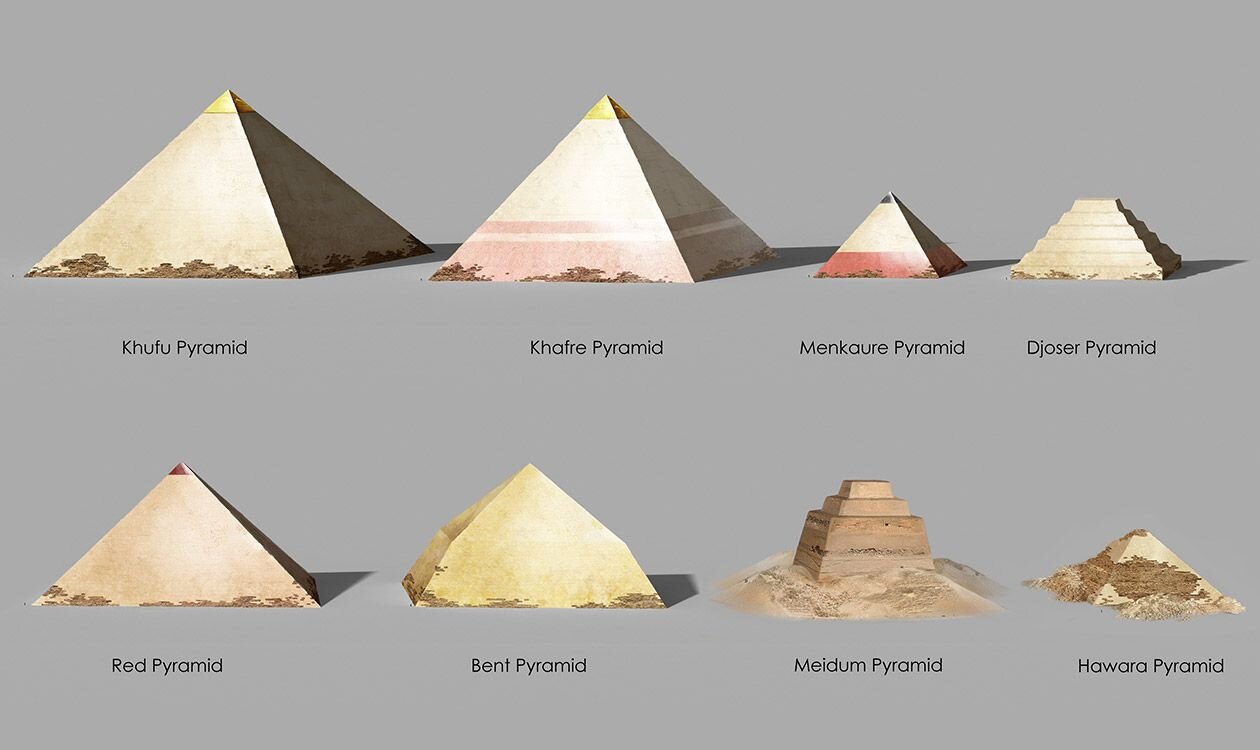

Prior to the pyramid of Djoser, Egyptian rulers were interred in above ground funerary structures which were usually rectangular; they were called ‘mastabas’ and they were located above the burial pit. Thus, this structure, often likened to a ‘stairway of to heaven’, is considered an architectural innovation and stepping stone which eventually lead to the creation of the ‘true’ triangular pyramids which can be witnessed in Saqqara and at the Giza plateau.

Currently, the pyramid can be visited with prices set at 100 EGP (US$ 6.39) for foreigners and 50 (US$ 3.20) for foreign students. For Egyptians and Arab tourists, the tickets are 40 EGP (US$ 2.56) and 20 (US$ 1.28) for students.

The monument, which was designed by famed and deified architect Imhotep in ancient Egypt, is registered in the UNESCO World Heritage list since 1979.

The Scientific Explanation of the 'Pharaoh's Curse'

100-year-old folklore and pop culture have perpetuated the myth that opening a mummy's tomb leads to certain death.

Movie mummies are known for two things: fabulous riches and a nasty curse that brings treasure hunters to a bad end. But Hollywood didn't invent the curse concept.

The "mummy's curse" first enjoyed worldwide acclaim after the 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, Egypt.

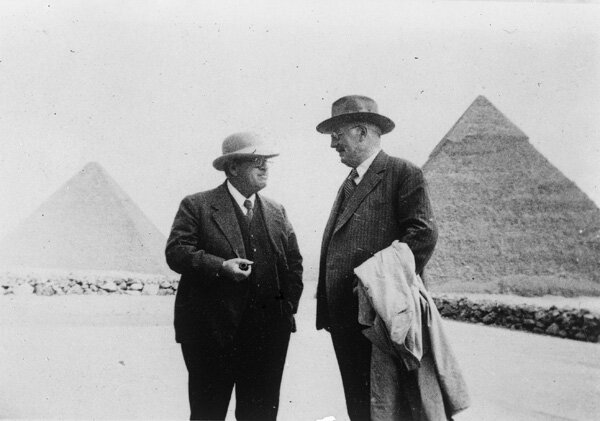

When Howard Carter opened a small hole to peer inside the tomb at treasures hidden for 3,000 years, he also unleashed a global passion for ancient Egypt.

Tut's glittering treasures made great headlines—especially following the opening of the burial chamber on February 16, 1923—and so did sensationalistic accounts of the subsequent death of expedition sponsor Lord Carnarvon.

In reality, Carnarvon died of blood poisoning, and only six of the 26 people present when the tomb was opened died within a decade. Carter, surely any curse's prime target, lived until 1939, almost 20 years after the tomb's opening.

But while the pharaoh's curse may lack bite, it hasn't lost the ability to fascinate audiences—which may be how it originated in the first place.

Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon at the door of the burial chamber. Photo by Harry Burton (1879-1940)

Birth of the Curse

The late Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat conducted a comprehensive search and concluded that the concept began with a strange "striptease" in 19th-century London.

"My work shows quite clearly that the mummy's curse concept predates Carnarvon's Tutankhamen discovery and his death by a hundred years," Montserrat told the Independent (U.K.) in an interview some years before his own death.

Montserrat believed that a lively stage show in which real Egyptian mummies were unwrapped inspired first one writer, and subsequently several others, to pen tales of mummy revenge.

The thread was even picked up by Little Women author Louisa May Alcott in her nearly unknown volume Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy's Curse.

"My research has not only confirmed that there is, of course, no ancient Egyptian origin of the mummy's curse concept, but, more importantly, it also reveals that it didn't originate in the 1923 press publicity about the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb either," Montserrat stressed to the Independent.

But Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist at the American University in Cairo and a National Geographic Society grantee, believes the curse concept did exist in ancient Egypt as part of a primitive security system.

She notes that some mastaba (early non-pyramid tomb) walls in Giza and Saqqara were actually inscribed with "curses" meant to terrify those who would desecrate or rob the royal resting place.

"They tend to threaten desecrators with divine retribution by the council of the gods," Ikram said. "Or a death by crocodiles, or lions, or scorpions, or snakes."

Tomb Toxin Threat?

In recent years, some have suggested that the pharaoh's curse was biological in nature.

Could sealed tombs house pathogens that can be dangerous or even deadly to those who open them after thousands of years—especially people like Lord Carnarvon with weakened immune systems?

The mausoleums house not only the dead bodies of humans and animals but foods to provision them for the afterlife.

Lab studies have shown some ancient mummies carried mold, including Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus flavus, which can cause congestion or bleeding in the lungs. Lung-assaulting bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus may also grow on tomb walls.

These substances may make tombs sound dangerous, but scientists seem to agree that they are not.

F. DeWolfe Miller, professor of epidemiology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, concurs with Howard Carter's original opinion: Given the local conditions, Lord Carnarvon was probably safer inside Tut's tomb than outside.

"Upper Egypt in the 1920s was hardly what you'd call sanitary," Miller said. "The idea that an underground tomb, after 3,000 years, would have some kind of bizarre microorganism in it that's going to kill somebody six weeks later and make it look exactly like [blood poisoning] is very hard to believe."

In fact, Miller said, he knows of no archaeologist—or a single tourist, for that matter—who has experienced any afflictions caused by tomb toxins.

But like the movie mummies who invoke the malediction, the legend of the mummy's curse seems destined never to die.

BY BRIAN HANDWERK, National Geographic

New Scans of the Great Pyramid Confirm Major Discovery Inside

New scans revealed unprecedented details about the internal structure of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The so-called Big Void inside the Pyramid is now measured at 40 meters in length. Its contents remain a profound mystery.

Two years ago, a group of scientists from around the world used revolutionary technology to study the Great Pyramid of Giza in unprecedented detail. Experts were hoping to discover new details that may lead to our better understanding of how the pyramid was built and its purpose. The group of scientists scanned the pyramid looking for previously unknown chambers.

Although we have still not discovered what tools and technologies its ancient builders used, we have found that the pyramid is far more mysterious than we’ve ever imagined, hidden within its chambers and rooms that we thought never existed.

Two years a paper published in Nature announced that a massive void was discovered within the Great Pyramid of Giza, just above the famous Grand Gallery. Measuring at least 30 meters / 100ft. in length, this discovery constituted the first major discovery made at the Great Pyramid of Giza since the 19th century.

The Scan Pyramid project began in October of 2015. The project has seen experts from France, Japan, and Egypt participate in one of the largest studies of the pyramid ever attempted.

ScanPyramids, as the project is called, is a cross-disciplinary multinational archeological mission that uses state-of-the-art, non-destructive methods to scan various monuments for hidden cavities, chambers, or structures. This is achieved by using infra-red thermography and muons tomography.

Muon tomography essentially uses cosmic ray muons to produce three-dimensional images of volumes using information stored in the Coulomb scattering of the muons. Muons can penetrate much more deeply than x-rays, reason why experts use muon tomography to image through much thicker material than x-ray based tomography.

In other words, muon radiography will help detect differences in density inside the Pyramid providing experts with an internal image of the ancient monument.

Scan Pyramids: Confirming a major discovery

Two years after the historic discovery made by ScanPyramids, researchers have now revealed a new video announcing that the large void within the Great Pyramid of Giza has been confirmed by a series of new scans taken from different points inside the pyramid, including scans made from the so-called relieving chambers that are located just above the so-called King’s Chamber.

Three different methods of muography were used, each independent of the other, and each was corroborated by in-depth computer simulations.

First, Nagoya University used plates containing a chemical film sensitive to muons. Another Japanese team from the KEK Institute transported and reassembled a very sophisticated device–piece by piece–inside the Queen’s Chamber; it was an electronic instrument that uses different technologies to detect the muons.

The third group of researchers from France installed equipment outside of the pyramid. They installed “telescopes” fitted with gas detectors and pointed them towards the pyramid.

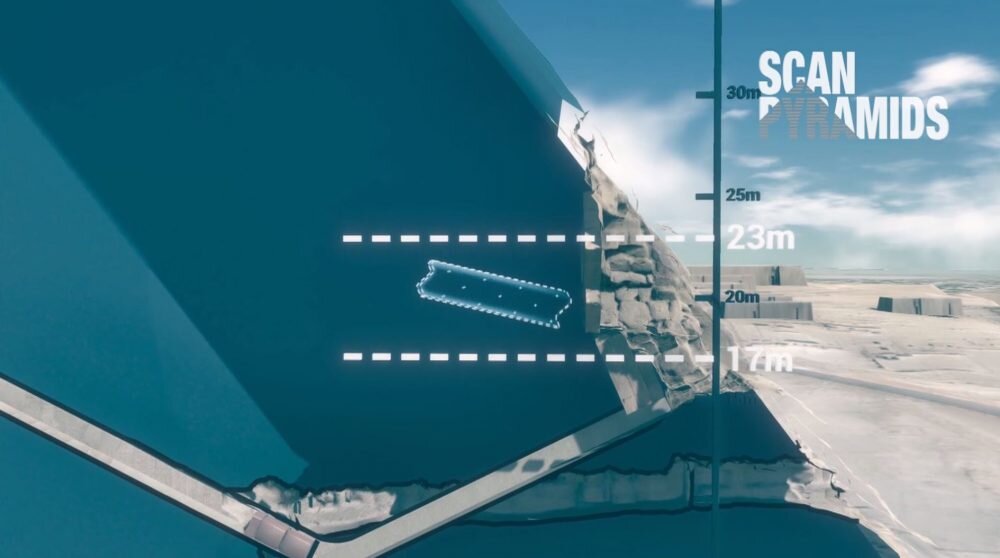

In 2016, the devices from the ScanPyramids project revealed the existence of a cavity situated behind the chevrons of the north face, but without being able to determine its exact architectural shape.

A screengrab of the confirmed discovery of the Great Pyramid’s corridor. Image Credit: HIP Institute/ ScanPyramids / Vimeo.

In 2017, 2018, and 2019, new plates were placed on the descending corridors and the niches of the so-called Al-Mamun tunnel. All of the scans reconfirmed the existence of the cavity, located between 17 and 23 meters above ground level. This corridor is at least 5 meters long. It is horizontal and probably slopes upwards. Where it leads remains a mystery.

However, experts were able to rule out the theory of the corridor leading down, parallel to the descending corridor.

The new video also offers fresh data confirming the results first published in 2017. Perhaps the greatest discovery was the existence of the so-called void.

The Mysterious void is located just above the Grand Gallery, no more than 15 meters above it. Its minimum length has been reestimated thanks to the new scans to 40 meters in one single section. Its slope, however, remains debatable.

The new scans saw experts install new devices inside the Grand Gallery to observe the “Big Void” from several angles. Nagoya University placed several devices along the Grand Gallery. Other devices were installed in the King’s Chamber and the relieving chambers above it.

A cross-section of the Great Pyramid of Giza showing the location of the Big Void. Image Credit: HIP Institute/ ScanPyramids / Vimeo.

Unsurprisingly, the Big Void was again observed from these new measuring points, confirming and refining the results published in 2017.

The devices placed above the King’s Chamber inside the Pyramid revealed new clues about the structure. The researchers have revealed that their latest scans revealed no anomalies present between the arches, the relieving chamber, and the pyramid’s summit.

In 2018, the ScanPyramids scientists moved their devices into the unfinished underground chamber of the Great Pyramid to understand the parts of the pyramid located above the underground chamber. This new muon data capture is ongoing, and experts hope to reveal new clues about the pyramid.

The ScanPyramid project will continue, and new data will most likely be revealed later in 2021.

By Ivan Petrievic, Curiosmos

The 'Boundary Stelae of Akhenaten': Meaning of Pharaoh's Texts and his Message for the 'Cult of Aten'

The 'Boundary Stelae of Akhenaten' that oversees his city, ancient Amarna: What is the meaning of Pharaoh's Texts and What kind of message did he left for the 'Cult of Aten'?

The Boundary Stelae of Akhenaten are a group of royal monuments in Upper Egypt. They are carved into the cliffs surrounding the area of Akhetaten, or the Horizon of Aten, which demarcates the limits of the site. The Pharaoh Akhenaten commissioned the construction of Akhetaten in year five of his reign during the New Kingdom. It served as a sacred space for the god Aten in an uninhabited location roughly halfway between Memphis and Thebes at today's Tell El-Amarna. The boundary stelae include the foundation decree of Akhetaten along with later additions to the text, which delineate the boundaries and describe the purpose of the site and its founding by the Pharaoh. Total of sixteen stelae have been discovered around the area. According to Barry Kemp, the Pharaoh Akhenaten did not “conceive of Akhetaten as a city, but as a tract of sacred land”.

Purpose of the Stelae

Sixteen boundary stelae have so far been discovered at Tell El-Amarna. The boundary stelae of Akhenaten were carved in locations around the city of Akhetaten that was built by the pharaoh Akhenaten to his god Aten. Their purpose is to demarcate the boundaries of the holy site of Aten, but also to inform people about the intentions of the pharaoh and the nature of the site as a holy place for Aten. The boundary stelae are a major source of information about the religious reforms of Akhenaten, as they include the full titulary of the god Aten and other clues about the cult practiced in Akhetaten. The stelae are royal monuments commissioned by the pharaoh and thus contain an inherent bias that favors the king's undertakings and condemns those who opposed his reforms. They are nonetheless important historical artefacts and are very useful to historians.

Reconstruction of the original appearance of Boundary Stela N, AMARNA PROJECT

Earlier Proclamation

Stelae K, M, and X on the east side of the Nile contain what Davies termed the Earlier Proclamation. All three stelae contain both vertical and horizontal lines of text. Stela K is the best preserved and was made to replace Stela M which was damaged early on, thus necessitating a replacement. Both Stela K and Stela M are located in the southern side of the site and the text in their horizontal lines reads from left to right, away from the center of the site. Stela X is located in the northern side of the site and it is a mirror image of stelae K and M in that its horizontal lines read from right to left, also away from the center. The inscription on the stelae K, M, and X is dated to the fifth regnal year of Akhenaten in day 13 of the season of Peret. They include the full title of the god Aten, as well as titles of the king Akhenaten and the king's wife Nefertiti. The stelae also describe the founding of the site by the pharaoh, reasons for choosing it, the proposed layout of the site, instructions regarding the burials of the royal family and certain notables, and instructions for the maintenance of the cult of Aten. The Earlier Proclamation also includes a promise from Akhenaten to build various temples and other structures to the god Aten in the location. The latter part of the text is fragmentary and has inspired a variety of interpretations.

Later Proclamation

What Davies termed the Later Proclamation was carved on stelae J, N, P, Q, R, S, U, and V on the eastern side of the Nile, and on stelae A, B, and F on the western side. The inscription of the Later Proclamation is dated to year six of Akhenaten's reign in the day 13 of the season of Peret, which corresponds with the one year anniversary of the Earlier Proclamation, and includes a “renewal of the oath” that appeared in the Earlier Proclamation regarding the location and permanence of the site. with some modifications to include more land, especially a swath of agricultural land in the cultivation on the western side of the river. Titulary of the god Aten is also given, along with a repetition of much of the Earlier Proclamation. The Later Proclamation includes a description of events that took place after the inscription of the Earlier Proclamation, such as a journey of the pharaoh to the southeastern crag of the site. The Later Proclamation also mentions six principal boundary stelae that delimit the site.

Map of Boundary Stelae, AMARNA PROJECT

Repetition of the Oath and the Colophon

Early in the year eight of Akhenaten's reign, in the season of Peret, a repetition of the oath of Akhenaten regarding the site is added to the stelae furnished with the Later Proclamation, and later that same year, in the season of Akhet, another text, termed the “Colophon” by Davies, is added to stelae A and B. The Colophon contains a reaffirmation of the borders and Aten's ownership of the site.

Translation of the 1st Proclamation:

‘On this day, when One (Pharaoh Akhenaten) was in Akhetaten, His Majesty [appeared] on the great chariot of electrum... Setting [off] on a good road [toward] Akhetaten, His place of creation, which He made for Himself that He might set within it every day... There was presented a great offering to the Father, The Aten, consisting of bread, beer, long- and short-horned cattle, calves, fowl, wine, fruits, incense, all kinds of fresh green plants, and everything good, in front of the mountain of Akhetaten...’

The king addresses his gathered courtiers:

‘As the Aten is beheld, the Aten desires that there be made for him [...] as a monument with an eternal and everlasting name. Now, it is the Aten, my father, who advised me concerning it, [namely] Akhetaten. No official has ever advised me concerning it, not any of the people who are in the entire land has ever advised me concerning it, to suggest making Akhetaten in this distant place. It was the Aten, my fath[er, who advised me] concerning it, so that it might be made for Him as Akhetaten... Behold, it is Pharaoh who has discovered it: not being the property of a god, not being the property of a goddess, not being the property of a ruler, not being the property of a female ruler, not being the property of any people to lay claim to it....’

‘I shall make Akhetaten for the Aten, my father, in this place. I shall not make Akhetaten for him to the south of it, to the north of it, to the west of it, to the east of it. I shall not expand beyond the southern stela of Akhetaten toward the south, nor shall I expand beyond the northern stela of Akhetaten toward the north, in order to make Akhetaten for him there. Nor shall I make (it) for him on the western side of Akhetaten, but I shall make Akhetaten for the Aten, my father, on the east of Akhetaten, the place which He Himself made to be enclosed for Him by the mountain...’

‘I shall make the “House of the Aten” for the Aten, my father, in Akhetaten in this place. I shall make the “Mansion of the Aten” for the Aten, my father, in Akhetaten in this place. I shall make the Sun Temple of the [Great King's] Wife [Nefernefruaten-Nefertiti] for the Aten, my father, in Akhetaten in this place. I shall make the “House of Rejoicing” for the Aten, my father, in the “Island of the Aten, Distinguished in Jubilees” in Akhetaten in this place... I shall make for myself the apartments of Pharaoh, I shall make the apartments of the Great King's Wife in Akhetaten in this place.’

‘Let a tomb be made for me in the eastern mountain of Akhetaten. Let my burial be made in it, in the millions of jubilees which the Aten, my father, has decreed for me. Let the burial of the Great King's Wife, Nefertiti, be made in it, in the millions of yea[rs which the Aten, my father, decreed for her. Let the burial of] the King's Daughter, Meritaten, [be made] in it, in these millions of years. If I die in any town downstream, to the south, to the west, to the east in these millions of years, let me be brought back, that I may be buried in Akhetaten. If the Great King's Wife, Nefertiti, dies in any town downstream, to the south, to the west, to the east in these millions of years, let her be brought back, that she may be buried in Akhetaten. If the King's Daughter, Meritaten, dies in any town downstream, to the south, to the west, to the east in the millions of years, let her be brought back, that she may be buried in Akhetaten. Let a cemetery for the Mnevis Bull [be made] in the eastern mountain of Akhetaten, that he may be buried in it. Let the tombs of the Chief of Seers, of the God's Fathers of the [Aten.......] be made in the eastern mountain of Akhetaten, that they may be buried in it. Let [the tombs] of the priests of the [Aten] be [made in the eastern mountain of Akhetaten] that they may b[e bur]ied in it’.

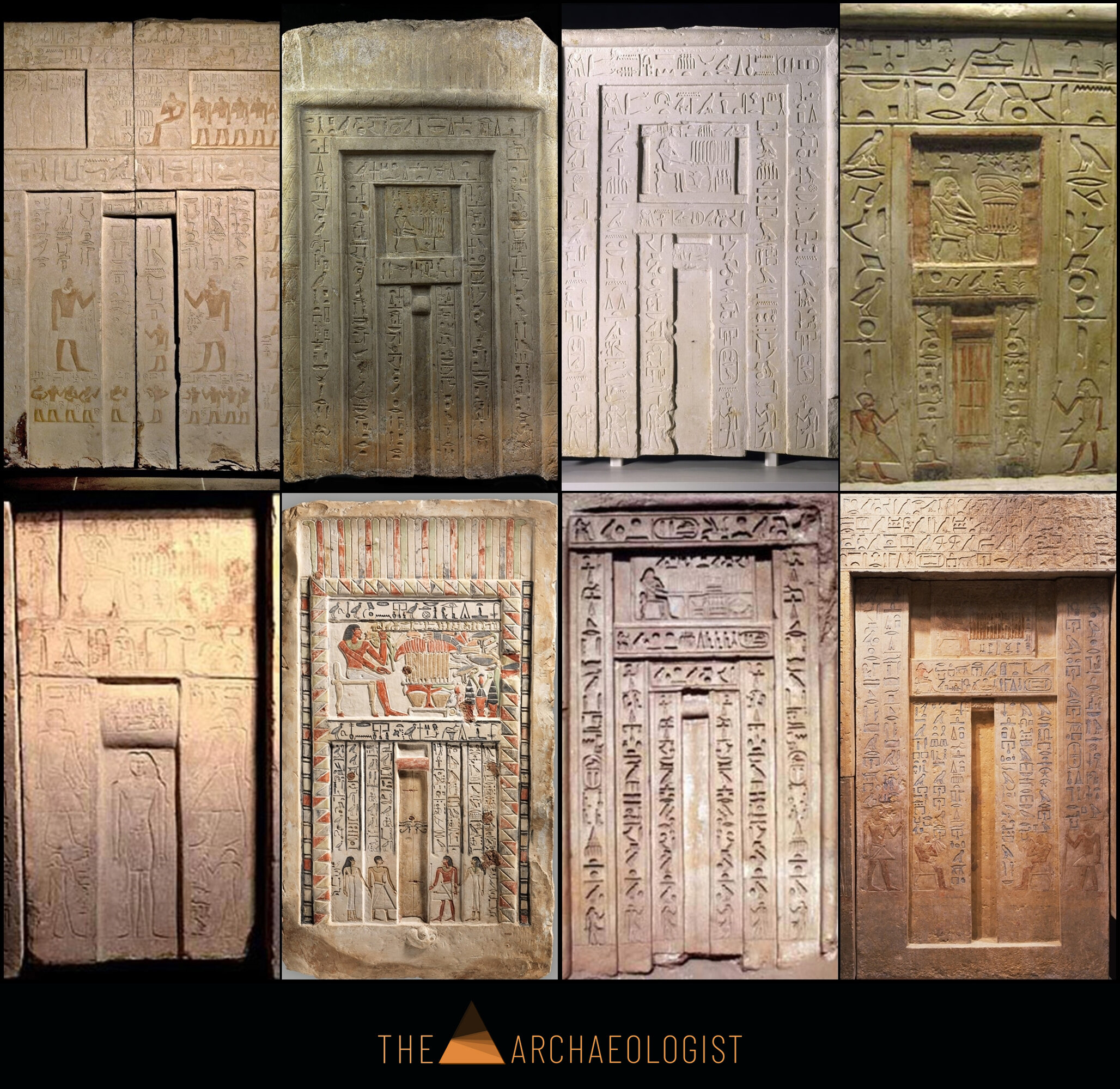

The 'False Doors' of the Egyptian Tombs: A Threshold between the Worlds of the Living and the Dead

A false door, or recessed niche, is an artistic representation of a door which does not function like a real door. They can be carved in a wall or painted on it. They are a common architectural element in the tombs of ancient Egypt, but appeared possibly earlier in some Pre-Nuragic Sardinian tombs. Later they also occur in Etruscan tombs and in the time of ancient Rome they were used in the interiors of both houses and tombs.

Mesopotamian origin

Egyptian architecture was influenced by Mesopotamian precedents, as it adopted elements of Mesopotamian Temple and civic architecture. These exchanges were part of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations since the 4th millennium BC.

Naked devotee offering libations to a temple of Inanna, c. 2500 BCE. Ur, Mesopotamia.

Recessed niches were characteristic of Mesopotamian Temple architecture, and were adopted in Egyptian architecture, especially for the design of false doors in Mastaba tombs, during the First Dynasty and the Second Dynasty, from the time of the Naqada III period (circa 3000 BC). It is unknown if the transfer of this design was the result of Mesopotamian workmen in Egypt, or if temple designs appearing on imported Mesopotamian seals may have been a sufficient source of inspiration for Egyptian architects.

Ancient Egypt

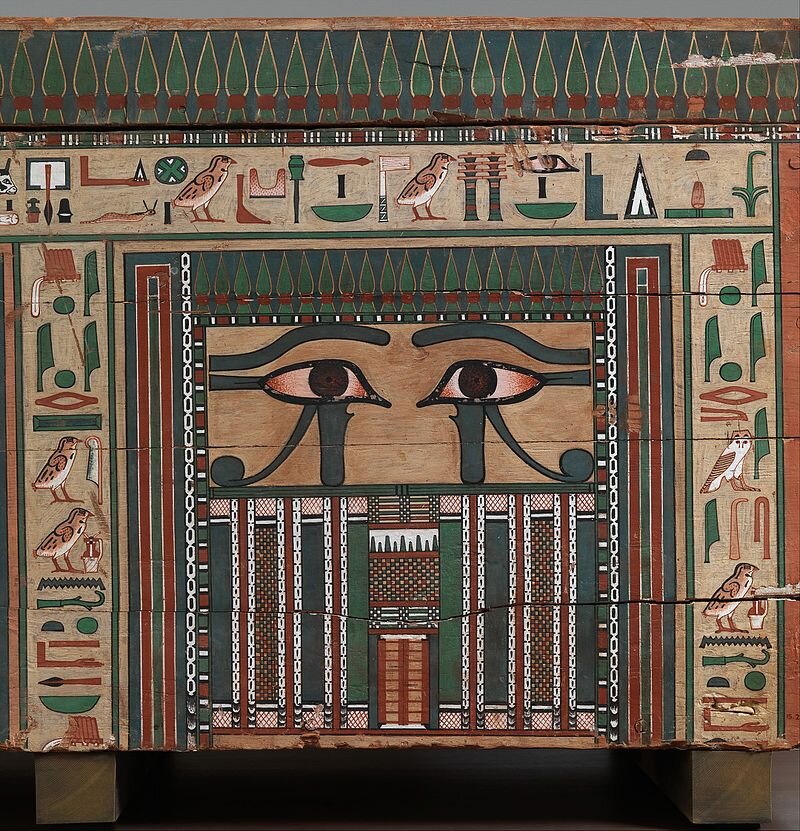

The ancient Egyptians believed that the false door was a threshold between the worlds of the living and the dead and through which a deity or the spirit of the deceased could enter and exit.

The false door was usually the focus of a tomb's offering chapel, where family members could place offerings for the deceased on a special offering slab placed in front of the door.

Most false doors are found on the west wall of a funerary chapel or offering chamber because the Ancient Egyptians associated the west with the land of the dead. In many mastabas, both husband and wife buried within have their own false door.

A typical false door to an Egyptian tomb. The deceased is shown above the central niche in front of a table of offerings, and inscriptions listing offerings for the deceased are carved along the side panels.

Structure

A false door usually is carved from a single block of stone or plank of wood, and it was not meant to function as a normal door. Located in the center of the door is a flat panel, or niche, around which several pairs of door jambs are arranged—some convey the illusion of depth and a series of frames, a foyer, or a passageway. A semi-cylindrical drum, carved directly above the central panel, was used in imitation of the reed-mat that was used to close real doors.

The door is framed with a series of moldings and lintels as well, and an offering scene depicting the deceased in front of a table of offerings usually is carved above the center of the door. Sometimes, the owners of the tomb had statues carved in their image placed into the central niche of the false door.

Historical development

The configuration of the false door, with its nested series of doorjambs, is derived from the niched palace façade and its related slab stela, which became a common architectural motif in the early Dynastic period. The false door was used first in the mastabas of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (c. 27th century BC) and its use became nearly universal in tombs of the fourth through sixth dynasties. During the nearly one hundred and fifty years spanning the reigns of the sixth Dynasty pharaohs Pepi I, Merenre, and Pepi II, the false door motif went through a sequential series of changes affecting the layout of the panels, allowing historians to date tombs based on which style of false door was used.

After the First Intermediate Period, the popularity of the false doors diminished, being replaced by stelae as the primary surfaces for writing funerary inscriptions.

Representations of false doors also appeared on Middle Kingdom coffins such as the Coffin of Nakhtkhnum (MET 15.2.2a, b) dating to late Dynasty 12 (ca. 1850–1750 BC). Here, the false door is represented by two wooden doors that are secured with door bolts, bracketed on both sides by architectural niching - recalling earlier niched temple and palace façades such as the enclosure wall that surrounds the mortuary complex of king Djoser of the Third Dynasty. In a similar manner to the Old Kingdom false doors, representations of false doors on Middle Kingdom coffins facilitated the movement of the deceased's spirit between the afterlife and the world of the living.

Left-hand side of the Coffin of Nakhtkhnum showing the Middle Kingdom equivalent of the Old Kingdom False Door..

Inscriptions

The side panels usually are covered in inscriptions naming the deceased along with their titles, and a series of standardized offering formulas. These texts extol the virtues of the deceased and express positive wishes for the afterlife.

For example, the false door of Ankhires reads:

The scribe of the house of the god's documents, the stolist of Anubis, follower of the great one, follower of Tjentet, Ankhires.

The lintel reads:

His eldest son it was, the lector priest Medunefer, who made this for him.

The left and right outer jambs read:

An offering which the king and which Anubis,

who dwells in the divine tent-shrine, give for burial in the west,

having grown old most perfectly.

His eldest son it was, the lector priest Medunefer,

who acted on his behalf when he was buried in the necropolis.

The scribe of the house of the god's documents, Ankhires.

The Extraordinary Egyptian 'Offering Table of Defdji' that Resembles an Aircraft Control Panel!

What was the use of the extraordinary egyptian 'offering table of Defdji' that resembles a control table of a modern aeroplane?

The round ‘offering table of Defdji’ is a rarity, the majority of offering tables being rectangular. Sometimes the table comes in the shape of the hieroglyph for ‘offering’ - ‘hetep’ in Egyptian – a reed mat with a loaf of bread on it. This round offering table of Defdji’s is extraordinarily detailed. Defdji was an official possessing prominent titles: ‘Acquaintance of the King, Highly Revered by the Great God, Unique Friend, Great One of the Upper Egypt.’

The offering table is made of white alabaster and is 13 cm thick. The hetep sign has been placed in raised relief, horizontally across the middle. Above the sign there are two dishes, and underneath two little vases and a jug in a bowl. The whole surface is divided into little compartments, each of which features the name of a dish, a drink, or a purifying agent. There are over ninety products in total.

In the top panel seven shallow cavities have been made, each intended to hold a special, consecrated oil. With these seven different oils the cult statue of the deceased was anointed. They are precisely named: from right to left they are ‘festive ointment’, ‘laudation oil’, ‘balm’, ‘nekhenem oil’, ‘Tuawet oil’, ‘top quality cedar oil’ and ‘top quality Libyan oil’. To the right of each little cup it is clearly stated again for whom it is destined: ‘for Defdji’.

It dates back to 2,200 BC and it belongs to Leiden Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Ouheden), Netherlands.

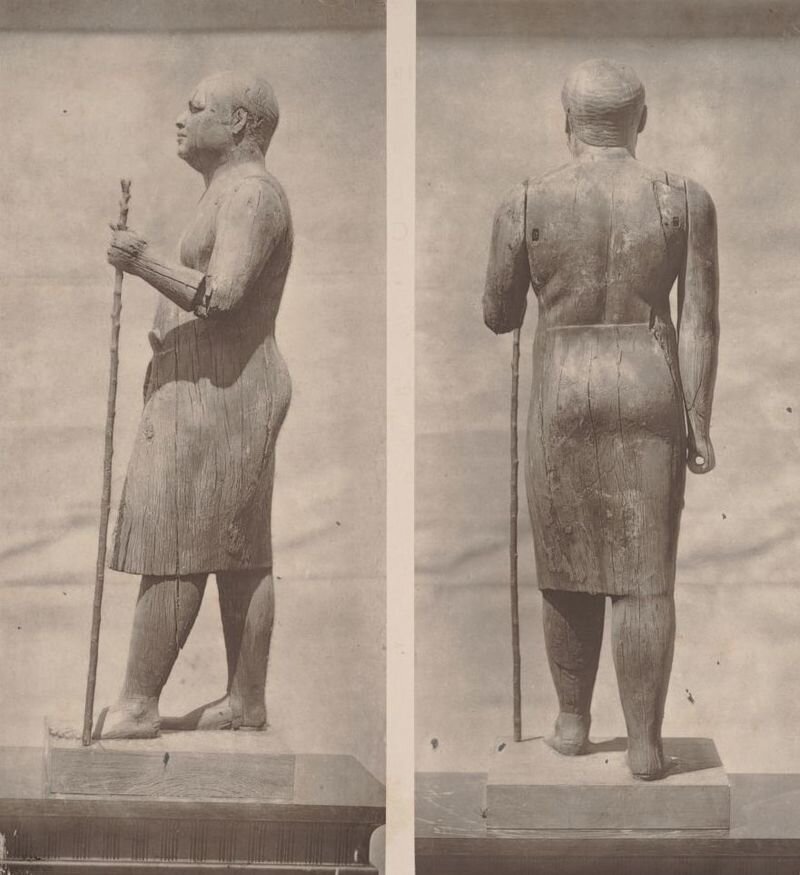

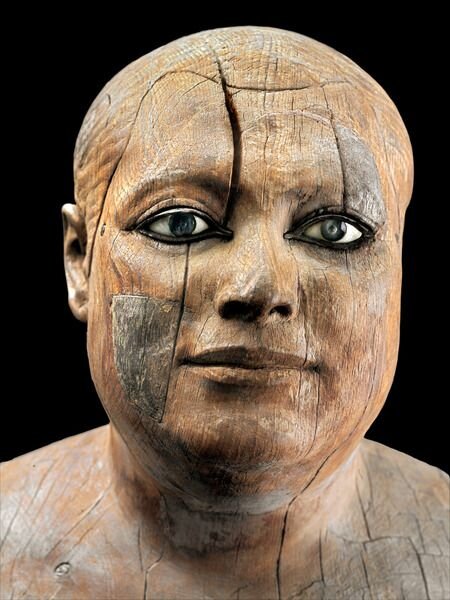

The 'Ka-aper': A 4,500-Years-Old Unique Wooden Statue of the Egyptian Antiquity

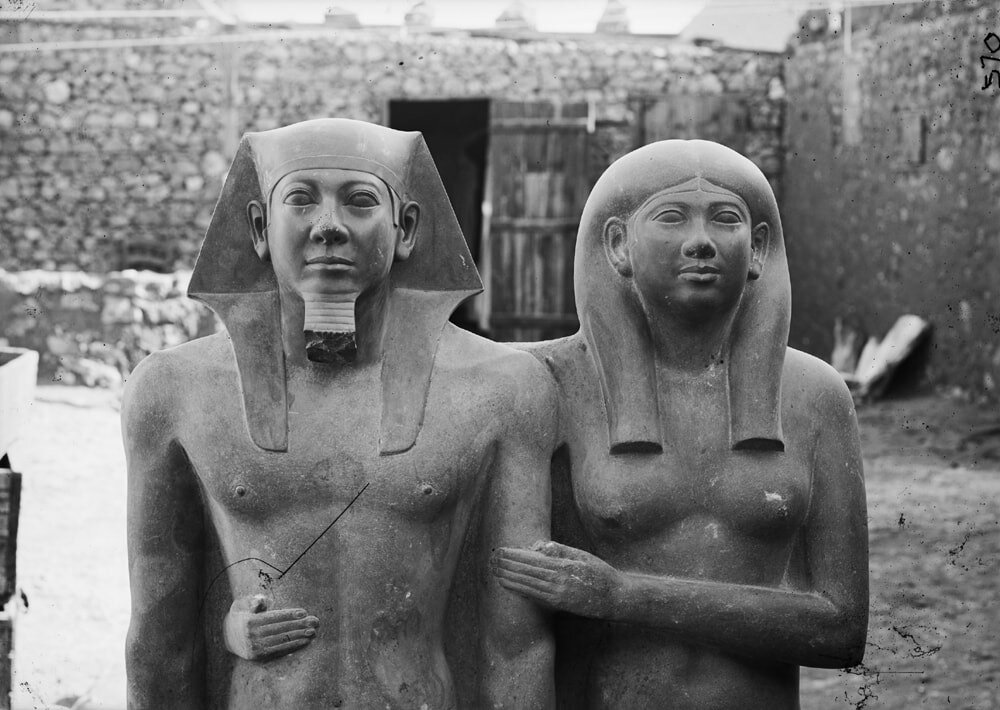

The number of wooden statues that survived from ancient Egypt is very small, compared to their stone counterparts. The reasons behind this are that the quality of local wood was poor. High-quality wood, such as cedar, had to be imported from places like Lebanon. Another reason is that wood does not survive the as well as stone. Many wooden statues probably disintegrated through time.

The statue of Ka'aper was found in excellent condition in his tomb (called a mastaba) within the Saqqara necropolis. It dates to the 5th dynasty of the Old Kingdom, circa 2500 BCE.

This beautiful piece was made for the priest-reader, Ka-aper. It was originally plastered and painted. He is represented in a striding pose, with his left foot forward, and holding a staff (now substituted with a copy) in his left hand. His right would have probably held a cylinder. The level of realism with which the subject is represented is impressive, and contrasts with the extreme idealism in which kings and members of the royal family were depicted.

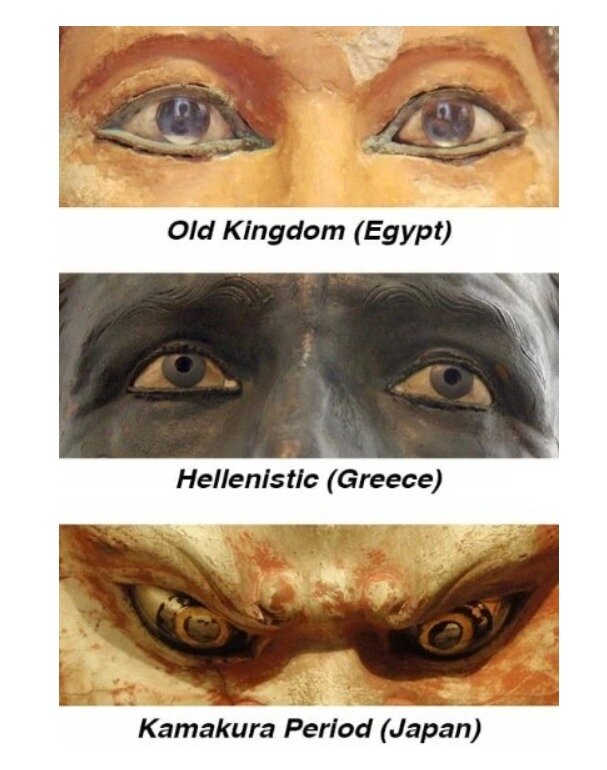

Ka-aper is shown as a corpulent man, probably reflecting his affluent status. His eyes are inlaid with calcite, rock crystal and black stone, outlined with copper, in imitation of eye make-up. These exquisite eyes and the portrait-like facial features add to the life-like quality of this statue, that when the workmen in Mariette’s excavations discovered it they thought it resembled the mayor of their village so much, that the statue was coined “Sheikh el-Balad” (mayor), a name by which this statue is still known today, even by non-Egyptians.

Today, the famous statue of Ka'aper is held at The Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Egypt. Many other gorgeous examples of Egyptian art can be found at the world-famous institution.

The 'Seated Scribe' - A Famous Work of Ancient Egyptian Art

The sculpture of the Seated Scribe or Squatting Scribe is a famous work of ancient Egyptian art. It represents a figure of a seated scribe at work. The sculpture was discovered at Saqqara, north of the alley of sphinxes leading to the Serapeum of Saqqara, in 1850 and dated to the period of the Old Kingdom, from either the 5th Dynasty, c. 2450–2325 BCE or the 4th Dynasty, 2620–2500 BCE. It is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

It is a painted limestone statue, the eyes inlaid with rock crystal, magnesite (magnesium carbonate), copper-arsenic alloy, and nipples made of wood.

This painted limestone sculpture represents a man in a seated position, presumably a scribe. The figure is dressed in a white kilt stretched to its knees. It is holding a half rolled papyrus. Perhaps the most striking part aspect of the figure is its face. Its realistic features stand in contrast to perhaps more rigid and somewhat less detailed body. Hands, fingers, and fingernails of the sculpture are delicately modeled. The hands are in writing position.

Special attention was devoted to the eyes of the sculpture. They are modeled in rich detail out of pieces of red-veined white magnesite which were elaborately inlaid with pieces of polished truncated rock crystal. The back side of the crystal was covered with a layer of organic material which at the same time gives the blue colour to the iris and serves as an adhesive. Two copper clips hold each eye in place. The eyebrows are marked with fine lines of dark organic paint.

The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking. He has a ready-made papyrus scroll laid out on his lap but the reed-brush used to write is missing. Both his hands are positioned on his lap. His right hand is pointing towards the paper as if he has already started to write while watching others speak. He stares calmly at the viewer with his black outlined eyes.

The sculpture of the seated scribe was discovered in Saqqara on 19 November 1850, to the north of the Serapeum's line of sphinxes by French archeologist Auguste Mariette. The precise location remains unknown, as the document describing these excavations was published posthumously and the original excavation journal has been lost.

Egyptian Archaeologists Accidentally Discover 250 Ancient Rock-Cut Tombs

Some of the burials found at the Al-Hamidiyah necropolis date back 4,200 years

The rock-cut tombs are carved into different levels of a mountain face at the site. (Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities)

An archaeological survey crew accidentally discovered some 250 rock-cut tombs at the Al-Hamidiyah necropolis near Sohag, Egypt. The graves range in age from the end of the Old Kingdom around 2200 B.C. to the end of the Ptolemaic period in 30 B.C., according to Nevine El-Aref of Ahram Online.

Several styles of tombs and burial wells are carved into different levels of a mountain face at the site, says Mustafa Waziri, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, in a statement from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The necropolis is located in southern Egypt, on the West Bank of the Nile River.

One of the burials includes a sloping tomb with a false door and a hallway leading to a gallery with a shaft. The door is inscribed with hieroglyphs depicting the resident of the tomb slaughtering sacrifices while mourners make offerings to the deceased.

“Given their small size compared with the tombs reserved for royalty, which are of large sizes, these tombs may have been allocated to the common people,” historian Bassam al-Shamaa tells Ahmed Gomaa of Al-Monitor. “This provides more details about the daily life of ordinary people at the time.”

Archaeologists conducting excavation work at the necropolis discovered numerous pottery shards and intact pots. Some of the pieces were used in daily life, while others, known as votive miniatures, were crafted for funerary purposes, says Mohamed Abdel-Badiaa, head of the Central Department of Antiquities for Upper Egypt, in the statement.

Finds made at the site include pottery fragments and animal bones. (Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities)

The team also found remnants of a round metal mirror, human and animal bones, small alabaster pots, amphorae fragments dated to Egypt’s Late Period (c. 664 to 332 B.C.), and pieces of limestone funerary plates dated to the Sixth Dynasty (c. 2345 to 2181 B.C.).

Badiaa and his colleagues expect to find more rock-cut tombs at the site as excavations continue. Per the statement, they have already documented more than 300 tombs in the area, which was centrally located near the ancient cities of Aswan and Abido.

Use of the burial site spans more than 2,000 years, beginning in the Old Kingdom period, which included Pharaoh Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The last interments likely occurred around the time of Cleopatra’s death in 30 B.C., which marked the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

The Al-Hamidiyah necropolis is believed to have been the final resting place for leaders and officials of the city of Akhmim, one of the most important administrative centers in ancient Egypt, reports Jesse Holth for ARTnews. Akhmim was home to the cult of Min, a god of fertility and sexuality who was also associated with the desert, according to Ancient Egypt Online.

Finds made at the site may pave the way for future discoveries at oft-overlooked archaeological sites, Badiaa tells Al-Monitor.

“Egypt has many antiquities sites, but light must be shed on other unknown areas,” he adds. “[Excavations] should not be limited to famous archaeological areas such as Saqqara or Luxor.”

By David Kindy, SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

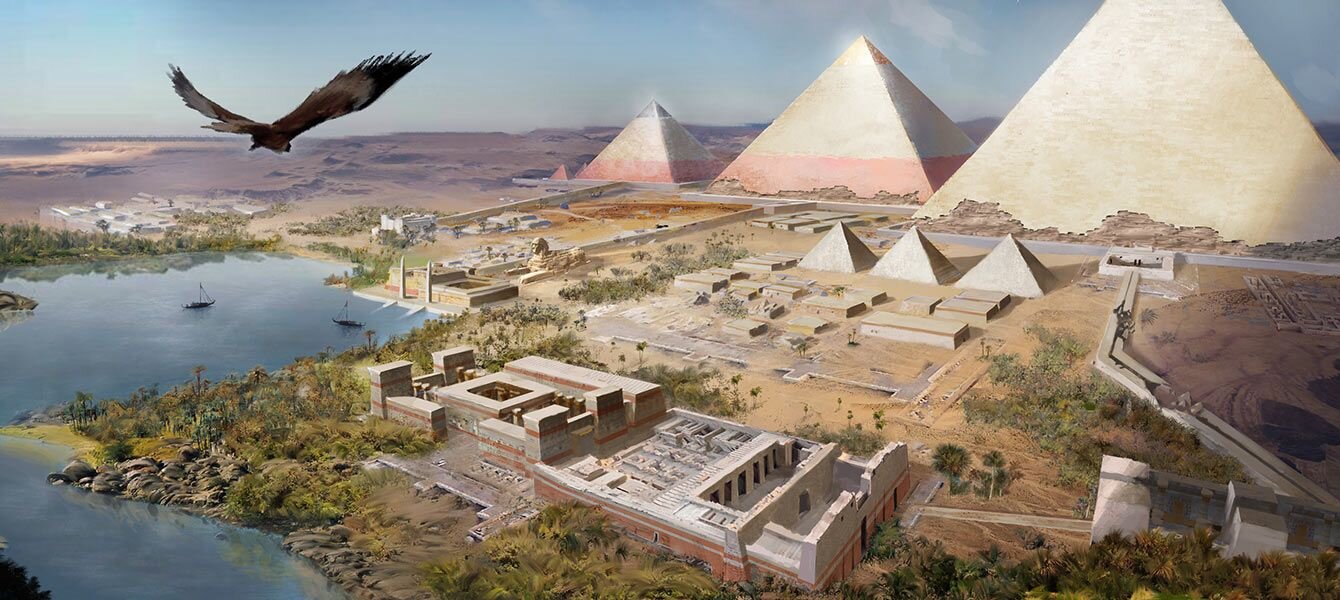

Three Egyptologists Use Assassin's Creed Origins To Teach History

Assassin’s Creed Origins’ rendition of Ptolemaic Egypt is one of the most accurate interactive representations of the period, so much so that Egyptologist Dr. Chris Naunton referred to it as “the best visualization of ancient Egypt.” Naunton’s remark came during the first episode of “Playing in the Past” a six-part series dedicated to looking at Egyptian history through the lens of Assassin’s Creed Origins. The series is broadcast on Twitch, where Naunton was joined by a PhD student at Southampton University, Gemma Renshaw, and associate professor of history at Missouri University of Science and Technology, Dr. Kate Sheppard.

The Giza Pyramid Complex, also called the Giza Necropolis, the site on the Giza Plateau.

Together, the three Egyptologists took viewers through a tour of Thebes. Naunton began by comparing photos from his travels to vistas in the game before taking up the reins himself and moving throughout the world on his own.

The world of Assassin’s Creed Origins was already the focus of the post-launch Discovery Tour by Assassin’s Creed – Ancient Egypt, which turns Ptolemaic Egypt into a living museum complete with guided tours. To find out what experts in the field think about Origins’ depiction of Egypt and why they decided to livestream their lectures, we spoke with Renshaw, Sheppard, and Naunton.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria and a panoramic view of the Hellenistic city.

Where did the idea for “Playing in the Past” come from? What made you want to stream it to the public?

Chris Naunton: Last summer, I was writing a book for children about Cleopatra, which is going to be called “Cleopatra Tells All,” and I was at the stage where I needed to give the illustrator ideas for what I specifically wanted Alexandria to look like. I wanted to be able to send him stuff saying, “Look, this is what it looked like.”

So I was Googling for images of visualizations of Alexandria, and I knew that there was a guy called Jean-Claude Golvin, a French artist who had painted a load of reconstruction drawings of various places in the ancient world, including in Egypt and Alexandria, but I wasn't finding them. What I was finding were all these things from this videogame called Assassin's Creed Origins.

I kept asking, “What’s this?” “How can I get this?” So eventually I just posted something on Twitter saying, “Look, can somebody tell me how I can get this game?”, because at this point I've discovered there's such a thing as a Discovery Tour, so I don't even have to be able to play the game, I can just walk around.

I can tell it looks amazing, and eventually Gemma just responds – we know each other from Twitter and various other things over the years – and she says, “I've got it, I could show you around if you like.”

At the same time, Kate and I were doing our own podcast together, which was a kind of virtual trip up the Nile from the perspective of historic travelers, Europeans mostly. So when Gemma had offered to show me around, Kate wanted to join in too.

Kate Sheppard: When Gemma responded, I just sort of virtually elbowed my way in, and we all sort of met, and Chris and I were just asking her to show us around all of these places.

Gemma Renshaw: I put it on my Twitch channel. I had never streamed before, but thankfully, I had some assistance from a kind friend of mine. I got it working on Twitch, and then I just streamed it for a bit so that they could see it, and then we could go and look at stuff together, and we sort of talked about things on Twitter. At that point, other people started to show interest.

At first, I just wanted to let Chris look at what he wanted to look at for his book. But there was enough interest from people that I thought, “Why don't we just do another one and invite everyone?” So we did it in September last year, and it wasn't quite the same format that we're doing “Playing in the Past” now.

Deir el Medina tombs.

How familiar were you with videogames before all of this?

CN: I had a Sega Master System II in the early ‘90s, but that was pretty much the last time I played a videogame, and I just thought this was not for me. I bought an Xbox in the middle of all of this because I was so taken with this whole idea, and I wasn't even sure if I would be able to work the controller, but I still thought, “I want to be able to explore this myself.” Once I'd run around a little bit, I just thought, “this is amazing.”

At what point did you decide to make this a formal series?

GR: After we did the September run, we decided that we would apply to Southampton University to see if they would give us any funding. And they did! That’s when we called it “Playing in the Past” and really ironed out the idea. Funding means that we can pay other experts to come and be a part of it.

In archaeology, we try to get people to imagine what monuments were like when they don’t exist anymore, but a lot of people can’t do that. Same for things that exist only as ideas or beliefs. Having the opportunity to do things like go into the underworld and show people an interpretation is really useful.

Graphic Reconstruction of the ancient egyptian pyramids in Asassin’s Creed Origins.

On one of my streams, I had a long conversation with someone in chat, and one of the things they said was, “I had no idea that academics liked games.” And I said, “Some of them might not, but some do, and there’s no reason why we can’t connect the two things.” We’ve proven that it can work, and work well.

CN: I’m freelance, so I’m used to there not being much money involved, but I hadn't realized how pleased I was going to be and how cool it would be to be able to say, “This is now a university-funded project.” It’s not just three people who like archaeology and games; people have to recognize now that this is a real thing.

Map of ancient Egypt as shown in Ubisoft’s game.

I'm really proud of it, and being able to visit these places which are so well depicted – I just thought, if I like it, I'm sure there's going to be a lot of people out there that will want to do this too. I think that's been borne out in the numbers we've been getting, and the enthusiasm we've been getting for this, too.

KS: Chris and Gemma are much more public-facing than I am with my students, who are generally 18 to 22 years old. Here at my university, we have a nationally ranked esports team, so many of my students are very into videogames. They love them, and so when we're doing history of science, I was talking about eugenics, and I had loads of students asking if I had ever played Bioshock.

‘Bayek’ approaching the massive temple gates of Memphis in Assassin's Creed Origins.

That’s when I started thinking I really need to get into some of these videogames, because they keep telling me about them, and this is a way I can connect with them. If we get into that mode of “here's how we can connect to people,” then maybe we can at least bring in new people who might be interested. If we as scholars aren't talking to the general public, and we're just talking to this tiny little bubble of people, what's even the point?

Gemma, you’re a fan of the Assassin’s Creed franchise. Did it help you get interested in history at all?

GR: Yeah! I think I relate quite well to the people who are going to watch the stream, because they can ask me questions about Egypt and history, or they can be about the game, and I might know the answer to that too.

I loved not only the stories, but the database entries that were included going way back to Assassin’s Creed II. I really appreciated how they tried to include history and weave the story around the history in a way that was believable. I think it certainly made me want to find out more about the actual history that was behind it. I have to confess that I didn't really know anything about the Medici family until I played Assassin's Creed II, and then I wanted to learn about them.

Alexander The Great's Tomb in Alexandria with his body embalmed in a coffin filled with honey.

When Assassin's Creed Origins first came out, I didn't play it immediately, but I bought it for myself for Christmas one year, and then played it so much for about two weeks that I didn’t even speak to my roommate.

How does it feel to virtually explore a real-life location that you know so well?

KS: I think the only bad thing is that it really makes me want to be there. The thing that makes me emotional about it and love it so much are the little details. You look down at the ground, and the stones look the same as they do in real life, and you can imagine yourself being there.

You can almost feel the sun on you, and you can sort of smell it. You just kind of breathe it in, and it's just like, “Ah, OK, I'm back, I'm here” and you can almost get that when you're playing the game, and that's what I love about it.

An artist rendering of life on the Nile river in Assassin's Creed Origins.

CN: I think something we worry about is the level of representation, because there are so many movies that are so inaccurate and misleading. People always assume I love those kinds of movies, but I can barely watch them. Going into Origins, I had already seen enough photos to know that it was going to be great.

I had gamer friends who would say “There's this new game coming out. It's called Assassin's Creed Origins. You'd love it,” and I was like, “Yeah, sure, I don’t really do games.” I think that’s probably how most academics would think about it initially, but now I’m committed. It’s made me a gamer in a way; when I’m not in Ancient Egypt, I'm on the forest moon of Endor!

The real jaw-dropping moment for me was running up to the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri, which is the same, minus any of the modern clutter that's there today. They took out the ticket office and the tarmac, but it’s all the same. It does make you want to be there, but I almost want to say it’s a little bit better.

I also want to say that the representation doesn't need to be that good. I'm just running around like a sort of maniac, just running up hills and things and looking down on temples, and there's so much detail in there, I can't believe how amazing it is. We went hours over our planned stream time for our first stream because I just kept wanting to wander.

‘Bayek’ approaching The Great Temple of Ramesses II in Abu Simbel.

Chris, you mentioned the Temple of Hatshepsut. Is there anything in particular that really impressed you with regard to the historical representation?

CN: For me, it’s the fact that it is very specifically this particular moment at the end of the Ptolemaic period, which is a very interesting time in terms of what Egypt would have looked like. You have the broken paving stones in Alexandria, and it would have just been easier to put in new paving stones, wouldn't it? That sort of level of detail is amazing.

Then you have the monuments, [some of] which are recognizable in a kind of half-state of decay, and others a bit better maintained. There are the brand-new sort of late-Ptolemaic Roman-influenced buildings coming up, and then the people who are clearly foreigners, as well as that mixture of a more traditional Egyptians. You also have a newer kind of Hellenistic Egypt, or even just purely foreign Greek influence. I mean, the ambition to do that is really super-impressive.

‘Bayek’ and his eagle approaching The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, also known as the Djeser-Djeseru (Ancient Egyptian: "Holy of Holies").

KS: In one of our later streams, we’re looking at ancient crafts. We’re having an expert, Dr. Sarah K. Doherty, come on for it, but we were just chatting with her, and she was talking about how usually, if you see a bread maker, there's going to be a beer maker right nearby because of the yeast. They use similar ingredients, and so they would share, and it would be easier for them both. Then we were in game and walking by a bakery, and, wouldn’t you know, right next to it is a brewery. That part, to me, really stuck out.

GR: One of the things I’m impressed with in all Assassin’s Creed games is the quality of the light. It's really clear that people at Ubisoft have visited all of these places and made an effort to make the places feel different and close to real life. The light in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla is so different from the light in Origins, as it should be.

Your first stream focused on Thebes, an area not available as part of Discovery Tour. Have you used Discovery Tour at all? What are your thoughts on it?

GR: We actually tried to do that in our stream back in September. We tried to take the Step Pyramid tour, but the problem with us doing it that way was that we kind of wanted to talk when the game was talking, so it ended up being a bit difficult. I did let all the people watching the stream know about it so they could do it on their own.

CN: I think Discovery Tour is great, but it was slightly tricky to do it live. To some extent, it's sort of duplicating the kinds of things we could offer in the livestream anyway. I would recommend it to people though, and I loved the pop-ups that would show the genuine real objects which are described in the tours that you can read more about. As if proof were needed that the game is based on good solid research, it's right there.

Thebes city overall silhouette, by Martin Bonev (full representation here).

I was exploring the west bank in Thebes on our stream, and everything is where it should be. If you're familiar with that part of the world [like I am], you don't need to be told where things are, because they're where they should be.

When I watched the stream, I noticed that you almost never brought up the map for navigation purposes. Were you able to just find your way around because you knew were everything was?

CN: Well, I mean, to some extent, yeah. The landscape is as it should be. The roads and hills, and even the topography is more or less accurate. I didn't need a map to find where things were, because they’re all in the right place.

Temple of Luxor by night, by Martin Bonev (full representation here).

One last question for you all. Obviously, you're all Egyptologists, but since Assassin’s Creed has already been to Egypt, is there another setting you’d like to see it explore?

GR: I have a few. I'm going to say Kingdom of Mali around 13th-16th century AD, Silk Road Mongolia around 12th-13th century AD, or the Khmer Empire, ideally set in around 12th 13th century AD, when Angkor Wat was built. There are so many potential answers to this, and realistically I am likely to play whatever is chosen - but personally I would like to see exploration of some wider world history rather than Western-focused ones. I will, however, give a (dis)honorable mention to the time of Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, up to around 1850. Maybe as a DLC to either Origins or Unity, as it's a time period that Chris, Kate, and I all know quite a bit about. I also think players would be fascinated to visit the places they have in Origins, but with a 19th-century make over.

CN: Mexico at the very end of the Aztec civilization at the time of the Spanish conquistadors. The idea of a monumental civilization being invaded by technologically and militarily superior Europeans echoes the story in Origins. And it would look AMAZING.

KS: I agree with Mexico, or the Inca in Peru. The Mississippian cultures like the Mound Builders and Cahokia, or the American Westward expansion during the gold rush too. It would be an interesting perspective on how terribly white people treated and exploited the peoples and the natural world on the way out.

More of massive graphic reconstructions of Hellenistic Egypt:

Graphic Reconstruction of the Djoser’s Step Pyramid Complex in Saqqara.

Graphic Reconstruction of the Pyramid of Amenemhet III at Hawara.

A mastaba or pr-djt (meaning "house of stability", "house of eternity" or "eternal house" in Ancient Egyptian) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks.

These edifices marked the burial sites of many eminent Egyptians during Egypt's Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. In the Old Kingdom epoch, local kings began to be buried in pyramids instead of in mastabas, although non-royal use of mastabas continued for over a thousand years. Egyptologists call these tombs mastaba, from the Arabic word مصطبة (maṣṭaba) "stone bench".

The city of Amarna is an extensive archaeological site that represents the remains of the capital city newly established (1346 BC) and built by the Pharaoh Akhenaten of the late Eighteenth Dynasty, and abandoned shortly after his death (1332 BC).

Cyrene is depicted in Assassin's Creed: Origins to be much closer to Alexandria than it was in reality. It was actually located almost 500 miles west, near the modern-day village of Shahhat in Libya.

By Ubisoft

Secrets of the Dead: Temple of Kom Ombo & Crocodile Museum

Standing on a promontory at a bend in the Nile, where in ancient times sacred crocodiles basked in the sun on the riverbank, is the Temple of Kom Ombo, one of the Nile Valley's most beautifully sited temples. Unique in Egypt, it is dedicated to two gods; the local crocodile god Sobek, and Haroeris (from har-wer), meaning Horus the Elder.

Temple in Kom Ombo - Sachin Vijayan Photography/Getty Images

The temple's twin dedication is reflected in its plan: perfectly symmetrical along the main axis of the temple, there are twin entrances, two linked hypostyle halls with carvings of the two gods on either side, and twin sanctuaries. It is assumed that there were also two priesthoods. The left (western) side of the temple was dedicated to the god Haroeris, and the right (eastern) half to Sobek.

Reused blocks suggest an earlier temple from the Middle Kingdom period, but the main temple was built by Ptolemy VI Philometor, and most of its decoration was completed by Cleopatra VII’s father, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos. The temple’s spectacular riverside setting has resulted in the erosion of some of its partly Roman forecourt and outer sections, but much of the complex has survived and is very similar in layout to the Ptolemaic temples of Edfu and Dendara, albeit smaller.

Touring the Temple

Passing into the temple’s forecourt, where reliefs are divided between the two gods, there is a double altar in the centre of the court for both gods. Beyond are the shared inner and outer hypostyle halls, each with 10 columns. Inside the outer hypostyle hall, to the left is a finely executed relief showing Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos being presented to Haroeris by Isis and the lion-headed goddess Raettawy, with Thoth looking on. The walls to the right show the crowning of Ptolemy XII by Nekhbet (the vulture-goddess worshipped at the Upper Egyptian town of Al Kab) and Wadjet (the snake-goddess based at Buto in Lower Egypt) with the dual crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, symbolising the unification of Egypt.

Reliefs in the inner hypostyle hall show Haroeris presenting Ptolemy VIII Euergetes with a curved weapon, representing the sword of victory. Behind Ptolemy is his sister-wife and coruler Cleopatra II.

From here, three antechambers, each with double entrances, lead to the sanctuaries of Sobek and Haroeris. The now-ruined chambers on either side would have been used to store priests’ vestments and liturgical papyri. The walls of the sanctuaries are now one or two courses high, allowing you to see the secret passage that enabled the priests to give the gods a ‘voice’ to answer the petitions of pilgrims.

The outer passage, which runs around the temple walls, is unusual. Here, on the left-hand (northern) corner of the temple’s back wall, is a puzzling scene, which is often described as a collection of ‘surgical instruments’. It seems more probable that these were some of the accoutrements used during the temple’s daily rituals, although the temple was certainly a place of healing, the nearest thing to an ancient hospital.

Near the Ptolemaic gateway on the southeast corner of the complex is a small shrine to Hathor, while a small mammisi (birth house) stands in the southwest corner. Beyond this to the north you will find the deep well that supplied the temple with water, and close by is a small pool in which crocodiles, Sobek’s sacred animal, were raised.

Mummified Crocodiles at Kom Ombo

The path out of the complex leads to the new Crocodile Museum. It's well worth a visit for its beautiful collection of mummified crocodiles and ancient carvings, which is well lit and well explained. The museum is also dark and air-conditioned, which can be a blessing on a hot day.

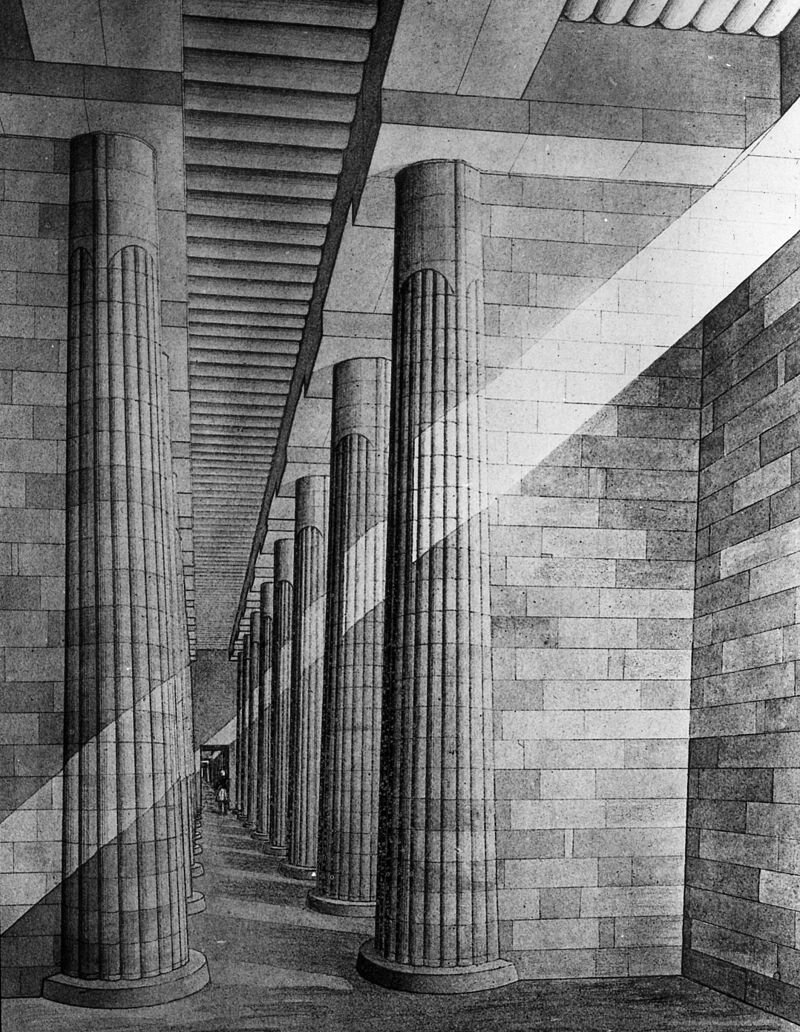

Egypt: The Colonnade Entrance Of Djoser Complex that Looks Like a Greek Dorian Temple!

There are many theories as to the origins of the Doric order in temples. One belief is that the Doric was inspired by the architecture of Egypt. With the Greeks being present in Ancient Egypt as soon the 7th-century BC, it is possible that Greek traders were inspired by the structures they saw in what they would consider foreign land.

Left: The Colonnade Entrance Of Djoser Complex in Saqqara, Egypt Right: Temple Of Apollo In Ancient Corinth, Greece

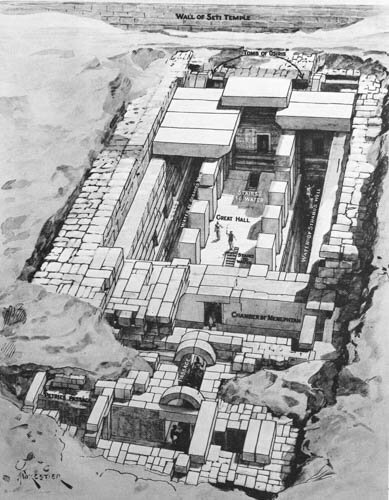

The funerary complex of Djoser (Zoser) is believed to have been built around the beginning of the 3rd Dynasty. It is a walled compound that is constructed from stone rather than the mud brick that was used before this time. The stones that are used are different from the huge stones used in the pyramids at Giza, in that they are small in size. Imhotep was the architect of this revolutionary wonder. He was later worshipped as a god for the remarkable craftsmanship in the complex. Imhotep translated into stone the early Egyptian architecture of mud-brick, wood and reeds. This is seen in many of the monuments that are in the complex.

The entire complex was once surrounded by an enclosure wall, that when complete, was about 600 yards (549m) long and 300 yards (274m) wide and rose to over 30 feet (9.1m). The wall is made of brick-size stones and is very impressive in its own right. Just the size alone would have made the wall an incredible project, but that is not the only thing impressive about this enclosure wall.

Funerary Complex of Djoser

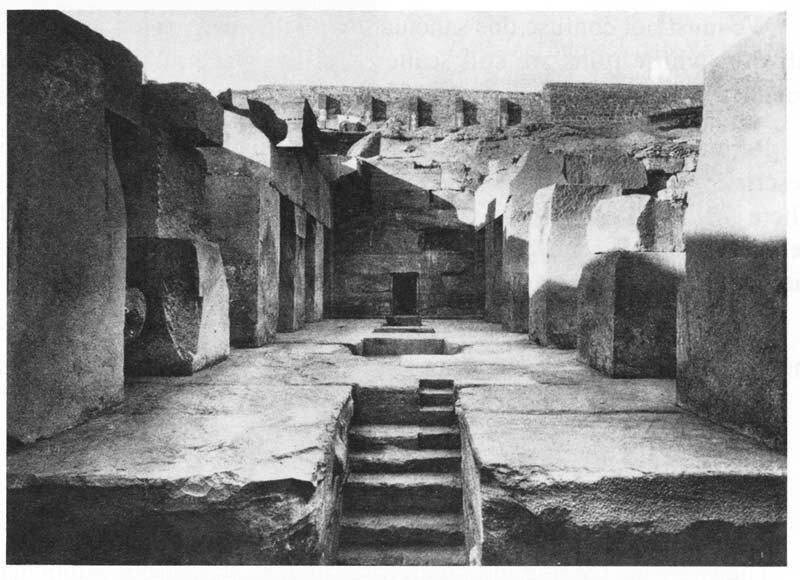

The single entrance to the enclosure is the southernmost doorway on the eastern side of the wall (the only one of the 15 doorways which is not a false door) and leads to the entrance colonnade. 20 pairs of engaged columns, resembling bundles of reeds or palm ribs line the corridor. Between the columns are 24 small chambers, thought perhaps to represent the nomes of Upper and Lower Egypt, which may once have contained statues of the King or deities.

The exit point from the Hypostyle Hall and Enclosed Portico. View looking East from the Great Court.

The roof of the entrance colonnade was constructed to represent whole tree trunks. This is one of the places where the challenging experiment of copying natural materials in stone is most evident. The columns were not yet trusted to support the roof without being attached to the side walls and the small size of the stone blocks used in the construction reflects the fact that previous structures were built from mudbricks.

At the end of the entrance hall two false stone doorleaves rest against the side walls of a transverse vestibule which has been reconstructed. Several statue fragments were found in the entrance colonnade but the most important was a statue base (now in Cairo Museum) inscribed with the Horus name and titles of Netjerikhet and also with the name of a High Priest of Heliopolis and royal architect, Imhotep.

The columns themselves are engaged columns, but unlike later examples where the column is next to a wall (known as pilasters), here the side wall projects out creating bays between each set of columns (often referred to as niches) and are on both the South and North sides of the center asile in both the East and West Hypostyle Halls. Above these bays in the East and West halls, near the roof are horizontally oriented clerestory openings. The columns are 'proud' of these projecting side walls allowing their circular shape to return and engage the geometry of the wall. The circular columns are carved to resemble papyrus bundles and were painted green to resemble the plant. The side walls themselves also taper to ensure that they do not overlap the decorative papyrus relief, but are placed in a common staggered stacking pattern as is the back wall of the bay. The side wall joints are very small and precise and the surface is relatively smooth.

The Greek Doric order

The Doric order was one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognized by the simple circular capitals at the top of columns. Originating in the western Doric region of Greece, it is the earliest and, in its essence, the simplest of the orders, though still with complex details in the entablature above.

Three Greek Doric columns

The Greek Doric column was fluted or smooth-surfaced, and had no base, dropping straight into the stylobate or platform on which the temple or other building stood. The capital was a simple circular form, with some mouldings, under a square cushion that is very wide in early versions, but later more restrained.

When the three orders are superposed, it is usual for the Doric to be at the bottom, with the Ionic and then the Corinthian above, and the Doric, as "strongest", is often used on the ground floor below another order in the storey above.

Two early Archaic Doric order Greek temples at Paestum (Italy) with much wider capitals than later

Origins of the Doric Order

There are many theories as to the origins of the Doric order in temples. The term Doric is believed to have originated from the Greek-speaking Dorian tribes. One belief is that the Doric order is the result of early wood prototypes of previous temples. With no hard proof and the sudden appearance of stone temples from one period after the other, this becomes mostly speculation. Another belief is that the Doric was inspired by the architecture of Egypt. With the Greeks being present in Ancient Egypt as soon the 7th-century BC, it is possible that Greek traders were inspired by the structures they saw in what they would consider foreign land.

Finally, another theory states that the inspiration for the Doric came from Mycenae. At the ruins of this civilization lies architecture very similar to the Doric order. It is also in Greece, which would make it very accessible.

A faithful reconstruction of the Djoser’s Complex Colonnade Entrance as it was during the Hellenistic Period. Screenshots from the Assassin's Creed game by Ubisoft, called Origins. By Nikolay Bonev.

Egypt's Most Significant Archeological Discoveries of 2021

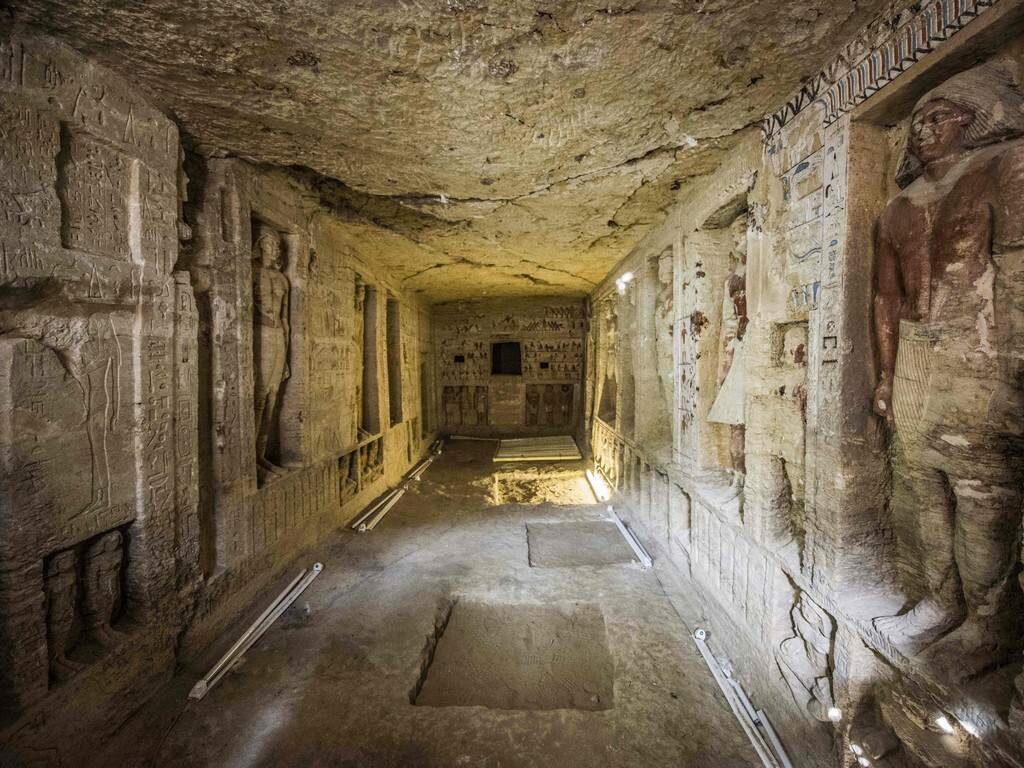

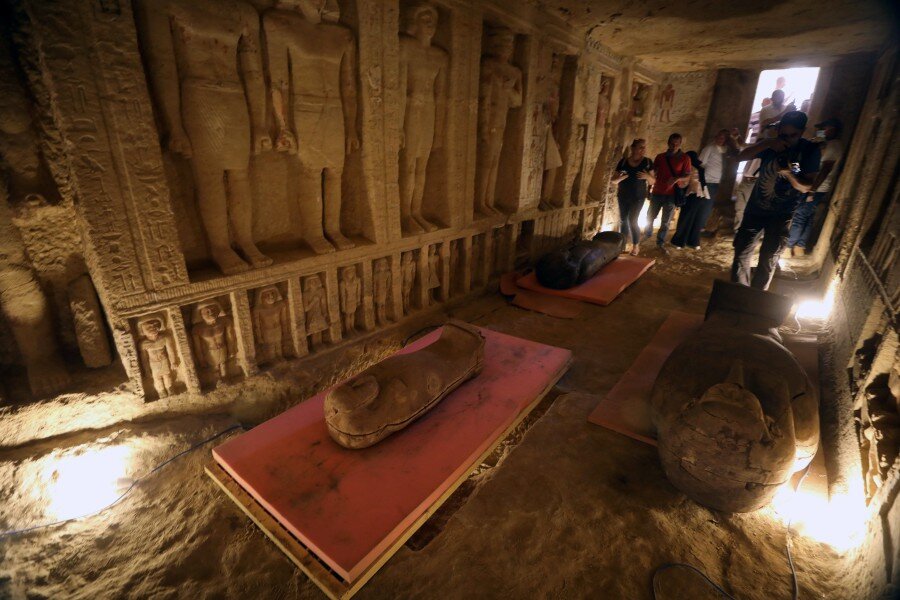

Egypt recently uncovered a significant archaeological discovery that sheds light on secrets in the Saqqara necropolis south of Cairo and on the 18th and 19th Egyptian dynasties.

The unearthed artifacts are a major find that could turn the ancient burial site into a major tourist and cultural destination and revise our understanding of region during the New Kingdom era under King Teti, the first pharaoh of Egypt’s Sixth Dynasty. The burial sites being excavated are around his pyramid.

Prominent archeologist Zahi Hawass told reporters at the Saqqara site on Jan. 17 that the joint Egyptian mission of researchers from the Supreme Council of Antiquities and the Zahi Hawass Institute of Egyptology, unearthed the funerary temple of Queen Nearti, the wife of King Teti, near the pyramid of her husband.

The mission also found plans for the temple's construction and three warehouse-like structures built of mud bricks in the southeast side of the funerary temple, used for storing ritual offerings to the deities.

In addition, 52 burial wells were found, with depths ranging from 10 to 12 meters and containing more than 50 wooden coffins dating back some 3,000 years during the New Kingdom period — a discovery unprecedented in the Saqqara area.

The sarcophagi are carved into human form and bear paintings of several gods as well as funerary writings from the Book of the Dead, which is said to be a guide for the deceased in their journey to the other world.

Several other artifacts were also found inside the wells, including statues of deities such as the gods Osiris, Ptah and Seker.

The archeological mission also unearthed a papyrus four meters long and one meter wide, bearing excerpts from the Book of the Dead and the signature of its owner, Bu-Khaa-Af.

This same name was found on four Ushabti funerary statues. A wooden coffin carved in human form was also found, in addition to other Ushabti statues made of wood and tin-glazed pottery from the New Kingdom era.

A set of wooden masks and a shrine to Anubis, a god of the afterlife, were also uncovered, as well as statues of Anubis found in good condition. Several games left for the dead were also unearthed such as senet, which is very similar to today’s chess, and as set for the Game of Twenty Squares bearing the name of its owner.

Other artifacts included depictions of geese as well as a bronze ax, indicating that its owner was one of the leaders of the army during the New Kingdom era, and paintings depicting scenes of the deceased and their wives and bearing hieroglyphics.

One limestone panel in good condition depicts a man identified as Khu-Ptah and his wife Mut-am-waya. One part of the painting shows the couple worshiping the god Osiris, while the lower part depicts the man seated and his wife sitting behind him with their daughters, one at her mother’s feet holding a lotus flower to her nose.

Hawass said that the excavation works continue and new archeological discoveries can be expected as many of Saqqara's antiquities have not been unveiled.

Sabri Farag, director of the Saqqara archaeological site, told Al-Monitor that the latest discovery is a very important one in the Saqqara necropolis and that the excavation mission is ongoing. He said, “Saqqara has not revealed all its many secrets yet”, adding that the mission uncovered eight archeological finds in 2020 and this new one already in 2021. He said that more discoveries can be expected over the course of the year.

Waad Abu al-Al, director of projects at the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, told Al-Monitor that restoration works are underway in the southern cemetery of King Djoser to open the necropolis for tourists.

“Excavations works in the ancient site are also ongoing and once they're completed, Saqqara will take its place on the world’s tourist map,” he said.

By Alaa Omran

The ‘Lost Egyptian Labyrinth' of Hawara: Is a 2,000-Year-Old Mystery Finally Solved?

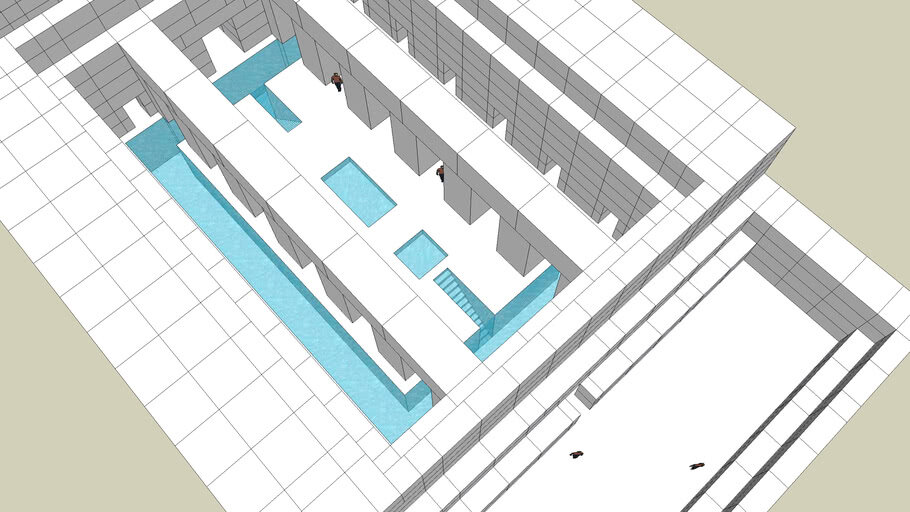

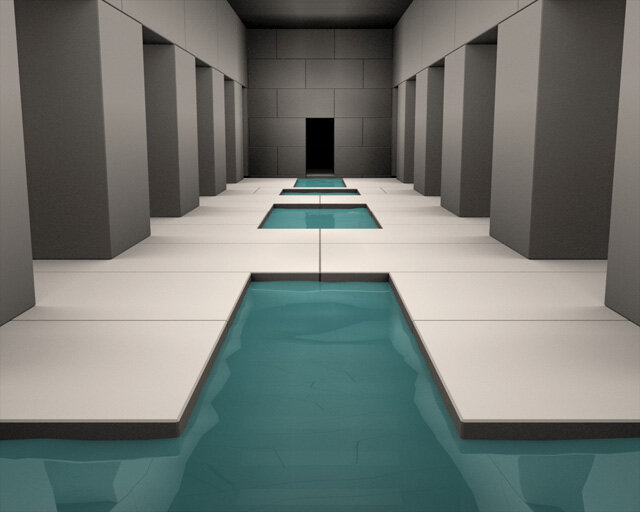

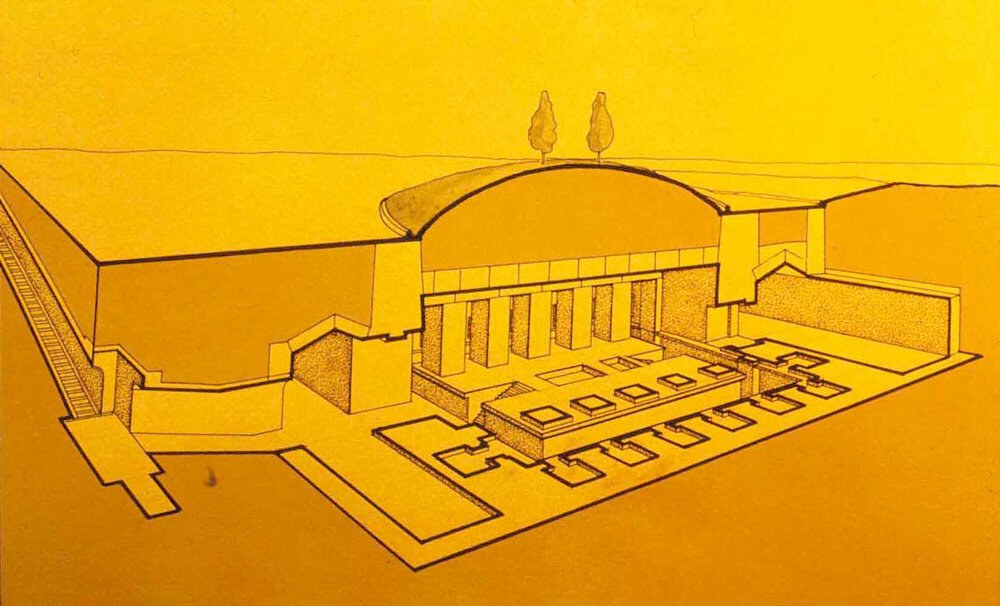

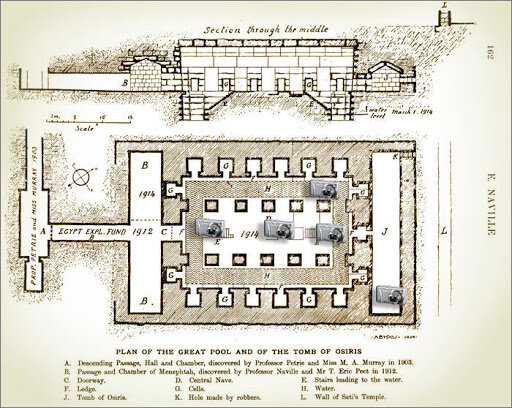

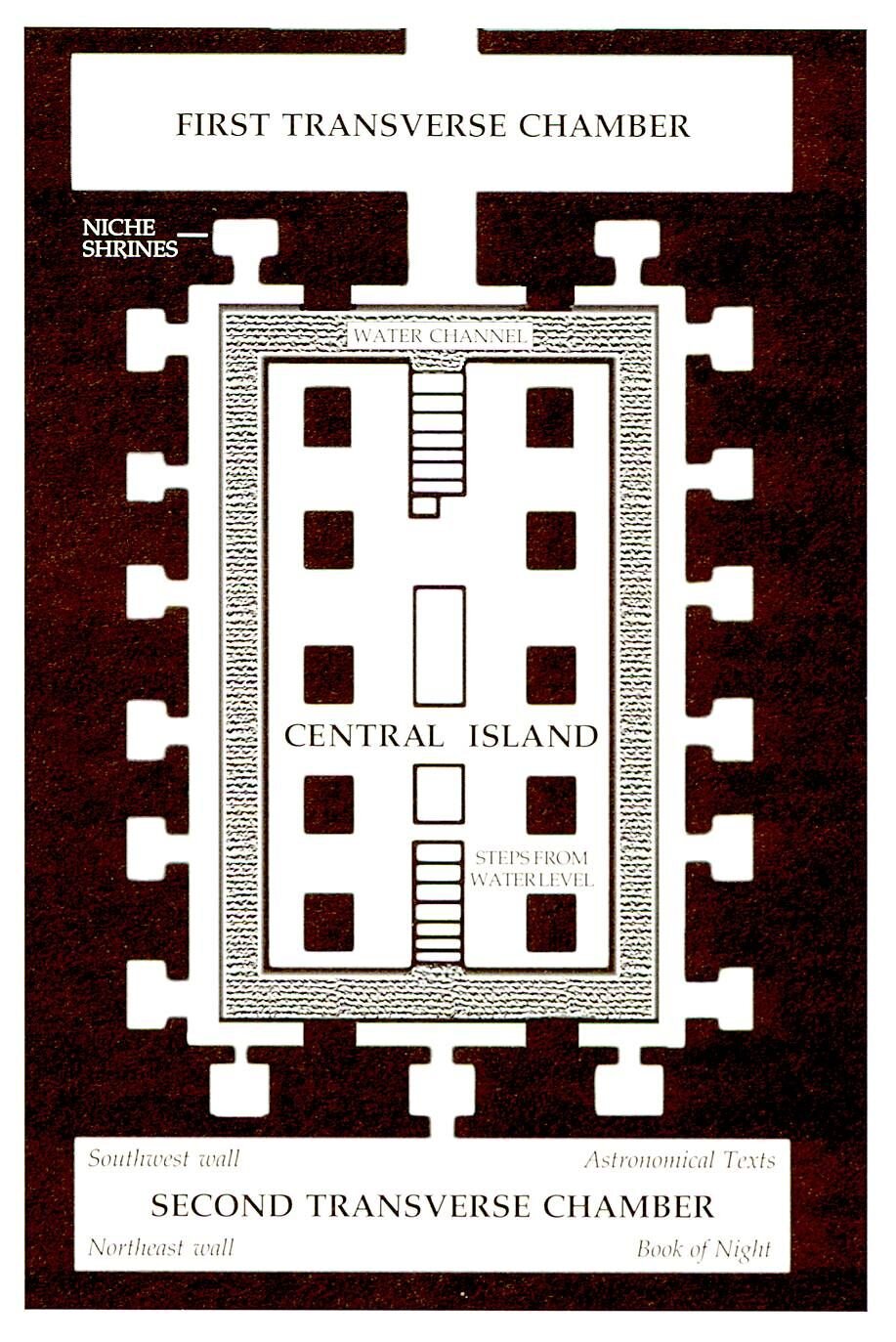

Archaeologists uncovered what is believed to be the remains of a "lost labyrinth" below the sand of a famous pyramid site, in what was previously thought to be a mythical structure. Known also as the Labyrinth, the Pyramid of Hawara (built by Amenemhet III) was the most visited sites of the ancient World. Herodotus claimed to have counted three thousand rooms in the pyramids funeral complex during the 5th century BC.

There are many discoveries beneath the surface of our planet which could potentially change the way we look at history itself. One of them is a forgotten world of underground chambers and tunnels that have remained unexplored for centuries. Mentioned in ancient texts and local legends, these mysterious chambers have been considered as a myth up until they were actually discovered.

The ‘Lost Labyrinth of Egypt’ is without a doubt one of those incredible ancient sites that are a lost jewel in today’s history.

This I have actually seen, a work beyond words. For if anyone put together the buildings of the Greeks and display of their labours, they would seem lesser in both effort and expense to this labyrinth… Even the pyramids are beyond words, and each was equal to many and mighty works of the Greeks. Yet the labyrinth surpasses even the pyramids. Herodotus (‘Histories’, Book, II, 148),

This mysterious underground complex of caverns and chambers was described by authors such as Strabo and even Herodotus who had the opportunity to visit and record the legendary labyrinth before it disappeared into history. According to writing by Herodotus I the IV century BC: the labyrinth was “situated a little above the lake of Moiris and nearly opposite to that which is called the City of Crocodiles” (‘Histories,’ Book, II, 148).

The labyrinth (as it has been called by some in the distant past) is said to be an extraordinary underground complex which could hold the key to mankind’s history. It is said that there, we could find details about unknown civilizations in history, great empires, and rulers that lived on the planet before history as we know it began.

“When one had entered the sacred enclosure, one found a temple surrounded by columns, 40 to each side, and this building had a roof made of a single stone, carved with panels and richly adorned with excellent paintings. It contained memorials of the homeland of each of the kings as well as of the temples and sacrifices carried out in it, all skilfully worked in paintings of the greatest beauty.”

Based on the descriptions of ancient texts such as those from Herodotus, and others who visited the magical labyrinth in the distant past, a 17th century German Jesuit scholar called Athanasius Kircher, created the first pictorial reproduction of the enigmatic labyrinth just as Herodotus described it: “It has twelve courts covered in, with gates facing one another, six upon the North side and six upon the South, joining on one to another, and the same wall surrounds them all outside; and there are in it two kinds of chambers, the one kind below the ground and the other above upon these, three thousand in number, of each kind fifteen hundred. […]The upper set of chambers we ourselves saw, but the chambers underground we only heard about. For the passages through the chambers, and the goings this way and that way through the courts, which were admirably adorned, afforded endless matter for marvel, as we went through from a court to the chambers to colonnades, and from the colonnades to other rooms, and then from the chambers again to other courts. […]Over the whole of these is roof made of stone like the walls; and the walls are covered with figures craved upon them, each court being surrounded with pillars of white stone fitted together most perfectly; and at the end of the labyrinth, by the corner of it, there is a pyramid of fourty fathoms, upon which large figures are carved, and to this there is a way made under ground. Such is this labyrinth.”

Reconstruction of the Egyptian Labyrinth by Athanasius Kircher (copper-plate engraving) 1670.

According to these authors, the underground temple consists of over 3000 rooms which are filled with incredible hieroglyphs and paintings, the enigmatic underground complex is located less than 100 kilometers from Cairo at Hawara. There, in 2008 a group of researchers from Belgium and Egypt arrived to investigate the enigmatic underground complex, with the aid of ground penetrating technology which was used to study the sand in hopes of finding and solving the mystery behind the mysterious underground complex. The Belgian-Egyptian expedition was able to confirm the presence of the underground temple not far from the Pyramid of Amenemhat III.

Possible location of the tunnels.

With no visible remains, the story was thought to simply be a legend passed down by generations until Egyptologist Flinders Petrie uncovered its “foundations” in the 1800s, leading experts to theories the labyrinth was demolished under the reign of Ptolemy II, and used to build the nearby city of Shedyt to honour his wife Arsinoe. Without a doubt, the expedition led by Petrie stumbled upon one of the most incredible discoveries in the history of Egypt, and they did not even need to excavate in order to confirm the finding.

But, in 2008, archaeologists working on the Mataha Expedition made a stunning find below the sands, researcher Ben Van Kerkwyk revealed on his YouTube channel ‘UnchartedX’. The results of the expedition ere published in 2008, shortly after the discovery in the scientific journal of the NRIAG and the results of the research were exchanged in a public lecture at the University of Ghent, which Media from Belgium attended. But the finding was quickly suppressed since the Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (Egypt) put a hold to all further communications about the discovery due to Egyptian National Security sanctions.

Mr Van Kerkwyk went on to detail what the area may have looked like some 2,000 years ago.

He added: “Unknown until 12 years ago, the discovery was suppressed and today the incredible potential of this site is being slowly and irrevocably destroyed by both inaction by authorities and by the water table in the area that’s rising. Compared with Giza, or any of the other well-known ancient Egyptian sites, there really isn’t a lot to immediately take in.”

Mr Van Kerkwyk detailed how Mr Petrie first stumbled across the find.

He added: “Some fragments of once-mighty granite columns carved in palm or lotus shapes along with other small fragments of ancient stonework are left lying in a small, open-air museum. The site is dominated by the remains of the pyramid of Amenemhat III with only the mud-brick internal structure remaining to see. The remains of the labyrinth have been discovered in the sandy areas to the south of the pyramid. The first to find any real evidence of this was the great Flinders Petrie, who, in the late 1800s, discovered the remains of a huge stone foundation, more than 300 metres broad around four metres beneath the sand. He concluded that this was the remnants of the foundations for the labyrinth, with the structure itself being long since quarried and destroyed.”

Archaeologists found evidence of a huge structure hiding below the sand in 2008, but Mr Van Kerkwyk said the area has never been excavated. He continued: “However, new evidence collected in modern times is challenging his conclusion and it now seems likely that what Petrie found was not the foundation, but instead was part of the ceiling or roof. These same areas were scanned in 2008, using ground-penetrating radar, by the Mataha Expedition, a collaboration between Egyptian authorities, the Ghent University of Belgium and funded by contemporary artist Louis De Cordier. The results of this expedition clearly indicate the presence of grid-like and ordered structures deep beneath the sand in levels much deeper than Petrie ever excavated. Although this expedition was conducted with the full cooperation and permission of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, the official results and conclusion of this legitimate scientific study have never been released.”

The Pyramid of the 12th Dynasty Pharaoh Amenemhat III at Hawara.

Louis de Cordier, the lead researchers of the expedition waited patiently for two years for the Supreme Council to acknowledge the findings and make them public, regrettably, it never happened. In 2010, de Cordier opened a website in order to make the discovery available to the entire world. Even though researchers have confirmed the existence of the underground complex, mayor excavations need to take place in the future in order to explore the incredible finding. It is believed that the treasures of the underground Labyrinth could hold the answers to countless historic mysteries and the ancient Egyptian civilization.

Source: Ancient Code Team, CALLUM HOARE

Official website of the expedition: labyrinthofegypt.com

Ancient Origins: The Lost Labyrinth of Ancient Egypt

You can download the report of GEOPHYSICAL STUDIES OF HAWARA PYRAMID AREA-Faiyum by the National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics HERE.

You can find out more by visiting the website or Facebook Page of the Labyrinth of Egypt

Evidence of Oldest Gynaecological Treatment on Record, Performed in Ancient Egypt 4,000 Years Ago

Scientists from the Universities of Granada and Jaén are studying the physical evidence found in the mummified remains of a woman who suffered severe trauma to the pelvis in 1878–1797 BC, linking them to a medical treatment described in various Egyptian medical papyri of the time

During the Qubbet el-Hawa Project, led by the University of Jaén (UJA) in Aswan (Egypt), in which scientists from the University of Granada (UGR) are participating, researchers have found evidence of the oldest gynaecological treatment on record, performed on a woman who lived in Ancient Egypt some 4,000 years ago and died in 1878–1797 BC.

During the 2017 archaeological dig organised in Qubbet el-Hawa, on the western bank of the River Nile, Andalusian researchers found a vertical shaft dug into the rock in tomb QH34, leading to a burial chamber with ten intact skeletons.